Assyria was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC, which eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC to the 7th century BC.

The Kingdom of Israel, also called the Northern Kingdom or the Kingdom of Samaria, was an Israelite kingdom that existed in the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Its beginnings date back to the first half of the 10th century BCE. It controlled the areas of Samaria, Galilee and parts of Transjordan; the former two regions underwent a period in which a large number of new settlements were established shortly after the kingdom came into existence. It had four capital cities in succession: Shiloh, Shechem, Tirzah, and the city of Samaria. In the 9th century BCE, it was ruled by the Omride dynasty, whose political centre was the city of Samaria.

Samaria, the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron, is used as a historical and biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is known to the Palestinians in Arabic under two names, Samirah, and Mount Nablus.

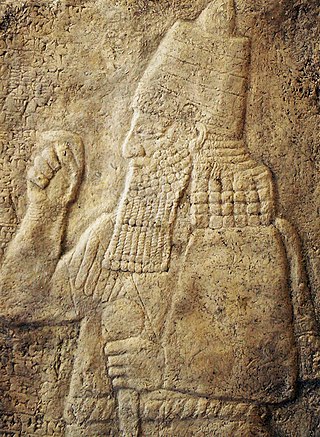

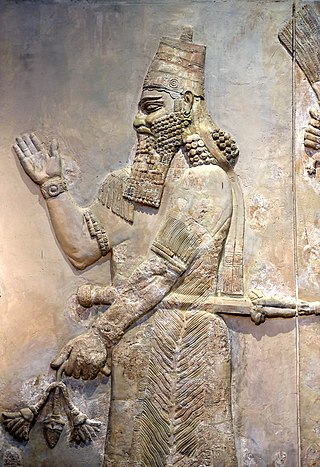

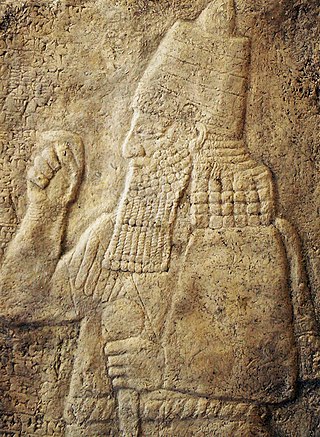

Sennacherib was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705 BC to his own death in 681 BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous Assyrian kings for the role he plays in the Hebrew Bible, which describes his campaign in the Levant. Other events of his reign include his destruction of the city of Babylon in 689 BC and his renovation and expansion of the last great Assyrian capital, Nineveh.

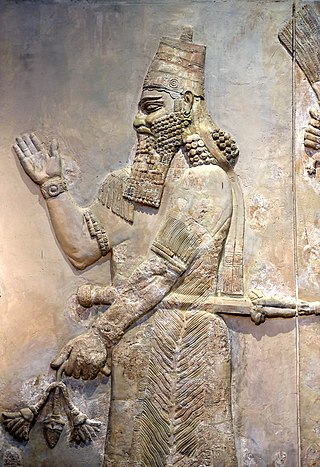

Tiglath-Pileser III was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 745 BC to his death in 727. One of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings, Tiglath-Pileser ended a period of Assyrian stagnation, introduced numerous political and military reforms and more than doubled the lands under Assyrian control. Because of the massive expansion and centralization of Assyrian territory and establishment of a standing army, some researchers consider Tiglath-Pileser's reign to mark the true transition of Assyria into an empire. The reforms and methods of control introduced under Tiglath-Pileser laid the groundwork for policies enacted not only by later Assyrian kings but also by later empires for millennia after his death.

Sargon II was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III, Sargon is generally believed to have become king after overthrowing Shalmaneser V, probably his brother. He is typically considered the founder of a new dynastic line, the Sargonid dynasty.

Shalmaneser V was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Tiglath-Pileser III in 727 BC to his deposition and death in 722 BC. Though Shalmaneser V's brief reign is poorly known from contemporary sources, he remains known for the conquest of Samaria and the fall of the Kingdom of Israel, though the conclusion of that campaign is sometimes attributed to his successor, Sargon II, instead.

The history of the Assyrians encompasses nearly five millennia, covering the history of the ancient Mesopotamian civilization of Assyria, including its territory, culture and people, as well as the later history of the Assyrian people after the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 609 BC. For purposes of historiography, ancient Assyrian history is often divided by modern researchers, based on political events and gradual changes in language, into the Early Assyrian, Old Assyrian, Middle Assyrian, Neo-Assyrian and post-imperial periods., Sassanid era Asoristan from 240 AD until 637 AD and the post Islamic Conquest period until the present day.

During the Middle Assyrian Empire and the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Phoenicia, what is today known as Lebanon and coastal Syria, came under Assyrian rule on several occasions.

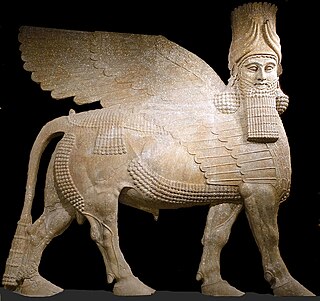

The Neo-Assyrian Empire arose in the 10th century BC. Ashurnasirpal II is credited for utilizing sound strategy in his wars of conquest. While aiming to secure defensible frontiers, he would launch raids further inland against his opponents as a means of securing economic benefit, as he did when campaigning in the Levant. The result meant that the economic prosperity of the region would fuel the Assyrian war machine.

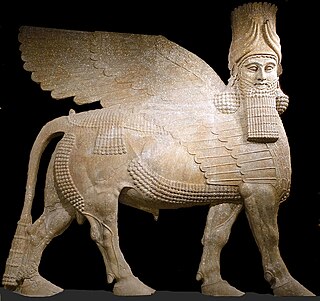

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, North Africa and East Mediterranean throughout much of the 9th to 7th centuries BC, becoming the largest empire in history up to that point. Because of its geopolitical dominance and ideology based in world domination, the Neo-Assyrian Empire is by many researchers regarded to have been the first world empire in history. It influenced other empires of the ancient world culturally, administratively, and militarily, including the Neo-Babylonians, the Achaemenids, and the Seleucids. At its height, the empire was the strongest military power in the world and ruled over all of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Egypt, as well as parts of Anatolia, Arabia and modern-day Iran and Armenia.

The Middle Assyrian Empire was the third stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of Assyria from the accession of Ashur-uballit I c. 1363 BC and the rise of Assyria as a territorial kingdom to the death of Ashur-dan II in 912 BC. The Middle Assyrian Empire was Assyria's first period of ascendancy as an empire. Though the empire experienced successive periods of expansion and decline, it remained the dominant power of northern Mesopotamia throughout the period. In terms of Assyrian history, the Middle Assyrian period was marked by important social, political and religious developments, including the rising prominence of both the Assyrian king and the Assyrian national deity Ashur.

The Assyrian captivity, also called the Assyrian exile, is the period in the history of ancient Israel and Judah during which several thousand Israelites from the Kingdom of Israel were dispossessed and forcibly relocated by the Neo-Assyrian Empire. One of many instances attesting Assyrian resettlement policy, this mass deportation of the Israelite nation began immediately after the Assyrian conquest of Israel, which was overseen by the Assyrian kings Tiglath-Pileser III and Shalmaneser V. The later Assyrian kings Sargon II and Sennacherib also managed to subjugate the Israelites in the neighbouring Kingdom of Judah following the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem in 701 BC, but were unable to annex their territory outright. The Assyrian captivity's victims are known as the Ten Lost Tribes, and Judah was left as the sole Israelite kingdom until the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in 587 BC, which resulted in the Babylonian captivity of the Jewish people. Not all of Israel's populace was deported by the Assyrians; those who were not expelled from the former kingdom's territory eventually became known as the Samaritan people.

