The Middle Ages in Romania began with the withdrawal of the Mongols, the last of the migrating populations to invade the territory of modern Romania, after their attack of 1241–1242. It came to an end with the reign of Michael the Brave (1593–1601) who managed, for a short time in 1600, to rule Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania, the three principalities whose territories were to be united some three centuries later to form Romania.

Bihar was an administrative county (comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary and a county of the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom and Principality of Transylvania. Most of its territory is now part of Romania, while a smaller western part belongs to Hungary. The capital of the county was Nagyvárad. Albrecht Dürer's father was from this county.

Litovoi, also Litvoy, was a Vlach/Romanian voivode in the 13th century whose territory comprised northern Oltenia in today's Romania.

The Karaš or Caraș is a 110-kilometre (68 mi) long river in the Banat region of Vojvodina, Serbia and Romania and a left tributary of the Danube. The Karaš drains an area of 1,400 square kilometres (540 sq mi) and although it has been channeled it is not navigable.

Dragoș, also known as Dragoș Vodă, or Dragoș the Founder was the first Voivode of Moldavia, who reigned in the middle of the 14th century, according to the earliest Moldavian chronicles. The same sources say that Dragoș came from Maramureş while chasing an aurochs or zimbru across the Carpathian Mountains. His descălecat, or "dismounting", on the banks of the Moldova River has traditionally been regarded as the symbol of the foundation of the Principality of Moldavia in Romanian historiography. Most details of his life are uncertain. Historians have identified him either with Dragoș of Bedeu or with Dragoș of Giulești, who were Vlach, or Romanian, landowners in the Kingdom of Hungary.

Bogdan I, or Bogdan the Founder, was the first independent ruler, or voivode, of Moldavia in the 1360s. He had initially been the voivode, or head, of the Vlachs in the Voivodeship of Maramureș in the Kingdom of Hungary. However, when the first certain record was made of him in 1343, he was mentioned as a former voivode who had become disloyal to Louis I of Hungary. He invaded the domains of a Vlach landowner who remained loyal to the king in 1349. Four years later, he was again mentioned as voivode in a charter, which was the last record of his presence in Maramureș.

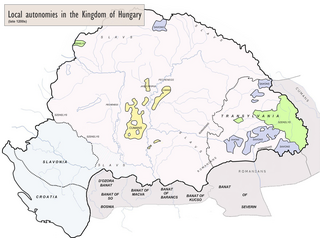

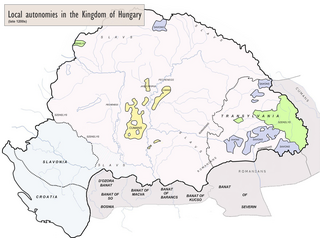

Universitas Valachorum is the Latin denomination for an Estate, an institution of self-government of the Romanians in medieval Transylvania, which then belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary.

The Decree of Turda was a 14th century decree by Louis I Anjou of Hungary that granted special privileges to the Transylvanian noblemen.

The Vlach law refers to the traditional Romanian common law as well as to various special laws and privileges enjoyed or enforced upon particularly pastoralist communities of Romanian stock or origin in European states of the Late Middle Ages and Early modern period, including in the two Romanian polities of Moldavia and Wallachia, as well as in the Kingdom of Hungary, the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Serbia, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, etc.

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Cumania was a Latin-rite bishopric west of the Siret River from 1228 to 1241. The lands incorporated into the diocese had been dominated by the nomadic Cumans since about 1100. Catholic missions began after Andrew II of Hungary granted Burzenland to the Teutonic Knights in 1211. After Andrew expelled the Knights from the territory in 1225, Dominican friars continued the Cuman mission. Robert, Archbishop of Esztergom baptized Boricius, an influential Cuman chieftain, two years later.

The founding of Wallachia, that is the establishment of the first independent Romanian principality, was achieved at the beginning of the 14th century, through the unification of smaller political units that had existed between the Carpathian Mountains, and the Rivers Danube, Siret and Milcov.

The Hunyadi family was one of the most powerful noble families in the Kingdom of Hungary during the 15th century. A member of the family, Matthias Corvinus, was King of Hungary from 1458 until 1490, King of Bohemia from 1469 until 1490, and Duke of Austria from 1487 until 1490. His illegitimate son, John Corvinus, ruled the Duchy of Troppau from 1485 until 1501, and five further Silesian duchies, including Bytom, Głubczyce, Loslau, Racibórz, and Tost, from 1485 until 1490. The Hunyadi coat-of-arms depicted a raven with a golden ring in its beak.

The Voivode of Transylvania was the highest-ranking official in Transylvania within the Kingdom of Hungary from the 12th century to the 16th century. Appointed by the monarchs, the voivodes – themselves also the heads or ispáns of Fehér County – were the superiors of the ispáns of all the other counties in the province.

The Transylvanian Diet was an important legislative, administrative and judicial body of the Principality of Transylvania between 1570 and 1867. The general assemblies of the Transylvanian noblemen and the joint assemblies of the representatives of the "Three Nations of Transylvania"—the noblemen, Székelys and Saxons—gave rise to its development. After the disintegration of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary in 1541, delegates from the counties of the eastern and northeastern territories of Hungary proper also attained the Transylvanian Diet, transforming it into a legal successor of the medieval Diets of Hungary.

The Middle Ages in the Banat started around 900. Around that time, Duke Glad ruled Banat, according to the Gesta Hungarorum. Archaeological finds and 10th-century sources evidence that Magyars settled in the lowlands in the early 10th century, but the survival of Avar, Slav and Bulgar communities can also be documented. A local chieftain, Ajtony, converted to Eastern Orthodoxy around 1000, but his attempts to control the delivery of salt on the Mureș River brought him into conflict with Stephen I of Hungary. Ajtony died fighting against the royal army in the first decades of the 11th century. His realm was transformed into a county of the Kingdom of Hungary. Counties were the most prominent units of royal administration.

The Banate of Severin or Banate of Szörény was a Hungarian political, military and administrative unit with a special role in the initially anti-Bulgarian, latterly anti-Ottoman defensive system of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. It was founded by Prince Béla in 1228.

The Count of the Székelys was the leader of the Hungarian-speaking Székelys in Transylvania, in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. First mentioned in royal charters of the 13th century, the counts were the highest-ranking royal officials in Székely Land. From around 1320 to the second half of the 15th century, the counts' jurisdiction included four Transylvanian Saxon districts, in addition to the seven Székely seats.

A conditional noble or predialist was a landowner in the Kingdom of Hungary who was obliged to render specific services to his lord in return for his landholding, in contrast with a "true nobleman of the realm" who held his estates free of such services. Most conditional nobles lived in the border territories of the kingdom, including Slavonia and Transylvania, but some of their groups possessed lands in estates of Roman Catholic prelates. Certain groups of conditional nobility, including the "ecclesiastic nobles" and the "nobles of Turopolje" preserved their specific status until the 19th century.

A knez or kenez was the hereditary leader of the Vlach (Romanian) communities, primarily in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary.

The boyars of Fogaras were a group of Vlach conditional nobles in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary and the Principality of Transylvania.