The Great Disappointment in the Millerite movement was the reaction that followed Baptist preacher William Miller's proclamation that Jesus Christ would return to the Earth by 1844, which he called the Second Advent. His study of the Daniel 8 prophecy during the Second Great Awakening led him to conclude that Daniel's "cleansing of the sanctuary" was cleansing the world from sin when Christ would come, and he and many others prepared. When Jesus did not appear by October 22, 1844, Miller and his followers were disappointed.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church had its roots in the Millerite movement of the 1830s to the 1840s, during the period of the Second Great Awakening, and was officially founded in 1863. Prominent figures in the early church included Hiram Edson, Ellen G. White, her husband James Springer White, Joseph Bates, and J. N. Andrews. Over the ensuing decades the church expanded from its original base in New England to become an international organization. Significant developments such the reviews initiated by evangelicals Donald Barnhouse and Walter Martin, in the 20th century led to its recognition as a Christian denomination.

Criticism of the Seventh-day Adventist Church includes observations made about its teachings, structure, and practices or theological disagreements from various individuals and groups.

Last Generation Theology (LGT) or "final generation" theology is a religious belief regarding moral perfection achieved by sanctified people in the last generation before the Second Coming of Jesus. It was a concept that had its origins in the beliefs and teachings of Seventh-day Adventist Church pioneers, and there are verses in scripture in texts such as 2 Corinthians 7:1, Matthew 5:48, and many others. Seventh-day Adventists hold that there will be an end-time remnant of believers who are faithful to God, which will be manifest shortly prior to the second coming of Jesus, as suggested by the 144,000 saints described in the Book of Revelation of the New Testament.

In Seventh-day Adventist theology, the Great Controversy theme refers to the cosmic battle between Jesus Christ and Satan, also played out on earth. Ellen G. White, a member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, who wrote several books explaining, but allegedly never disagreeing with the Bible, delineates the theme in her book The Great Controversy, first published in 1858. The concept, or metanarrative, derives from many visions the author reported to have received, as well as from scriptural references. Adventist theology sees the concept as important in that it provides an understanding of the origin of evil, and of the eventual destruction of evil and the restoration of God's original purpose for this world. It constitutes belief number 8 of the church's 28 Fundamentals.

The investigative judgment, or pre-Advent Judgment, is a unique Seventh-day Adventist doctrine, which asserts that the divine judgment of professed Christians has been in progress since 1844. It is intimately related to the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church and was described by one of the church's pioneers Ellen G. White as one of the pillars of Adventist belief. It is a major component of the broader Adventist understanding of the "heavenly sanctuary", and the two are sometimes spoken of interchangeably.

The remnant is a recurring theme throughout the Hebrew and Christian Bible. The Anchor Bible Dictionary describes it as "What is left of a community after it undergoes a catastrophe". The concept has stronger representation in the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament than in the Christian New Testament.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church holds a unique system of eschatological beliefs. Adventist eschatology, which is based on a historicist interpretation of prophecy, is characterised principally by the premillennial Second Coming of Christ. Traditionally, the church has taught that the Second Coming will be preceded by a global crisis with the Sabbath as a central issue. At Jesus' return, the righteous will be taken to heaven for one thousand years. After the millennium the unsaved cease to exist as they will be punished by annihilation while the saved will live on a recreated Earth for eternity.

The theology of the Seventh-day Adventist Church resembles early Protestant Christianity, combining elements from Lutheran, Wesleyan-Arminian, and Anabaptist branches of Protestantism. Adventists believe in the infallibility of the Scripture's teaching regarding salvation, which comes from grace through faith in Jesus Christ. The 28 fundamental beliefs constitute the church's current doctrinal positions, but they are revisable under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, and are not a creed.

The 1888 Minneapolis General Conference Session was a meeting of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists held in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in October 1888. It is regarded as a landmark event in the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Key participants were Alonzo T. Jones and Ellet J. Waggoner, who presented a message on justification supported by Ellen G. White, but resisted by leaders such as G. I. Butler, Uriah Smith and others. The session discussed crucial theological issues such as the meaning of "righteousness by faith", the nature of the Godhead, the relationship between law and grace, and Justification and its relationship to Sanctification.

Seventh-day Adventists Answer Questions on Doctrine is a book published by the Seventh-day Adventist Church in 1957 to help explain Adventism to conservative Protestants and Evangelicals. The book generated greater acceptance of the Adventist church within the evangelical community, where it had previously been widely regarded as a cult. However, it also proved to be one of the most controversial publications in Adventist history and the release of the book brought prolonged alienation and separation within Adventism and evangelicalism.

