Plot

A brief sketch of Irish history since the Easter Rising of 1916 is drawn, in which the hopes of the revolutionary founders of the Irish Free State for a republican society are dashed. In the film, the writer Seán Ó Faoláin argues that, after the Irish revolutionary period:

the kind of society that actually grew up was a society of what I call 'urbanised peasants'... which was without moral courage, constantly observing a self-interested silence,... in constant alliance with a completely obscurantist, repressive, regressive and uncultivated church...—a society utterly alien to the ideas of republicanism.

The film covers the continuing dominance of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy with scenes of hunting and equestrian events. The country's lack of independence from American foreign policy is touched on; Conor Cruise O'Brien is critical of Ireland's following of American policy in the United Nations General Assembly since 1957, and argues that Ireland should follow Sweden's more independent lead.

The editor of The Irish Times , Douglas Gageby, is in favour of open debate over the contraceptive pill in the correspondence columns of his newspaper, and reflects on the emerging difficulties of censorship. He points out the difficulties of the older generation adapting to change, while people under thirty are more positive. Students at Trinity College Dublin though, are critical of the Irish media, including The Irish Times.

A policy of the 500,000 strong Gaelic Athletic Association, finally dropped in 1971, is discussed. This was for the suspension of members found to have watched or participated in the foreign, or more precisely the 'English', sports of soccer, cricket, rugby, and hockey. The ban applied to clubs whose activities included these pastimes.

The emigration of Irish writers is viewed as the country's most "notorious" export because of state censorship. A roll call of native and international writers whose work had been banned is accompanied by church bells rung as at a funeral. A member of the censorship appeal board is interviewed. Professor Liam Ó Briain contrasts Ireland with Britain where he sees the complete loss of faith, moral values and the abolition of "sin". He recounts that a friend, Jimmy Montgomery, while film censor, had to make decisions "for a while" on sound films before the equipment to hear the soundtrack had arrived. Ó Briain though, does recognise the difficulties of sustaining faith in the context of scientific and philosophical developments.

The hold of the clergy on education in schools and colleges is pointed out. In a Christian Brothers school, a class of schoolboys, in Lennon's old classroom, [1] are shown regurgitating the catechism on the effects of original sin. Irish schools were single sex only. For this reason, contact between adolescents and young of both sexes for the middle classes is restricted to the tennis club dance halls where strict decorum is observed. Irish women are depicted as passive, always waiting for men to make contact with them. The old ways there are contrasted with a much more modern working class venue.

The "close involvement" of Irish politicians with the clergy is seen as "not so much a villainous conspiracy as a bad habit". Before the Second Vatican Council the role of the clergy was "not to disturb the simple faith of the people". Subsequently, the hierarchy "reluctantly" allowed some relaxation. Father Michael Cleary, posthumously the subject of a scandal, is shown singing a secular song "Chattanoogie Shoe Shine Boy" in a women's hospital ward. At a wedding reception he is an active participant. In an interview, he sees this show of camaraderie as a means of reaching the young, and showing himself to be "on their wavelength". He insists the clergy is not against sex, and that celibacy is a problem for the priest; "personally" he would wish to be married and have a family, but their absence is a sacrifice he makes as a priest.

The Catholic clergy's grip on family life is examined. An anonymous "young married woman" relates her history. After three children in as many years, the couple practice coitus interruptus in the safe period. At confession, the priest tells her to sleep separately from her husband rather than participate in his sin. They do however stop their method of contraception, and the woman miscarries. Though she remains a practising Catholic, priests and doctors are seen as solely being on the side of men.

The clerical and political orthodoxy outlined is viewed as being about to change. Though he is critical of "pop orchestras" and "jazz bands", the censor Ó Briain, wishes the emerging world well and hopes it will develop its own traditions. The film ends on a freeze frame of two boys in a boat; one of them is looking straight at the camera.

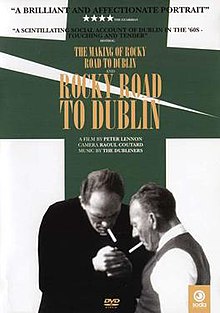

Production

Peter Lennon, then a junior feature writer for The Guardian in Paris, was told by friends in his week back in Dublin covering the theatre festival, that Ireland was changing: "'censorship was a thing of the past' they told me." [1] No one paid any attention to the clergy, it was claimed. Gaining permission from his newspaper to write a series of articles about the situation in Ireland, he found this was not so. The articles gained much notice lasting over a year, and he was able to make the film when his friend, Victor Herbert, who had made a fortune selling mutual funds, agreed to finance it.

Half of the film was shot in the gap before Raoul Coutard was committed to shooting Truffaut's The Bride Wore Black and the remainder before his commitment to Godard's Week End . [2] At the time, Lennon chose to use the cameraman because Coutard was the only person he was aware able to shoot in an informal way. [3]

Although shot in colour, it was printed in black-and-white, partly because of the experimental and unstable reversal film stock used, and partly because Lennon thought that monochrome was more in keeping with the tone of the film. [1]

Response in Ireland

The film could not be officially banned, since it contained no sex, but the Irish government did prevent it from being screened in cinemas or by state broadcaster RTÉ. After a single press screening in Dublin in 1967 – which provoked a hostile reaction from newspapers and RTÉ – Lennon entered it for that year's Cork Film Festival, but it was rejected on the grounds that it had already been shown in the capital. It was only when the film was chosen to represent Ireland at the 1968 Cannes Film Festival that the Cork organisers were embarrassed into changing their decision at the next festival – held in September 1968. However, the organisers gave it a lunchtime screening on the day that all the media covering the Festival were invited "to a free oyster-and-Guinness lunch in Kenmore, 70 miles away." [4] Lennon organised his own screening in Cork the following day, the resulting furore leading to a single Dublin cinema – the International Film Theatre – giving it a seven-week run to packed audiences.

At Cannes, it was chosen as one of eight films to be shown during critics' week at the 1968 Festival, but immediately after the screening Coutard's sometime collaborators François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard declared the Festival suspended in sympathy with the Paris students' strike, leading to a furious debate with Lennon and other filmmakers present. Despite this, screenings were organised for the same students, as well as striking workers besieged in the Renault plant.

The de facto ban in Ireland remained in place for more than thirty years – barring sporadic private screenings in the 1990s – until the film was restored in 2004 by the Irish Film Board and Loopline Films. At the same time, a new documentary, The Making of Rocky Road, was made by Paul Duane, examining the history of Rocky Road, and including BBC footage of Coutard and Lennon shooting Rocky Road in 1967, [5] and previously unseen film of the events in Cannes in 1968. Both films were released on DVD (Region 0 PAL) in 2005.