Related Research Articles

Mutualism describes the ecological interaction between two or more species where each species has a net benefit. Mutualism is a common type of ecological interaction. Prominent examples are:

Domestication is a multi-generational mutualistic relationship in which an animal species, such as humans or leafcutter ants, takes over control and care of another species, such as sheep or fungi, to obtain from them a steady supply of resources, such as meat, milk, or labor. The process is gradual and geographically diffuse, based on trial and error. Domestication affected genes for behavior in animals, making them less aggressive. In plants, domestication affected genes for morphology, such as increasing seed size and stopping the shattering of cereal seedheads. Such changes both make domesticated organisms easier to handle and reduce their ability to survive in the wild.

In population genetics, gene flow is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent allele frequencies and therefore can be considered a single effective population. It has been shown that it takes only "one migrant per generation" to prevent populations from diverging due to drift. Populations can diverge due to selection even when they are exchanging alleles, if the selection pressure is strong enough. Gene flow is an important mechanism for transferring genetic diversity among populations. Migrants change the distribution of genetic diversity among populations, by modifying allele frequencies. High rates of gene flow can reduce the genetic differentiation between the two groups, increasing homogeneity. For this reason, gene flow has been thought to constrain speciation and prevent range expansion by combining the gene pools of the groups, thus preventing the development of differences in genetic variation that would have led to differentiation and adaptation. In some cases dispersal resulting in gene flow may also result in the addition of novel genetic variants under positive selection to the gene pool of a species or population

A frugivore is an animal that thrives mostly on raw fruits or succulent fruit-like produce of plants such as roots, shoots, nuts and seeds. Approximately 20% of mammalian herbivores eat fruit. Frugivores are highly dependent on the abundance and nutritional composition of fruits. Frugivores can benefit or hinder fruit-producing plants by either dispersing or destroying their seeds through digestion. When both the fruit-producing plant and the frugivore benefit by fruit-eating behavior the interaction is a form of mutualism.

Biological dispersal refers to both the movement of individuals from their birth site to their breeding site and the movement from one breeding site to another . Dispersal is also used to describe the movement of propagules such as seeds and spores. Technically, dispersal is defined as any movement that has the potential to lead to gene flow. The act of dispersal involves three phases: departure, transfer, and settlement. There are different fitness costs and benefits associated with each of these phases. Through simply moving from one habitat patch to another, the dispersal of an individual has consequences not only for individual fitness, but also for population dynamics, population genetics, and species distribution. Understanding dispersal and the consequences, both for evolutionary strategies at a species level and for processes at an ecosystem level, requires understanding on the type of dispersal, the dispersal range of a given species, and the dispersal mechanisms involved. Biological dispersal can be correlated to population density. The range of variations of a species' location determines the expansion range.

In spermatophyte plants, seed dispersal is the movement, spread or transport of seeds away from the parent plant. Plants have limited mobility and rely upon a variety of dispersal vectors to transport their seeds, including both abiotic vectors, such as the wind, and living (biotic) vectors such as birds. Seeds can be dispersed away from the parent plant individually or collectively, as well as dispersed in both space and time.

Myrmecochory ( ; from Ancient Greek: μύρμηξ, romanized: mýrmēks and χορεία khoreíā is seed dispersal by ants, an ecologically significant ant–plant interaction with worldwide distribution. Most myrmecochorous plants produce seeds with elaiosomes, a term encompassing various external appendages or "food bodies" rich in lipids, amino acids, or other nutrients that are attractive to ants. The seed with its attached elaiosome is collectively known as a diaspore. Seed dispersal by ants is typically accomplished when foraging workers carry diaspores back to the ant colony, after which the elaiosome is removed or fed directly to ant larvae. Once the elaiosome is consumed, the seed is usually discarded in an underground midden or ejected from the nest. Although diaspores are seldom distributed far from the parent plant, myrmecochores also benefit from this predominantly mutualistic interaction through dispersal to favourable locations for germination, as well as escape from seed predation.

A dispersal vector is an agent of biological dispersal that moves a dispersal unit, or organism, away from its birth population to another location or population in which the individual will reproduce. These dispersal units can range from pollen to seeds to fungi to entire organisms.

