Sir John Falstaff is a fictional character who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare and is eulogised in a fourth. His significance as a fully developed character is primarily formed in the plays Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2, where he is a companion to Prince Hal, the future King Henry V of England. Falstaff is also featured as the buffoonish suitor of two married women in The Merry Wives of Windsor. Though primarily a comic figure, he embodies a depth common to Shakespeare's major characters. A fat, vain, and boastful knight, he spends most of his time drinking at the Boar's Head Inn with petty criminals, living on stolen or borrowed money. Falstaff leads the apparently wayward Prince Hal into trouble, and is repudiated when Hal becomes king.

Falstaff is a comic opera in three acts by the Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi. The Italian-language libretto was adapted by Arrigo Boito from the play The Merry Wives of Windsor and scenes from Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2, by William Shakespeare. The work premiered on 9 February 1893 at La Scala, Milan.

The Merry Wives of Windsor or Sir John Falstaff and the Merry Wives of Windsor is a comedy by William Shakespeare first published in 1602, though believed to have been written in or before 1597. The Windsor of the play's title is a reference to the town of Windsor, also the location of Windsor Castle in Berkshire, England. Though nominally set in the reign of Henry IV or early in the reign of Henry V, the play makes no pretence to exist outside contemporary Elizabethan-era English middle-class life. It features the character Sir John Falstaff, the fat knight who had previously been featured in Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2. It has been adapted for the opera at least ten times. The play is one of Shakespeare's lesser-regarded works among literary critics. Tradition has it that The Merry Wives of Windsor was written at the request of Queen Elizabeth I. After watching Henry IV, Part 1, she asked Shakespeare to write a play depicting Falstaff in love.

Henry IV, Part 1 is a history play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written not later than 1597. The play dramatises part of the reign of King Henry IV of England, beginning with the battle at Homildon Hill late in 1402, and ending with King Henry's victory in the Battle of Shrewsbury in mid-1403. In parallel to the political conflict between King Henry and a rebellious faction of nobles, the play depicts the escapades of King Henry's son, Prince Hal, and his eventual return to court and favour.

John Shakespeare was an English businessman and politician who was the father of William Shakespeare. Active in Stratford-upon-Avon, he was a glover and whittawer by trade. Shakespeare was elected to several municipal offices, serving as an alderman and culminating in a term as bailiff, the chief magistrate of the town council, and mayor of Stratford in 1568, before he fell on hard times for reasons unknown. His fortunes later revived and he was granted a coat of arms five years before his death, probably at the instigation and expense of his son, the actor and playwright.

Henry IV, Part 2 is a history play by William Shakespeare believed to have been written between 1596 and 1599. It is the third part of a tetralogy, preceded by Richard II and Henry IV, Part 1 and succeeded by Henry V.

Sir Thomas Lucy was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons in 1571 and 1585. He was a magistrate in Warwickshire, but is best known for his links to William Shakespeare. As a Protestant activist, he came into conflict with Shakespeare's Catholic relatives, and there are stories that the young Shakespeare himself had clashes with him.

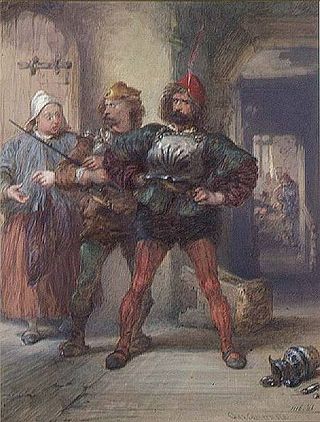

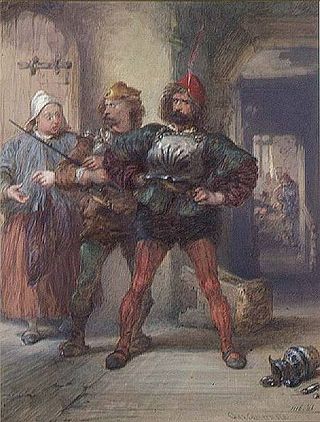

Ancient Pistol is a swaggering soldier who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare. Although full of grandiose boasts about his prowess, he is essentially a coward. The character is introduced in Henry IV, Part 2, and reappears in The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry V.

John Woodvine is an English actor who has appeared in more than 70 theatre productions, as well as a similar number of television and film roles.

Chimes at Midnight is a 1966 period comedy-drama film written, directed by, and starring Orson Welles. Its plot centers on William Shakespeare's recurring character Sir John Falstaff and his fatherly relationship with Prince Hal, who must choose loyalty to Falstaff or to his father, King Henry IV. The English-language film was an international co-production of Spain, France, and Switzerland.

Mistress Nell Quickly is a fictional character who appears in several plays by William Shakespeare. She is an inn-keeper, who runs the Boar's Head Tavern, at which Sir John Falstaff and his disreputable cronies congregate.

Dorothy "Doll" Tearsheet is a fictional character who appears in Shakespeare's play Henry IV, Part 2. She is a prostitute who frequents the Boar's Head Inn in Eastcheap. Doll is close friends with Mistress Quickly, the proprietress of the tavern, who procures her services for Falstaff.

Sir John in Love is an opera in four acts by the English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. The libretto, by the composer himself, is based on Shakespeare's The Merry Wives of Windsor and supplemented with texts by Philip Sidney, Thomas Middleton, Ben Jonson, and Beaumont and Fletcher. The music deploys English folk tunes, including "Greensleeves". Originally titled The Fat Knight, the opera premiered at the Parry Opera Theatre, Royal College of Music, London, on 21 March 1929. Its first professional performance was on 9 April 1946 at Sadler's Wells Theatre.

James Durno (c.1745–1795) was a British historical painter who spent most of his career in Rome.

Bardolph is a fictional character who appears in four plays by William Shakespeare. He is a thief who forms part of the entourage of Sir John Falstaff. His grossly inflamed nose and constantly flushed, carbuncle-covered face is a repeated subject for Falstaff's and Prince Hal's comic insults and word-play. Though his role in each play is minor, he often adds comic relief, and helps illustrate the personality change in Henry from Prince to King.

Falstaff's Wedding is a play by William Kenrick. It is a sequel to Shakespeare's plays Henry IV, Part 2 and The Merry Wives of Windsor. Most of the characters are carried over from the two Shakespeare plays. The play was first staged in 1766, but was not a success. It was infrequently revived thereafter.

Corporal Nym is a fictional character who appears in two Shakespeare plays, The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry V. He later appears in spin-off works by other writers. Nym is a soldier and criminal follower of Sir John Falstaff and a friend and rival of Ancient Pistol.

Edward "Ned" Poins, generally referred to as "Poins", is a fictional character who appears in two plays by William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part 1 and Henry IV, Part 2. He is also mentioned in The Merry Wives of Windsor. Poins is Prince Hal's closest friend during his wild youth. He devises various schemes to ridicule Falstaff, his rival for Hal's affections.