Related Research Articles

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the International Criminal Court. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, such as schools and hospitals by people of different races. Specifically, it may be applied to activities such as eating in restaurants, drinking from water fountains, using public toilets, attending schools, going to films, riding buses, renting or purchasing homes or renting hotel rooms. In addition, segregation often allows close contact between members of different racial or ethnic groups in hierarchical situations, such as allowing a person of one race to work as a servant for a member of another race.

Economic, social and cultural rights, (ESCR) are socio-economic human rights, such as the right to education, right to housing, right to an adequate standard of living, right to health, victims' rights and the right to science and culture. Economic, social and cultural rights are recognised and protected in international and regional human rights instruments. Member states have a legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfil economic, social and cultural rights and are expected to take "progressive action" towards their fulfilment.

Bulgaria joined the European Union in 2007, its compliance with human rights norms, however, is far from perfect. Although the media have a record of unbiased reporting, Bulgaria’s lack of specific legislation protecting the media from state interference is a theoretical weakness. Conditions in Bulgaria’s twelve aging and overcrowded prisons generally are poor. A probate reform in mid-2005 was expected to relieve prison overcrowding.

Human rights in Romania are generally respected by the government. However, there have been concerns regarding allegations of police brutality, mistreatment of the Romani minority, government corruption, poor prison conditions, and compromised judicial independence. Romania was ranked 59th out of 167 countries in the 2015 Democracy Index and is described as a "flawed democracy", similar to other countries in Central or Eastern Europe.

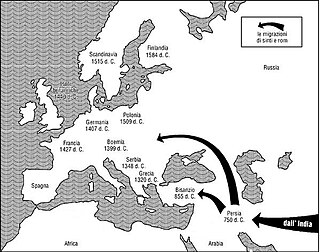

Anti-Romani sentiment is a form of anti-Indian sentiment which consists of hostility, prejudice, discrimination, racism and xenophobia which is specifically directed at Romani people. Non-Romani itinerant groups in Europe such as the Yenish, Irish and Highland Travellers are often given the name "gypsy" and confused with the Romani people. As a result, sentiments which were originally directed at the Romani people are also directed at other traveler groups and they are often referred to as "antigypsy" sentiments.

Barbora Bukovská is a Czech-Slovak human rights attorney and activist, known for her work on racial discrimination of Romani people in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Before anti-discrimination laws were adopted, she initiated the first Czech strategic litigation cases concerning discrimination against Romani people in access to public services, housing, employment and within the criminal justice system, and used the courts to bring a change in the law.

Human rights in Austria are generally respected by the government; however, there were problems in some areas. There were some reports of police abuse and use of unjustified force against prisoners. Antisemitic incidents, including physical attacks, name-calling, property damage, and threatening letters, telephone calls, and Internet postings occurred during the year. There was some governmental and societal discrimination against fathers, Muslims and members of unrecognized religious groups, particularly those considered "sects". There were incidents of neo-Nazi activity, rightwing extremism, and xenophobia. Trafficking in women and children for prostitution and labor also remained a problem.

According to the last census from 2021, there were 67,179 persons counted as Romani people in Slovakia, or 1.23% of the population. However, the number of Roma is usually underreported, with estimates placing the Roma population at 7-11% of the population. Thus the actual number of Roma may be over half a million.

The Xoraxane in Bosnia and Herzegovina are the largest of the 17 national minorities in the country, although—due to the stigma attached to the label—this is often not reflected in statistics and censuses.

Human rights in Estonia are acknowledgedas being generally respected by the government. Nevertheless, there are concerns in some areas, such as detention conditions, excessive police use of force, and child abuse. Estonia has been classified as a flawed democracy, with moderate privacy and human development in Europe. Individuals are guaranteed on paper the basic rights under the constitution, legislative acts, and treaties relating to human rights ratified by the Estonian government. Estonia was ranked 4th in the world by press freedoms.

The Mental Disability Advocacy Center (MDAC) is an international human rights organisation founded in Hungary in 2002. It is headquartered in Budapest.

D.H. and Others v. the Czech Republic was a case decided by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) concerning discrimination of Romani children in the education system of the Czech Republic. It was the first case of racial segregation in education to be considered by the ECtHR. As of 2021 the case is still pending at the Committee of Ministers and has not been resolved by the Czech authorities.

Oršuš and Others v. Croatia (15766/03) was a case heard before the European Court of Human Rights, concerning activities of Roma-only classes in some schools of Croatia, which were held legal by the Constitutional Court of Croatia in 2007 by a decision no. U-III-3138/2002.

According to international observers, human rights in Belgium are generally respected and the law and the judiciary provides effective means of addressing individual instances of abuse. However, some concerns have been reported by international human rights officials over the treatment of asylum seekers, prison overcrowding and the banning of full face veils. Capital punishment in Belgium is fully abolished and a prohibition on the death penalty is included in the Constitution of Belgium. Belgium was a founding member of the European Union and the Council of Europe and a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights. Belgium has minimal issues regarding corruption and was ranked 15 out of 167 countries surveyed in Transparency International's 2015 Corruption Perceptions Index.