Gene Ezia Robinson is an American entomologist, Director of the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology and National Academy of Sciences member. He pioneered the application of genomics to the study of social behavior and led the effort to sequence the honey bee genome. On February 10, 2009, his research was famously featured in an episode of The Colbert Report whose eponymous host referred to the honey Dr. Robinson sent him as "pharmaceutical-grade hive jive".

The Agricultural Research Organization, Volcani Institute, previously known as the Agricultural Research Station of the Jewish Agency for Israel, is an Israeli agricultural research center. It serves as the research arm of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of the State of Israel and provides research opportunities for local and international scientists at post-graduate levels, as well as educational opportunities for Israeli and international youths, farmers and scientists. The organization supports Israeli agriculture research, focusing on plant sciences, animal sciences, plant protection, soil and environmental sciences, food sciences, and agricultural engineering. The organization was founded in 1921 in Ben Shemen, Israel, by Yitzhak Elazari Volcani, for whom it is named.

Seed dispersal syndromes are morphological characters of seeds correlated to particular seed dispersal agents. Dispersal is the event by which individuals move from the site of their parents to establish in a new area. A seed disperser is the vector by which a seed moves from its parent to the resting place where the individual will establish, for instance an animal. Similar to the term syndrome, a diaspore is a morphological functional unit of a seed for dispersal purposes.

Henry S. Horn was a natural historian and ecologist. He was an emeritus professor in the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Department at Princeton University. He worked on a wide variety of topics including the following:

Shimon Schuldiner is an Israeli biochemist. He has made important contributions to the understanding of proteins that couple the movement of ions and other molecules across membranes. Schuldiner is Mathilda Marks-Kennedy Professor at the Alexander Silberman Institute of Life Sciences, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He received a B.Sc. in 1967 and an M.Sc. in 1968 from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and a Ph.D. from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot in 1973.

Diplochory, also known as “secondary dispersal”, “indirect dispersal” or "two-phase dispersal", is a seed dispersal mechanism in which a plant's seed is moved sequentially by more than one dispersal mechanism or vector. The significance of the multiple dispersal steps on the plant fitness and population dynamics depends on the type of dispersers involved. In many cases, secondary seed dispersal by invertebrates or rodents moves seeds over a relatively short distance and a large proportion of the seeds may be lost to seed predation within this step. Longer dispersal distances and potentially larger ecological consequences follow from sequential endochory by two different animals, i.e. diploendozoochory: a primary disperser that initially consumes the seed, and a secondary, carnivorous animal that kills and eats the primary consumer along with the seeds in the prey's digestive tract, and then transports the seed further in its own digestive tract.

Migration, in ecology, is the large-scale movement of members of a species to a different environment. Migration is a natural behavior and component of the life cycle of many species of mobile organisms, not limited to animals, though animal migration is the best known type. Migration is often cyclical, frequently occurring on a seasonal basis, and in some cases on a daily basis. Species migrate to take advantage of more favorable conditions with respect to food availability, safety from predation, mating opportunity, or other environmental factors.

Michal Linial is a Professor of Biochemistry and Bioinformatics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI). Linial is the Director of The Sudarsky Center for Computational Biology at HUJI. Since 2015, she is head of the ELIXIR-Israel node.

Pedro Diego Jordano Barbudo is an ecologist, conservationist, researcher, focused on evolutionary ecology and ecological interactions. He is an honorary professor and associate professor at University of Sevilla, Spain. Most of his fieldwork is done in Parque Natural de las Sierras de Cazorla, Segura y Las Villas, in the eastern side of Andalucia, and in Doñana National Park, where he holds the title of Research Professor for the Estación Biológica Doñana, Spanish Council for Scientific Research (CSIC). Since 2000 he has been actively doing research in Brazil, with fieldwork in the SE Atlantic rainforest.

Erella Hovers is an Israeli paleoanthropologist. She is currently a professor at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, working within the Institute of Archeology. The majority of her field work is centered in the Horn of Africa, with a primary focus on Ein Qashish, Israel and Eastern Ethiopia. Her research concentrates on the development of the use of symbolism during the Levantine Middle Palaeolithic and Middle Stone Age. Other research interests include lithic technology, taphonomy, and general behavior of early hominids.

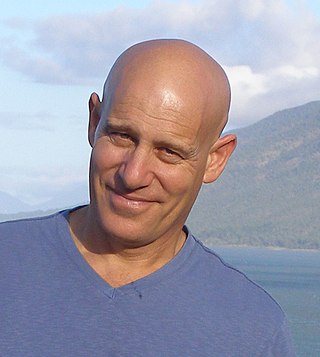

Guy Bloch is an Israeli scientist. He is a professor at the Alexander Silberman Institute of Life Sciences, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His research focuses on the evolution and the molecular and physiological basis of social behavior and sociality in bees.

Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Brain Sciences(ELSC) (Hebrew: מרכז אדמונד ולילי ספרא למדעי המוח) is a brain science research center affiliated with Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The director of the center is Israel Nelken.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Minerva Center for Movement Ecology

- ↑ Ran Nathan, Dept. of Ecology, Evolution & Behavior

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The Division for Advancement and External Relations, HUJI

- ↑ The Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, HUJI

- 1 2 Movement Ecology Lab website

- 1 2 Movement Ecology Journal Editorial Board

- 1 2 Mechanisms of long-distance dispersal of seeds by wind, Nature, 2002

- 1 2 Nathan, Ran; Muller-Landau, Helene C. (2000). "Spatial patterns of seed dispersal, their determinants and consequences for recruitment". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 15 (7): 278–285. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01874-7. PMID 10856948.

- 1 2 Nathan, Ran; Schurr, Frank M.; Spiegel, Orr; Steinitz, Ofer; Trakhtenbrot, Ana; Tsoar, Asaf (2008). "Mechanisms of long-distance seed dispersal". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 23 (11): 638–647. Bibcode:2008TEcoE..23..638N. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.08.003. PMID 18823680.

- 1 2 Nathan, Ran (2011). "Spread of North American wind-dispersed trees in future environments". Ecology Letters. 14 (3): 211–219. Bibcode:2011EcolL..14..211N. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.459.2341 . doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01573.x. PMID 21251175.

- ↑ Ran Nathan on the Growing Importance of Movement Ecology, Science Watch

- ↑ Israeli Institute for Advanced Studies in Jerusalem

- ↑ Movement Ecology Special Feature, PNAS, 2008

- ↑ Proceedings of the National Academy of USA

- 1 2 A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research, PNAS, 2008

- ↑ An emerging movement ecology paradigm, PNAS, 2008

- ↑ Minerva Foundation

- ↑ Sivan Toledo, TAU

- ↑ The ATLAS project

- ↑ Flying with the birds, Deutsche Welle

- ↑ Movement Ecology Journal website

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Asian Science Camp program, 2012

- ↑ Ecological Expert Chosen to Receive HU’s President’s Prize for Outstanding Young Researcher

- ↑ Israeli prize winner rides the wave of movement ecology

- ↑ News Release of HUJI, HU Researcher wins Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel Award

- ↑ The Australian Friends of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem talk - An Emerging Movement Ecology Paradigm

- ↑ Long-distance dispersal of plants, Science, 2006

- ↑ Large-scale navigational map in a mammal, PNAS, 2011

- ↑ Using tri-axial acceleration data to identify behavioral modes of free-ranging animals: general concepts and tools illustrated for Griffon Vultures, Journal of Experimental Biology, 2012

- ↑ Horvitz, Nir (2014). "The gliding speed of migrating birds: slow and safe or fast and risky?". Ecology Letters. 17 (6): 670–679. Bibcode:2014EcolL..17..670H. doi:10.1111/ele.12268. PMID 24641086.

- ↑ Shohami, D. (2013). "Fire-induced population reduction and landscape opening increases gene flow via pollen dispersal inPinus halepensis". Molecular Ecology. 23 (1): 70–81. doi:10.1111/mec.12506. PMID 24128259. S2CID 24814215.