Sarnath is a place located 10 kilometres northeast of Varanasi, near the confluence of the Ganges and the Varuna rivers in Uttar Pradesh, India.

Saraca asoca, commonly known as the ashoka tree, is a plant belonging to the Detarioideae subfamily of the legume family. It is an important tree in the cultural traditions of the Indian subcontinent and adjacent areas. It is sometimes incorrectly known as Saraca indica. The flower of Ashoka tree is the state flower of Indian state of Odisha.

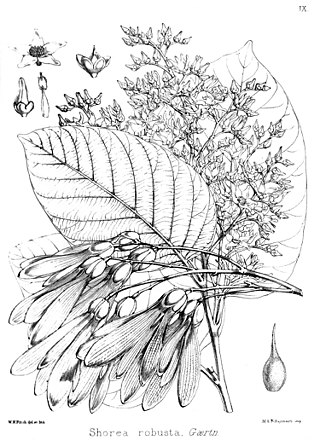

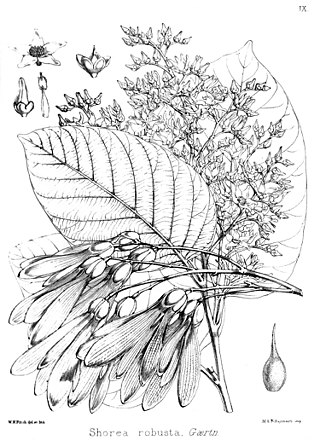

Shorea robusta, the sal tree, sāla, shala, sakhua, or sarai, is a species of tree in the family Dipterocarpaceae. The tree is native to India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Tibet and across the Himalayan regions.

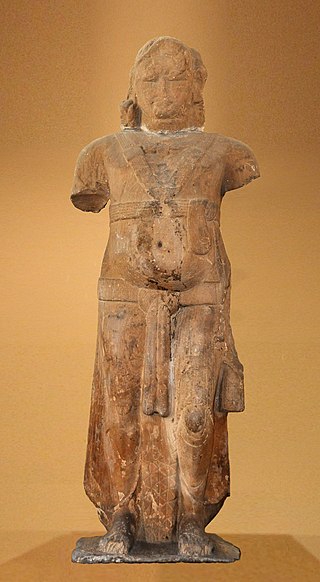

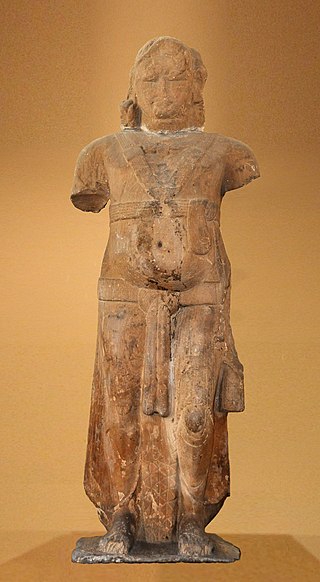

The Yakshas are a broad class of nature spirits, usually benevolent, but sometimes mischievous or capricious, connected with water, fertility, trees, the forest, treasure and wilderness. They appear in Hindu, Jain and Buddhist texts, as well as ancient and medieval era temples of South Asia and Southeast Asia as guardian deities. The feminine form of the word is IAST: Yakṣī or Yakshini.

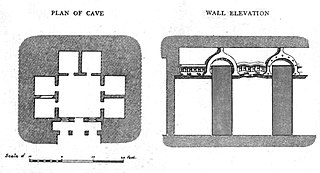

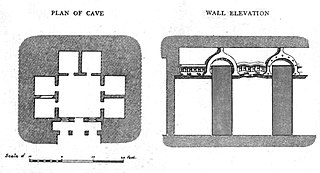

Vihāra generally refers to a Buddhist monastery for Buddhist renunciates, mostly in the Indian subcontinent. The concept is ancient and in early Sanskrit and Pali texts, it meant any arrangement of space or facilities for dwellings. The term evolved into an architectural concept wherein it refers to living quarters for monks with an open shared space or courtyard, particularly in Buddhism. The term is also found in Ajivika, Hindu and Jain monastic literature, usually referring to temporary refuge for wandering monks or nuns during the annual Indian monsoons. In modern Jainism, the monks continue to wander from town to town except during the rainy season (chaturmasya), and the term "vihara" refers to their wanderings.

A chaitya, chaitya hall, chaitya-griha, refers to a shrine, sanctuary, temple or prayer hall in Indian religions. The term is most common in Buddhism, where it refers to a space with a stupa and a rounded apse at the end opposite the entrance, and a high roof with a rounded profile. Strictly speaking, the chaitya is the stupa itself, and the Indian buildings are chaitya halls, but this distinction is often not observed. Outside India, the term is used by Buddhists for local styles of small stupa-like monuments in Nepal, Cambodia, Indonesia and elsewhere. In Thailand a stupa, not a stupa hall, is called a chedi. In the historical texts of Jainism and Hinduism, including those relating to architecture, chaitya refers to a temple, sanctuary or any sacred monument.

