Hezekiah, or Ezekias, was the son of Ahaz and the thirteenth king of Judah according to the Hebrew Bible.

Shebna was the royal steward in the reign of king Hezekiah of Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible.

The term Pool of Siloam refers to several rock-cut pools located southeast of the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. The pools were fed by the waters of the Gihon Spring, carried there by the Siloam tunnel.

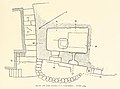

The City of David, known locally mostly as Wadi Hilweh, is the name given to an archaeological site considered by most scholars to be the original settlement core of Jerusalem during the Bronze and Iron Ages. It is situated on southern part of the eastern ridge of ancient Jerusalem, west of the Kidron Valley and east of the Tyropoeon Valley, to the immediate south of the Temple Mount.

Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau was a noted French Orientalist and archaeologist.

MMST is a word written in Paleo-Hebrew abjad script. It appears exclusively on LMLK seal inscriptions, seen in archaeological findings from the ancient Kingdom of Judah, whose meaning has been the subject of continual controversy.

Matthew 1:10 is the tenth verse of the first chapter in the Gospel of Matthew in the Bible. The verse is part of the section where the genealogy of Joseph, the father of Jesus, is listed.

Matthew 1:9 is the ninth verse of the first chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the Bible. The verse is part of the non-synoptic section where the genealogy of Joseph, the legal father of Jesus, is listed, or on non-Pauline interpretations the genealogy of Jesus. The purpose of the genealogy is to show descent from the line of kings, in particular David, as the Messiah was predicted to be the son of David, and descendant of Abraham.

The Siloam inscription, Silwan inscription or Shiloah inscription, known as KAI 189, is a Hebrew inscription found in the Siloam tunnel which brings water from the Gihon Spring to the Pool of Siloam, located in the City of David in East Jerusalem neighborhood of Silwan. The inscription records the construction of the tunnel, which has been dated to the 8th century BC on the basis of the writing style. It is the only known ancient inscription from ancient Israel and Judah which commemorates a public construction work, despite such inscriptions being commonplace in Egyptian and Mesopotamian archaeology.

The Paleo-Hebrew script, also Palaeo-Hebrew, Proto-Hebrew or Old Hebrew, is the writing system found in Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, including pre-Biblical and Biblical Hebrew, from southern Canaan, also known as the biblical kingdoms of Israel (Samaria) and Judah. It is considered to be the script used to record the original texts of the Bible due to its similarity to the Samaritan script; the Talmud states that the Samaritans still used this script. The Talmud described it as the "Livonaʾa script", translated by some as "Lebanon script". However, it has also been suggested that the name is a corrupted form of "Neapolitan", i.e. of Nablus. Use of the term "Paleo-Hebrew alphabet" is due to a 1954 suggestion by Solomon Birnbaum, who argued that "[t]o apply the term Phoenician [from Northern Canaan, today's Lebanon] to the script of the Hebrews [from Southern Canaan, today's Israel-Palestine] is hardly suitable". The Paleo-Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets are two slight regional variants of the same script.

David Ussishkin is an Israeli archaeologist and professor emeritus of archaeology.

The newer Siloam Tunnel, also known as Hezekiah's Tunnel, is a water tunnel that was carved within the City of David in ancient times, located in the modern-day Palestinian neighborhood of Silwan in East Jerusalem. The latter name is comes from its theorized origin under the reign of King Hezekiah of Judah in the late 8th and early 7th century BC, and corresponds to the "conduit" mentioned in 2 Kings 20 in the Tanakh. According to the Tanakh, King Hezekiah prepared Jerusalem for an impending siege by the Assyrians, by "blocking the source of the waters of the upper Gihon, and leading them straight down on the west to the City of David". By diverting the waters of the Gihon, he prevented the enemy forces under Sennacherib from gaining access to water. An older water system, sometimes called the Siloam Channel, partly fulfilled a similar purpose and dates back to the Canaanites.

Silwan or Siloam is a predominantly Palestinian district in East Jerusalem, on the southeastern outskirts of the current Old City of Jerusalem.

