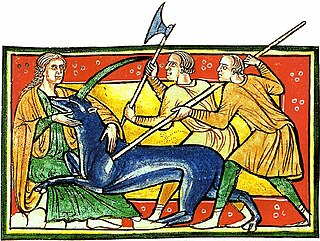

The Aberdeen Bestiary is a 12th-century English illuminated manuscript bestiary that was first listed in 1542 in the inventory of the Old Royal Library at the Palace of Westminster. Due to similarities, it is often considered to be the "sister" manuscript of the Ashmole Bestiary. The connection between the ancient Greek didactic text Physiologus and similar bestiary manuscripts is also often noted. Information about the manuscript's origins and patrons are circumstantial, although the manuscript most likely originated from the 13th century and was owned by a wealthy ecclesiastical patron from north or south England. Currently, the Aberdeen Bestiary resides in the Aberdeen University Library in Scotland.

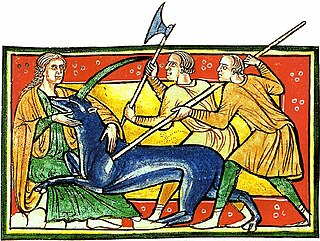

A bestiary is a compendium of beasts. Originating in the ancient world, bestiaries were made popular in the Middle Ages in illustrated volumes that described various animals and even rocks. The natural history and illustration of each beast was usually accompanied by a moral lesson. This reflected the belief that the world itself was the Word of God and that every living thing had its own special meaning. For example, the pelican, which was believed to tear open its breast to bring its young to life with its own blood, was a living representation of Jesus. Thus the bestiary is also a reference to the symbolic language of animals in Western Christian art and literature.

The Physiologus is a didactic Christian text written or compiled in Greek by an unknown author in Alexandria. Its composition has been traditionally dated to the 2nd century AD by readers who saw parallels with writings of Clement of Alexandria, who is asserted to have known the text, though Alan Scott has made a case for a date at the end of the 3rd or in the 4th century. The Physiologus consists of descriptions of animals, birds, and fantastic creatures, sometimes stones and plants, provided with moral content. Each animal is described, and an anecdote follows, from which the moral and symbolic qualities of the animal are derived. Manuscripts are often, but not always, given illustrations, often lavish.

In Greek mythology, sirens are humanlike beings with alluring voices; they appear in a scene in the Odyssey in which Odysseus saves his crew's lives. Roman poets place them on some small islands called Sirenum scopuli. In some later, rationalized traditions, the literal geography of the "flowery" island of Anthemoessa, or Anthemusa, is fixed: sometimes on Cape Pelorum and at others in the islands known as the Sirenuse, near Paestum, or in Capreae. All such locations were surrounded by cliffs and rocks.

In folklore, a mermaid is an aquatic creature with the head and upper body of a female human and the tail of a fish. Mermaids appear in the folklore of many cultures worldwide, including Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The manticore or mantichore is a Persian legendary creature similar to the Egyptian sphinx that proliferated in Western European medieval art as well. It has the head of a human, the body of a lion, and the tail of a scorpion or a tail of venomous spines similar to porcupine quills. There are some accounts that the spines can be launched like arrows. It eats its victims whole, using its three rows of teeth, and leaves no bones behind.

British Library, Egerton MS 609 is a Breton Gospel Book from the late or third quarter of the ninth century. It was created in France, though the exact location is unknown. The large decorative letters which form the beginning of each Gospel are similar to the letters found in Carolingian manuscripts, but the decoration of these letters is closer to that found in insular manuscripts, such as the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels. However, the decoration in the Breton Gospel Book is simpler and more geometric in form than that found in the Insular manuscripts. The manuscript contains the Latin text of St Jerome's letter to Pope Damasus, St. Jerome's commentary on Matthew, and the four Gospels, along with prefatory material and canon tables. This manuscript is part of the Egerton Collection in the British Library.

The Ashmole Bestiary is a late 12th or early 13th century English illuminated manuscript Bestiary containing a creation story and detailed allegorical descriptions of over 100 animals. Rich colour miniatures of the animals are also included.

The idea that there are specific marine counterparts to land creatures, inherited from the writers on natural history in Antiquity, was firmly believed in Islam and in Medieval Europe. It is exemplified by the creatures represented in the medieval animal encyclopedias called bestiaries, and in the parallels drawn in the moralising attributes attached to each. "The creation was a mathematical diagram drawn in parallel lines," T. H. White said a propos the bestiary he translated. "Things did not only have a moral they often had physical counterparts in other strata. There was a horse in the land and a sea-horse in the sea. For that matter there was probably a Pegasus in heaven". The idea of perfect analogies in the fauna of land and sea was considered part of the perfect symmetry of the Creator's plan, offered as the "book of nature" to mankind, for which a text could be found in Job:

But ask the animals, and they will teach you, or the birds of the air, and they will tell you; or speak to the earth, and it will teach you, or let the fish of the sea inform you. Which of all these does not know that the hand of the Lord has done this? In his hand is the life of every creature and the breath of all mankind.

The Myrmecoleon or Ant-lion is a fantastical animal from classical times, possibly derived from an error in the Septuagint version of the book of Job, reappearing in the Greek Christian Physiologus of the 3rd or 4th century A.D.

The Queen Mary Psalter is a fourteenth-century English psalter named after Mary I of England, who gained possession of it in 1553. The psalter is noted for its beauty and the lavishness of its illustration, and has been called "one of the most extensively illustrated psalters ever produced in Western Europe" and "one of the choicest treasures of the magnificent collection of illuminated MSS. in the British Museum".