Shravasti ; Pali: 𑀲𑀸𑀯𑀢𑁆𑀣𑀻, romanized: Sāvatthī) is a town in Shravasti district in Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It was the capital of the ancient Indian kingdom of Kosala and the place where the Buddha lived most after his enlightenment. It is near the Rapti river in the northeastern part of Uttar Pradesh India, close to the Nepalese border.

Tribhaṅga or Tribunga is a standing body position or stance used in traditional Indian art and Indian classical dance forms like the Odissi, where the body bends in one direction at the knees, the other direction at the hips and then the other again at the shoulders and neck.

The dharmachakra or wheel of dharma is a widespread symbol used in Buddhism. The symbol also finds usage in Hinduism, particularly in places that underwent religious transformation, and in Jainism and in modern India.

Sculpture in the Indian subcontinent, partly because of the climate of the Indian subcontinent makes the long-term survival of organic materials difficult, essentially consists of sculpture of stone, metal or terracotta. It is clear there was a great deal of painting, and sculpture in wood and ivory, during these periods, but there are only a few survivals. The main Indian religions had all, after hesitant starts, developed the use of religious sculpture by around the start of the Common Era, and the use of stone was becoming increasingly widespread.

Nagarjunakonda: Nāgārjunikoṇḍa, meaning Nagarjuna Hill) is a historical town, now an island located near Nagarjuna Sagar in Palnadu district of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. It is one of India's richest Buddhist sites, and now lies almost entirely under the lake created by the Nagarjuna Sagar Dam. With the construction of the dam, the archaeological relics at Nagarjunakonda were submerged, and had to be excavated and transferred to higher land, which has become an island.

VicitracittaCalambur Sivaramamurti FRAS (1909–1983) was an Indian museologist, art historian and epigraphist who is primarily known for his work as curator in the Government Museum, Chennai. and Sanskrit scholar. His entire life has been devoted to the study and exposition of various aspects of Indian art. Apart from authoring several monographs, guide books on Indian art, he also wrote a seminal work on South Indian epigraphy.

Hindu architecture is the traditional system of Indian architecture for structures such as temples, monasteries, statues, homes, market places, gardens and town planning as described in Hindu texts. The architectural guidelines survive in Sanskrit manuscripts and in some cases also in other regional languages. These texts include the Vastu shastras, Shilpa Shastras, the Brihat Samhita, architectural portions of the Puranas and the Agamas, and regional texts such as the Manasara among others.

Kushinagar is a town in the Kushinagar district in Uttar Pradesh, India. Located 53 kilometres east of Gorakhpur on National Highway 27, Kushinagar is an important and popular Buddhist pilgrimage site, where Buddhists believe Gautama Buddha attained parinirvana.

Jain art refers to religious works of art associated with Jainism. Even though Jainism has spread only in some parts of India, it has made a significant contribution to Indian art and architecture.

The Buddhapad Hoard or Buddam Hoard is a large cache of Buddhist and Jain sculptures found near the town of Buddam in Andhra Pradesh, southern India. Since 1905, it has formed an important part of the British Museum's South Asian collection. Dating from 6th-8th centuries AD, the style of craftsmanship fuses the northern influences of the Gupta period with the southern traditions of the Deccan, which in turn greatly influenced Buddhist art in South East Asia in subsequent centuries.

The Art of Mathura refers to a particular school of Indian art, almost entirely surviving in the form of sculpture, starting in the 2nd century BCE, which centered on the city of Mathura, in central northern India, during a period in which Buddhism, Jainism together with Hinduism flourished in India. Mathura "was the first artistic center to produce devotional icons for all the three faiths", and the pre-eminent center of religious artistic expression in India at least until the Gupta period, and was influential throughout the sub-continent.

Jain hoysala complex in Halebidu, Hassan district consists of three Jain Basadis dedicated to the Jain Tirthankars Parshvanatha, Shantinatha and Adinatha. The complex is situated near Kedareshwara temple and Dwarasamudra lake. The temple complex also includes a step well called Hulikere Kalyani.

A śālā (Shala) is a Sanskrit term that means any "house, space, covered pavilion or enclosure" in Indian architecture. In other contexts śālā – also spelled calai or salai in South India – means a feeding house or a college of higher studies linked to a Hindu or Jain temple and supported by local population and wealthy patrons. In the early Buddhist literature of India, śālā means a "hut, cell, hall, pavilion or shed" as in Vedic śālā, Aggiśālā, Paniyaśālā.

Chitra or citra is an Indian genre of art that includes painting, sketch and any art form of delineation. The earliest mention of the term Chitra in the context of painting or picture is found in some of the ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism and Pali texts of Buddhism.