The Roma Education Fund (REF) is a non-governmental organization established within the framework of the Decade of Roma Inclusion by Open Society Foundations and the World Bank in 2005. The organization's goal is to reduce the educational achievement gap between Roma and non-Roma in Europe through the provision of scholarships to Roma students, supporting the development of quality education, and supporting the removal of segregation of Roma students.

A Roma wall or Gypsy wall is a wall built by local authorities in the Czech Republic, Romania and Slovakia to segregate the Roma minority from the rest of the population. Such practices have been criticised by both human rights organizations and the European Union, who see it as a case of racial segregation.

The Romani people, also known as the Roma, qualify as an ethnic minority group in Poland of Indo-Aryan origins. The Council of Europe regards the endonym "Roma" more appropriate when referencing the people, and "Romani" when referencing cultural characteristics. The term Cyganie is considered an exonym in Poland.

Portugal is generally considered as successful in upholding the civil liberties and protecting the human rights of its citizens. Portugal has proved to be determined in promoting and respecting human rights at an international and national level. The country's minister of Justice as of September 2018, Francisca Van Dunem, said that Portugal has had "a good track record" on human rights but violations still do persist.

Environmental racism is a form of institutional racism leading to landfills, incinerators, and hazardous waste disposal being disproportionally placed in communities of colour. Internationally, it is also associated with extractivism, which places the environmental burdens of mining, oil extraction, and industrial agriculture upon Indigenous peoples and poorer nations largely inhabited by people of colour.

References

- ↑ "Human Rights". European Union. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 "An EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies up to 2020" (PDF). Brussels, 5.4.2011 COM(2011) 173 final. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ Crowe, David (2004). A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ Douglas-Scott, Sionaidh (2011). "The EU and Human Rights after the Treaty of Lisbon". Human Rights Law Review. 11 (4): 645–682. doi:10.1093/hrlr/ngr038.

- ↑ "EU Framework" . Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ "National Roma Integration Strategies: a first step in the implementation of the EU Framework" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ↑ "Roma Integration by EU Country" . Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ↑ The Right of Roma Children to Education Position Paper. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). 2011. p. 20.

- ↑ "OHCHR | Serbia Homepage". www.ohchr.org. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ "Serbia/Kosovo". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Germany: Roma march against asylum-seeker crackdown". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ "Germany's a Dream for Serbia's Roma Returnees :: Balkan Insight". www.balkaninsight.com. 22 October 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ "Germany Expels Roma En Masse to Serbia and Montenegro - ERRC.org". www.errc.org. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ "The Universal Declaration of Human Rights". United Nations.

- ↑ "General Comments No. 7 (1997) on forced evictions". The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ "CHARTER OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "Report on Racism and Xenophobia in the Member States of the EU - (FRA 2007) Pg 88" (PDF). European Union Fundamental Rights Agency. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ "Housing conditions of Roma and housing conditions of Roma and Travellers in the European Union Comparative report" (PDF). European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). October 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "European Federation of National Organisations working with the Homeless (FEANTSA) v. France, Complaint No. 39/2006, decision on the merits of 5 December 2007, § 163" (PDF). European Committee of Social Rights. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "National court decision –Cluj Tribunal, file number -8721/117/2011" . Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "Cluj Tribunal sanctions forced eviction of Roma families and their relocation in inadequate conditions in Pata Rat" (PDF). European network of legal experts in the non-discrimination field.

- ↑ "France sends Roma Gypsies back to Romania". BBC. 20 August 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ↑ "Census: Forced evictions of migrant Roma in France" (PDF). European Roma Rights Centre. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ Lacrymo et arrestations, une expulsion de squat qui tourne mal à Lyon-Confluence, Rue89Lyon, 2 December 2013

- 1 2 "Decision on the Merits 2011 Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) v. France Complaint No. 63/2010 pg. 5-6" (PDF). European Committee Of Human Rights.

- 1 2 Cendrowicz, Leo (17 September 2010). "Sarkozy Lashes Out as Roma Row Escalates". Time. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ "Das Wohnprojekt MARO TEMM - Wohnen mit Kultur". verband duetscher sinti und roma e.V.

- ↑ "2014 Report on the implementation of the EU framework for National Roma Integration Strategies pg. 8" (PDF). European Commission - Directorate-General for Justice, European Union. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex - 32000L0043 - EN". Official Journal L 180. 19 July 2000. pp. 22–26.

- ↑ The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, "United Nations." Retrieved 5/3/14.

- ↑ International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, "Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights." Retrieved 5/2/14.

- 1 2 3 The Right of Roma Children to Education Position Paper. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). 2011

- ↑ "Lavida and Others v. Greece (application no. 7973/10)". European Court of Human Rights.

- ↑ "Press Release on Chamber Judgment Sampanis and Others v. Greece". European Court of Human Rights.

- ↑ "Failure of the authorities to integrate Roma children into the ordinary education system amounted to discrimination against them". European Court Of Human Rights.

- ↑ "Oršuš and Others v. Croatia (application no. 15766/03)". European Court of Human Rights.

- ↑ "Factsheet: Roma and Travellers" (PDF). European Court of Human Rights.

- ↑ "HUDOC - European Court of Human Rights". hudoc.echr.coe.int.

- ↑ "HUDOC - European Court of Human Rights". hudoc.echr.coe.int.

- ↑ "Tackling discrimination | European Commission" (PDF).

- ↑ "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission.