Related Research Articles

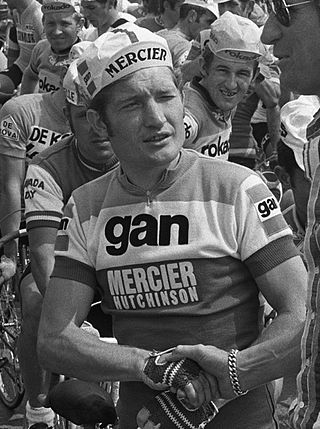

Bernard Thévenet is a retired professional cyclist. His sporting career began with ACBB Paris. He is a two-time winner of the Tour de France and known for ending the reign of five-time Tour champion Eddy Merckx, though both feats are tarnished by Thévenet's later admission of steroids use during his career. He also won the Dauphiné Libéré in 1975 and 1976.

Richard Virenque is a retired French professional road racing cyclist. He was one of the most popular French riders with fans for his boyish personality and his long, lone attacks. He was a climber, best remembered for winning the King of the Mountains competition of the Tour de France a record seven times, but he is best known from the general French public as one of the central figures in a widespread doping scandal in 1998, the Festina Affair, and for repeatedly denying his involvement despite damning evidence.

Laurent Jalabert is a French former professional road racing cyclist, from 1989 to 2002.

Cyrille Guimard is a French former professional road racing cyclist who became a directeur sportif and television commentator. Three of his riders, Bernard Hinault, Laurent Fignon, and Lucien Van Impe, won the Tour de France. Another of his protégés, Greg LeMond, described him as "the best (coach) in the world" and "the best coach I ever had". He has been described by cycling journalist William Fotheringham as the greatest directeur sportif in the history of the Tour.

Freddy Maertens is a Belgian former professional racing cyclist who was twice world road race champion. His career coincided with the best years of another Belgian rider, Eddy Merckx, and supporters and reporters were split over who was better. Maertens' career swung between winning more than 50 races in a season to winning almost none and then back again. His life has been marked by debt and alcoholism. It took him more than two decades to pay a tax debt. At one point early in his career, between the 1976 Tour and 1977 Giro, Maertens won 28 out of 60 Grand Tour stages that he entered before abandoning the Giro due to injury on stage 8b. Eight Tour stage wins, thirteen Vuelta stage wins and seven Giro stage wins in less than one calendar year.

Christophe Bassons is a French former professional road racing cyclist. His career ended when he spoke out about doping in the Tour de France.

Jean Robic was a French road racing cyclist who won the 1947 Tour de France. Robic was a professional cyclist from 1943 to 1961. His diminutive stature and appearance was encapsulated in his nickname Biquet(Kid goat). For faster, gravity-assisted descents, he collected drinking bottles ballasted with lead or mercury at the summits of mountain climbs and "cols". After fracturing his skull in 1944 he always wore a trademark leather crash helmet.

There have been allegations of doping in the Tour de France since the race began in 1903. Early Tour riders consumed alcohol and used ether, among other substances, as a means of dulling the pain of competing in endurance cycling. Riders began using substances as a means of increasing performance rather than dulling the senses, and organizing bodies such as the Tour and the International Cycling Union (UCI), as well as government bodies, enacted policies to combat the practice.

Raphaël Géminiani was a French road bicycle racer. He had three podium finishes in the Grand Tours. He was one of four children of Italian immigrants who moved to Clermont-Ferrand fleeing from fascist violence. He worked in a cycle shop and started racing as a boy. He became a professional and then a directeur sportif, notably of Jacques Anquetil and the St-Raphaël team.

Florent Brard is a retired French road bicycle racer. He won three national championships, including the professional road race. He became a professional in 1999 and stopped racing in November 2009 after not finding a place in a team.

The Festina affair was a series of doping scandals within the sport of professional cycling that occurred during and after the 1998 Tour de France. The affair began when a large haul of doping products was found in a support car belonging to the Festina cycling team just before the start of the race. A resulting investigation revealed systematic doping involving many teams in the Tour de France. Hotels where teams were staying were raided and searched by police, confessions were made by several retired and current riders, and team personnel were arrested or detained. Several teams withdrew completely from the race.

Raymond Delisle was a French professional road bicycle racer. His sporting career began with ACBB Paris. He is the only rider to have won a stage of the Tour de France on 14 July, France's national day, while wearing the jersey of national champion.

Eric Rijkaert also written Eric Rijckaert was born in Oostwinkel, Belgium. He was a former Belgian sports physician and worked with the Festina cycling team. He was said to be at the heart of the Festina affair of 1998 that led to the withdrawal of the entire Festina team during the 1998 Tour de France. Rijkaert was the team doctor from 1993 until the Festina affair in 1998.

Gewiss–Ballan was an Italian-based road bicycle racing team active from 1993 to 1997, named after the Italian electrical engineering company Gewiss. The team was successful in the Giro d'Italia and the Tour de France as well as several classics during the early 1990s.

Alan Ramsbottom was a professional racing cyclist from Clayton-le-Moors, England, who twice rode the Tour de France.

Pierre Dumas was a French doctor who pioneered drug tests in the Olympic Games and cycling. He was doctor of the Tour de France from 1952 to 1969 and head of drug-testing at race until 1977.

Bernard Sainz, a.k.a. Dr Mabuse, is an unlicensed sports doctor who achieved great success in horse racing and cycling. He was jailed for falsely practising medicine, particularly in cycle racing, and received other sentences for doping-related charges, which he consistently denied.

Maurice De Muer was a French cyclist who rode as a professional between 1943 and 1951 and later became a cycling team manager.

The year in which the 1998 Tour de France took place marked the moment when cycling was fundamentally shattered by doping revelations. Paradoxically no riders were caught failing drug tests by any of the ordinary doping controls in place at the time. Nevertheless, several police searches and interrogations managed to prove existence of organized doping at the two teams Festina and TVM, who consequently had to withdraw from the race. After stage 16, the police also forced the virtual mountain jersey holder Rodolfo Massi to leave the race, due to having found illegal corticosteroids in his hotel room. The intensive police work then led to a peloton strike at stage 17, with a fallout of four Spanish teams and one Italian team deciding to leave the race in protest.

References

- ↑ "Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré :: Fiche de Rachel DARD". criterium.ledauphine.com. Archived from the original on 2008-06-09.

- ↑ "www.cyclingnews.com – the world centre of cycling". autobus.cyclingnews.com.

- ↑ Livre d'Or 1973/74. Paris: Miroir du Cyclisme. 1974. p. 44.

- 1 2 Wielerrevue, the Netherlands, De Koerier van Dax, undated cutting

- 1 2 3 France Soir, 1 October 1976

- ↑ L'Équipe, 22 November 1976

- ↑ de Mondenard, Jean-Pierre, Dictionnaire du Dopage, Masson, France

- 1 2 "Le portrait de François Bellocq". www.cyclisme-dopage.com.

- ↑ de Mondenard, J-P and Chévalier, B. (1981) Le Dossier Noir de Dopage, Hachette, France