Assyrian continuity is the study of continuity between the modern Assyrian people, a recognised Semitic indigenous ethnic, religious, and linguistic minority in Western Asia and the people of Ancient Mesopotamia in general and ancient Assyria in particular. Assyrian continuity and Mesopotamian heritage is a key part of the identity of the modern Assyrian people. No archaeological, genetic, linguistic, anthropological, or written historical evidence exists of the original Assyrian and Mesopotamian population being exterminated, removed, bred out, or replaced in the aftermath of the fall of the Assyrian Empire. Modern contemporary scholarship "almost unilaterally" supports Assyrian continuity, recognizing the modern Assyrians as the ethnic, linguistic, historical, and genetic descendants of the East Assyrian-speaking population of Bronze Age and Iron Age Assyria specifically, and Mesopotamia in general, which were composed of both the old native Assyrian population and of neighboring settlers in the Assyrian heartland.

The timeline of ancient Assyria can be broken down into three main eras: the Old Assyrian period, Middle Assyrian Empire, and Neo-Assyrian Empire. Modern scholars typically also recognize an Early period preceding the Old Assyrian period and a post-imperial period succeeding the Neo-Assyrian period.

The Sargonid dynasty was the final ruling dynasty of Assyria, ruling as kings of Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian Empire for just over a century from the ascent of Sargon II in 722 BC to the fall of Assyria in 609 BC. Although Assyria would ultimately fall during their rule, the Sargonid dynasty ruled the country during the apex of its power and Sargon II's three immediate successors Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal are generally regarded as three of the greatest Assyrian monarchs. Though the dynasty encompasses seven Assyrian kings, two vassal kings in Babylonia and numerous princes and princesses, the term Sargonids is sometimes used solely for Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.

In the three centuries starting with the reign of Ashur-dan II, the Neo-Assyrian Empire practiced a policy of resettlement of population groups in its territories. The majority of the resettlements were done with careful planning by the government in order to strengthen the empire. For example, a population might have been moved around to spread agricultural techniques or develop new lands. It could have also been done as punishment for political enemies, as an alternative to execution. In other cases, the selected elites of a conquered territory were moved to the Assyrian empire to enrich and increase the knowledge in the empire's centre.

The post-imperial period was the final stage of ancient Assyrian history, covering the history of the Assyrian heartland from the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 609 BC to the final sack and destruction of Assur, Assyria's ancient religious capital, by the Sasanian Empire c. AD 240. There was no independent Assyrian state during this time, with Assur and other Assyrian cities instead falling under the control of the successive Median, Neo-Babylonian, Achaemenid, Seleucid and Parthian empires. The period was marked by the continuance of ancient Assyrian culture, traditions and religion, despite the lack of an Assyrian kingdom. The ancient Assyrian dialect of the Akkadian language went extinct however, completely replaced by Aramaic by the 5th century BC.

Sargon II ruled the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 to 705 BC as one of its most successful kings. In his final military campaign, Sargon was killed in battle in the south-eastern Anatolian region Tabal and the Assyrian army was unable to retrieve his body, which meant that he could not undergo the traditional royal Assyrian burial. In ancient Mesopotamia, not being buried was believed to condemn the dead to becoming a hungry and restless ghost for eternity. As a result, the Assyrians believed that Sargon must have committed some grave sin in order to suffer this fate. His son and successor Sennacherib, convinced of Sargon's sin, consequently spent much effort to distance himself from his father and to rid the empire from his work and imagery. Sennacherib's efforts led to Sargon only rarely being mentioned in later texts. When modern Assyriology took form in Western Europe in the 18th century, historians mainly followed the writings of classical Greco-Roman authors and the descriptions of Assyria in the Hebrew Bible for information. Given that Sargon is barely mentioned in either, he was consequently forgotten, the then prevalent historical reconstructions placing Sennacherib as the direct successor of Sargon's predecessor Shalmaneser V and identifying Sargon as an alternate name for one of the more well-known kings.