The early policies of Mexico toward her Texas colonists had been extremely liberal. Large grants of land were made to them, and no taxes or duties imposed. The relationship between the Anglo-Americans and Mexicans was cordial. But, following a series of revolutions begun in 1829, unscrupulous rulers successively seized power in Mexico. Their unjust acts and despotic decrees led to the revolution in Texas.

In June, 1832, the colonists forced the Mexican authorities at Anahuac to release Wm. B. Travis and others from unjust imprisonment. The Battle of Velasco, June 26, and the Battle of Nacogdoches, August 2, followed; in both the Texans were victorious. Stephen Fuller Austin, "Father of Texas", was arrested January 3, 1834, and held in Mexico without trial until July, 1835. The Texans formed an army, and on November 12, 1835, established a provisional government.

The first shot of the Revolution of 1835-36 was fired by the Texans at Gonzales, October 2, 1835, in resistance to a demand by Mexican soldiers for a small cannon held by the colonists. The Mexican garrison at Goliad fell October 9; the Battle of Concepcion was won by the Texans, October 28. San Antonio was captured December 10, 1835 after five days of fighting in which the indomitable Benjamin R. Milam died a hero, and the Mexican Army evacuated Texas.

Texas declared her independence at Washington-on-the-Brazos March 2. For nearly two months her armies met disaster and defeat: Dr. James Grant's men were killed on the Aguadulce March 2; William Barret Travis and his men sacrificed their lives at the Alamo, March 6; William Ward was defeated at Refugio, March 14; Amos B. King's men were executed near Refugio, March 16; and James Walker Fannin and his army were put to death near Goliad March 27, 1836.

On this field on April 21, 1836 the Army of Texas commanded by General Sam Houston, and accompanied by the Secretary of War, Thomas J. Rusk, attacked the larger invading army of Mexicans under General Santa Anna. The battle line from left to right was formed by Sidney Sherman's regiment, Edward Burleson's regiment, the artillery commanded by George W. Hockley, Henry Millard's infantry and the cavalry under Mirabeau B. Lamar. Sam Houston led the infantry charge.

With the battle cry, "Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!" the Texans charged. The enemy, taken by surprise, rallied for a few minutes then fled in disorder. The Texans had asked no quarter and gave none. The slaughter was appalling, victory complete, and Texas free! On the following day General Antonio Lopez De Santa Anna, self-styled "Napoleon of the West", received from a generous foe the mercy he had denied Travis at the Alamo and Fannin at Goliad.

Citizens of Texas and immigrant soldiers in the Army of Texas at San Jacinto were natives of Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Austria, Canada, England, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Poland, Portugal and Scotland.

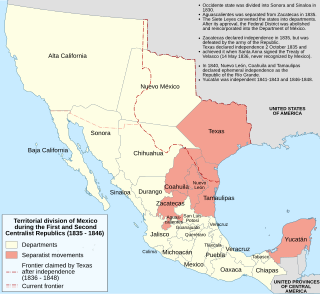

Measured by its results, San Jacinto was one of the decisive battles of the world. The freedom of Texas from Mexico won here led to annexation and to the Mexican–American War, resulting in the acquisition by the United States of the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma. Almost one-third of the present area of the American Nation, nearly a million square miles of territory, changed sovereignty.