Samba is a name or prefix used for several rhythmic variants, such as samba urbano carioca, samba de roda, amongst many other forms of samba, mostly originated in the Rio de Janeiro and Bahia states.

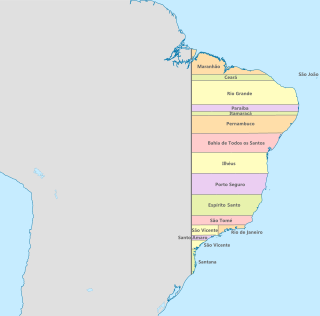

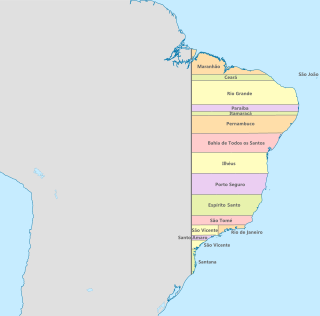

Colonial Brazil comprises the period from 1500, with the arrival of the Portuguese, until 1815, when Brazil was elevated to a kingdom in union with Portugal. During the 300 years of Brazilian colonial history, the main economic activities of the territory were based first on brazilwood extraction, which gave the territory its name; sugar production ; and finally on gold and diamond mining. Slaves, especially those brought from Africa, provided most of the workforce of the Brazilian export economy after a brief initial period of Indigenous slavery to cut brazilwood.

Luiz Roberto de Barros Mott or Luiz Mott in São Paulo, is an anthropologist and a gay rights activist in Brazil.

Afro-Brazilians are an ethno-racial group consisting of Brazilians with predominantly or total Sub-Saharan African ancestry, these stand out for having dark skin. Most multiracial Brazilians also have a range of degree of African ancestry. Brazilians whose African features are more evident are generally seen by others as Blacks and may identify themselves as such, while the ones with less noticeable African features may not be seen as such. However, Brazilians rarely use the term "Afro-Brazilian" as a term of ethnic identity and never in informal discourse.

The Candelária Church is an important historical Roman Catholic church in the city of Rio de Janeiro, in southeastern Brazil. It was built and decorated during a long period, from 1775 to the late 19th century. The church combines a Portuguese colonial Baroque façade with later Neoclassical and Neo-Renaissance interior elements.

Slavery in Brazil began long before the first Portuguese settlement. Later, colonists were heavily dependent on indigenous labor during the initial phases of settlement to maintain the subsistence economy, and natives were often captured by expeditions of bandeirantes. The importation of African slaves began midway through the 16th century, but the enslavement of indigenous peoples continued well into the 17th and 18th centuries. Europeans and Chinese were also enslaved.

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mariana is an archdiocese based in the city of Mariana in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais.

Afro-Brazilian literature has existed in Brazil since the mid-19th century with the publication of Maria Firmina dos Reis's novel Ursula in 1859. Other writers from the late 19th century and early 20th century include Machado de Assis, Cruz e Sousa and Lima Barreto. Yet, Afro-Brazilian literature as a genre that recognized the ethnic and cultural origins of the writer did not gain national prominence in Brazil until the 1970s with the revival of Black Consciousness politics known as the Movimento Negro.

Yeda Pessoa de Castro is a Brazilian ethnolinguist. With a PhD in African Languages at the National University of Zaire, she is a Technical Consultant in African Languages for the Museu da Língua Portuguesa at the Estação da Luz in São Paulo, a Member of the Academia de Letras da Bahia and of the ANPOLL's GT de Literatura Oral e Popular. Also is a Permanent Member of the Brazilian Scientific Committee of the Project "Slave Route" by UNESCO.

Maria José Motta de Oliveira, known as Zezé Motta, is a Brazilian actress and singer. She is considered one of the most important actresses in Brazil.

Maria Firmina dos Reis was a Brazilian author. She is considered Brazil's first black female novelist. In 1859, she published her first book Úrsula, which is considered the first Brazilian abolitionist novel. The book tells the story of a love triangle, in which the system of slavery is put into question.

Events from the year 2002 in Brazil

Lélia Gonzalez was a Brazilian intellectual, politician, professor, anthropologist and woman human rights defender.

Events in the year 1910 in Brazil.

Events in the year 1949 in Brazil.

Miss Brazil 2018, officially Miss Brazil Be Emotion 2018 was the 64th edition of the Miss Brazil pageant, held the at Riocentro in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on 26 May 2018.

Marie Rennotte was a Belgian-born Brazilian physician, teacher, and women's rights activist. She was active in the fight for women's rights. After earning her teaching credentials in Belgium and France, Rennotte taught for three years in Germany before moving to Brazil as a governess. Giving private lessons and teaching at a girls' school, she lived in Rio de Janeiro from 1878 to 1882. Hired to teach in the State of São Paulo, she moved to Piracicaba where from 1882 to 1889 she taught science, developed the curriculum, and enhanced the reputation of the Colégio Piracicabano. The co-educational school was an innovative institution offering equal education to girls and boys.

The General Company of Grão-Pará and Maranhão was a Portuguese chartered company founded in 1755 by the Marquis of Pombal to develop and oversee commercial activity in the state of Grão-Pará and Maranhão, an administrative division of the colony of Brazil. Employees of the company were officially considered to be in the service of the Portuguese Crown and were responsible directly to Lisbon. The company greatly increased the volume of trade in Grão-Pará and Maranhão, though after the Marquis of Pombal fell from power Queen Maria I ordered it to be shut down in 1778.

Heloísa dos Reis Maranhão was a Brazilian novelist, playwright and short-story writer.

Esperança Garcia was an enslaved Afro-Brazilian and likely Creole woman in Brazil who is who is considered to have written the first earliest known slave petition in Brazil. On 6 September 1770, she sent a petition to free herself from slavery to the then-president of the province of São José do Piauí, Captaincy of Maranhão, Gonçalo Pereira Botelho de Castro. In the petition, she denounced the abuse and maltreatment of her and her son by the overseer of Fazenda Algodões.