Milian Lauritz Andreasen, was a Seventh-day Adventist theologian, pastor and author.

The "three angels' messages" is an interpretation of the messages given by three angels in Revelation 14:6–12. The Seventh-day Adventist church teaches that these messages are given to prepare the world for the second coming of Jesus Christ, and sees them as a central part of its own mission.

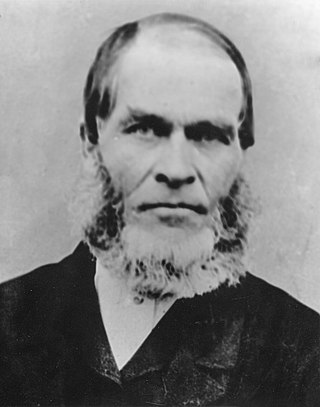

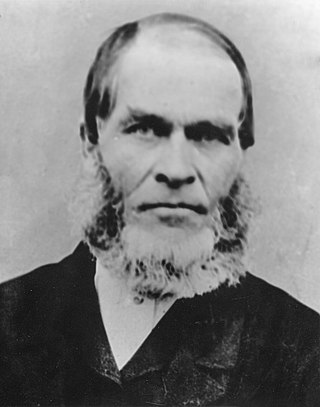

Hiram Edson (1806–1882) was a pioneer of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, known for introducing the sanctuary doctrine to the church. Hiram Edson was a Millerite adventist, and became a Sabbath-keeping Adventist. Like all Millerites, Edson expected that the Second Coming of Jesus Christ would occur on October 22, 1844. This belief was based on an interpretation of the 2300 day prophecy which predicted that "the sanctuary would be cleansed" which Millerites took to mean that Christ would return on that day.

In Seventh-day Adventist theology, the heavenly sanctuary teaching asserts that many aspects of the Hebrew tabernacle or sanctuary are representative of heavenly realities. In particular, Jesus is regarded as the High Priest who provides atonement for human sins by the sacrificial shedding of his blood at Calvary. The doctrine is based on Hebrews 4:14-15. As a whole, it is unique to Seventh-day Adventism, although other denominations share many of the typological identifications made by the epistle to the Hebrews, see Hebrews 8:2. One major aspect which is completely unique to Adventism is that the day of atonement is a type or foreshadowing of the investigative judgment. Technically, the "heavenly sanctuary" is an umbrella term which includes the investigative judgment, Christ's ministry in heaven before then, the understanding of Daniel 8:14, etc. However, it is often spoken of interchangeably with the investigative judgment.

Ángel Manuel Rodríguez (1945—) is a Seventh-day Adventist theologian and was the director of the Biblical Research Institute (BRI) before his retirement. His special research interests include Old Testament, Sanctuary and Atonement, and Old Testament Theology. He has written several books, and authors a monthly column in Adventist World.

Interpretations of the law in the Bible within the Seventh-day Adventist Church form a part of the broader debate regarding biblical law in Christianity. Adventists believe in a greater continuation of laws such as the law given to Moses in the present day than do most other Christians. In particular, they believe the 10 Commandments still apply to today, including the Sabbath in particular.

Hans Karl LaRondelle was a respected Seventh-day Adventist theologian; a strong proponent of the gospel and salvation by faith alone. In a 1985 questionnaire of North American Adventist Theology lecturers, LaRondelle tied for fourth place among the Adventist authors who had most influenced them, and was number one amongst the under 39 age group. He died March 7, 2011.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church pioneers were members of Seventh-day Adventist Church, part of the group of Millerites who came together after the Great Disappointment across the United States and formed the Seventh-day Adventist Church. In 1860, the pioneers of the fledgling movement settled on the name, Seventh-day Adventist, representative of the church's distinguishing beliefs. Three years later, on May 21, 1863, the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists was formed and the movement became an official organization.

The Pillars of Adventism are landmark doctrines for Seventh-day Adventists. They are Bible doctrines that define who they are as a people of faith; doctrines that are "non-negotiables" in Adventist theology. The Seventh-day Adventist church teaches that these Pillars are needed to prepare the world for the second coming of Jesus Christ, and sees them as a central part of its own mission. Adventists teach that the Seventh-day Adventist Church doctrines were both a continuation of the reformation started in the 16th century and a movement of the end time rising from the Millerites, bringing God's final messages and warnings to the world.