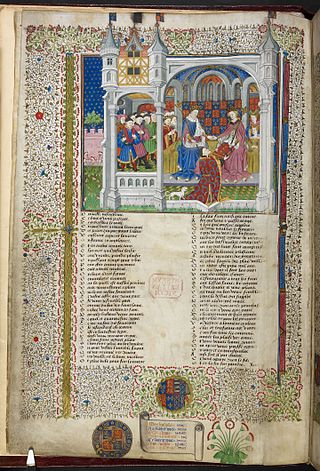

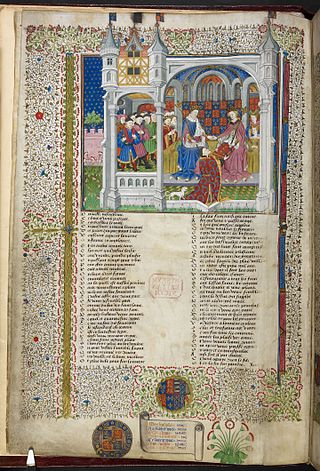

The Royal manuscripts are one of the "closed collections" of the British Library, consisting of some 2,000 manuscripts collected by the sovereigns of England in the "Old Royal Library" and given to the British Museum by George II in 1757. They are still catalogued with call numbers using the prefix "Royal" in the style "Royal MS 2. B. V". As a collection, the Royal manuscripts date back to Edward IV, though many earlier manuscripts were added to the collection before it was donated. Though the collection was therefore formed entirely after the invention of printing, luxury illuminated manuscripts continued to be commissioned by royalty in England as elsewhere until well into the 16th century. The collection was expanded under Henry VIII by confiscations in the Dissolution of the Monasteries and after the falls of Henry's ministers Cardinal Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell. Many older manuscripts were presented to monarchs as gifts; perhaps the most important manuscript in the collection, the Codex Alexandrinus, was presented to Charles I in recognition of the diplomatic efforts of his father James I to help the Eastern Orthodox churches under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. The date and means of entry into the collection can only be guessed at in many if not most cases. Now the collection is closed in the sense that no new items have been added to it since it was donated to the nation.

The Histoire ancienne jusqu'à César is the first medieval French prose compilation of stories of antiquity, mostly consisting of the so-called Matter of Troy and of Rome, besides text from the Bible and other histories. Composed in the early 13th century in northern France, it told the history of the world from the creation to the time of Julius Caesar. Often copied, it underwent an important redaction in Italy in the 14th century; its influence extended into the Renaissance. In manuscripts from the 14th and 15th centuries it was frequently found together with the Faits des Romains, which continued the history of the Roman Empire.

The Worksop Bestiary, also known as the Morgan Bestiary, most likely from Lincoln or York, England, is an illuminated manuscript created around 1185, containing a bestiary and other compiled medieval Latin texts on natural history. The manuscript has influenced many other bestiaries throughout the medieval world and is possibly part of the same group as the Aberdeen Bestiary, Alnwick Bestiary, St.Petersburg Bestiary, and other similar Bestiaries. Now residing in the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, the manuscript has had a long history of church, royal, government, and scholarly ownership.

The Icelandic Physiologus is a translation into Old Icelandic of a Latin translation of the 2nd-century Greek Physiologus. It survives in fragmentary form in two manuscripts, both dating from around 1200, making them the earliest illustrated manuscripts from Iceland and among the earliest Icelandic manuscripts generally. The fragments are significantly different from each other and either represent copies from two separate exemplars or different reworkings of the same text. Both texts also contain material that is not found in standard versions of the Physiologus.

Philip de Thaun was the first Anglo-Norman poet. He is the first known poet to write in the Anglo-Norman French vernacular language, rather than Latin. Two poems by him are signed with his name, making his authorship of both clear. A further poem is probably written by him as it bears many writing similarities to his other two poems.

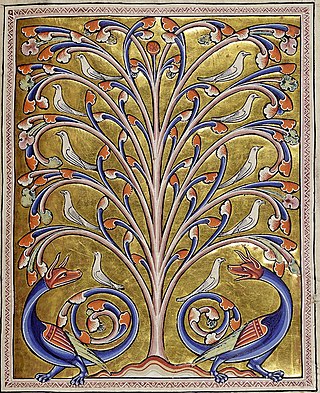

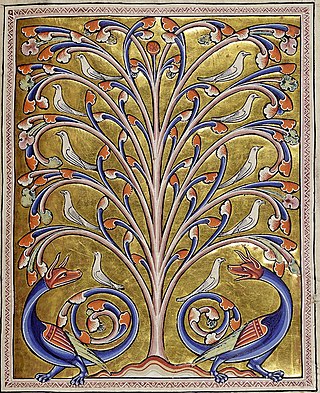

The peridexion tree or perindens is a mythological tree discussed in the Physiologus, an early Greek-language Christian didactic text and compendium, and popular in medieval bestiaries. It is described as growing in India, attracting doves and deterring serpents, making for a fable about Christian salvation.

The Zirc Bestiary is a 15th-century Hungarian illuminated manuscript copy of a medieval bestiary, a book describing the appearance and habits of a number of familiar and exotic animals, both real and legendary. The animals' characteristics are frequently allegorized, with the addition of a Christian moral. The Latin-language work was kept in the Cistercian Zirc Abbey, now it belongs to the property of the National Széchényi Library (OSZK).