The Monolith of Silwan, also known as the Tomb of Pharaoh's Daughter, is a cuboid rock-cut tomb located in the Kidron Valley, in Silwan, Jerusalem dating from the period of the Kingdom of Judah. The Tomb of Pharaoh's Daughter refers to a 19th-century hypothesis that the tomb was built by Solomon for his wife, the Pharaoh's daughter. The structure, a typical Israelite rock-cut tomb, was previously capped by a pyramid structure like the Tomb of Zechariah. The upper edges of the monolith are fashioned in the shape of an Egyptian cornice. The pyramidal rock cap was cut into pieces and removed for quarry during the Roman era, leaving a flat roof. The tomb contains a single stone bench, indicating that it was designed for only one burial. Recent research indicates that the bench was the base of a sarcophagus hewn into the original building.

Azal (אצל), or Azel, is a location mentioned in the Book of Zechariah 14:5, in Bibles that use the Hebrew Masoretic Text as the source for this verse. In Bibles that follow the Greek Septuagint (LXX) rendering, depending upon the source manuscript used, Azal is transcribed Jasol, Jasod, or Asael (ασαηλ):

And ye shall flee to the valley of the mountains; for the valley of the mountains shall reach unto Azal: yea, ye shall flee, like as ye fled from before the earthquake in the days of Uzziah king of Judah.

The valley between the hills will be filled in, yes, it will be blocked as far as Jasol, it will be filled in as it was by the earthquake in the days of Uzziah king of Judah,

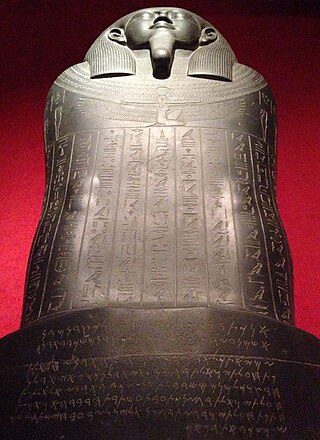

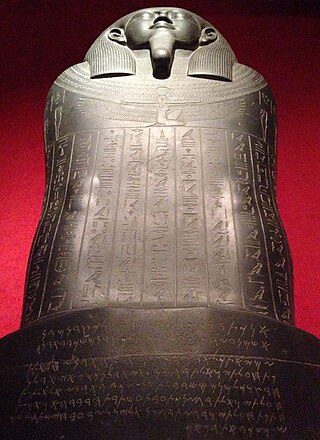

The Tabnit sarcophagus is the sarcophagus of the Phoenician King of Sidon Tabnit, the father of King Eshmunazar II. It is decorated with two separate and unrelated inscriptions – one in Egyptian hieroglyphs and one in the Phoenician alphabet. The latter contains a curse for those who open the tomb, promising impotency and loss of an afterlife.

The Silwan necropolis is the remains of a rock-cut cemetery assumed to have been used by the highest-ranking officials residing in Jerusalem. Its tombs were cut between the 9th and 7th centuries BC. It is situated on the rocky eastern slope of the Kidron Valley, facing the oldest part of Jerusalem. Part of the Palestinian district of Silwan was later built atop the necropolis.

2 Kings 18 is the eighteenth chapter of the second part of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the Second Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE. This chapter records the events during the reign of Hezekiah, the king of Judah, a part of the section comprising 2 Kings 18:1 to 20:21, with a parallel version in Isaiah 36–39.

2 Kings 19 is the nineteenth chapter of the second part of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the Second Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BC, with a supplement added in the sixth century BC. This chapter records the invasion of Assyrian to Judah during the reign of Hezekiah, the king of Judah, a part of the section comprising 2 Kings 18:1 to 20:21, with a parallel version in Isaiah 36–39.

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions, are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the societies and histories of the ancient Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic inscriptions may occur on stone slabs, pottery ostraca, ornaments, and range from simple names to full texts. The older inscriptions form a Canaanite–Aramaic dialect continuum, exemplified by writings which scholars have struggled to fit into either category, such as the Stele of Zakkur and the Deir Alla Inscription.