Alcaeus of Mytilene was a lyric poet from the Greek island of Lesbos who is credited with inventing the Alcaic stanza. He was included in the canonical list of nine lyric poets by the scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria. He was a contemporary of Sappho, with whom he may have exchanged poems. He was born into the aristocratic governing class of Mytilene, the main city of Lesbos, where he was involved in political disputes and feuds.

Sappho was an Archaic Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by music. In ancient times, Sappho was widely regarded as one of the greatest lyric poets and was given names such as the "Tenth Muse" and "The Poetess". Most of Sappho's poetry is now lost, and what is extant has mostly survived in fragmentary form; only the Ode to Aphrodite is certainly complete. As well as lyric poetry, ancient commentators claimed that Sappho wrote elegiac and iambic poetry. Three epigrams formerly attributed to Sappho are extant, but these are actually Hellenistic imitations of Sappho's style.

Alcman was an Ancient Greek choral lyric poet from Sparta. He is the earliest representative of the Alexandrian canon of the Nine Lyric Poets. He wrote six books of choral poetry, most of which is now lost; his poetry survives in quotation from other ancient authors and on fragmentary papyri discovered in Egypt. His poetry was composed in the local Doric dialect with Homeric influences. Based on his surviving fragments, his poetry was mostly hymns, and seems to have been composed in long stanzas made up of lines in several different meters.

Praxilla, was a Greek lyric poet of the 5th century BC from Sicyon on the Gulf of Corinth. Five quotations attributed to Praxilla and three paraphrases from her poems survive. The surviving fragments attributed to her come from both religious choral lyric and drinking songs (skolia); the three paraphrases are all versions of myths. Various social contexts have been suggested for Praxilla based on this range of surviving works. These include that her poetry was in fact composed by two different authors, that Praxilla was a hetaira (courtesan), that she was a professional musician, or that the drinking songs derive from a non-elite literary tradition rather than being authored by a single writer.

Anactoria is a woman mentioned by the Ancient Greek poet Sappho, who wrote in the late seventh and early sixth centuries BCE. Sappho names Anactoria as the object of her desire in a poem numbered as fragment 16. Another poem by Sappho, fragment 31, is traditionally called the "Ode to Anactoria", though no name appears in it. As portrayed in Sappho's work, she is likely to have been a young, aristocratic follower of Sappho's, of marriageable age. It is possible that fragment 16 was written in connection with her wedding to an unknown man. The name "Anactoria" has also been argued to have been a pseudonym, perhaps of a woman named Anagora from Miletus, or an archetypal creation of Sappho's imagination.

Greek and Latin metre is an overall term used for the various rhythms in which Greek and Latin poems were composed. The individual rhythmical patterns used in Greek and Latin poetry are also known as "metres".

Aeolic verse is a classification of Ancient Greek lyric poetry referring to the distinct verse forms characteristic of the two great poets of Archaic Lesbos, Sappho and Alcaeus, who composed in their native Aeolic dialect. These verse forms were taken up and developed by later Greek and Roman poets and some modern European poets.

Sappho 31 is an archaic Greek lyric poem by the ancient Greek poet Sappho of the island of Lesbos. The poem is also known as phainetai moi after the opening words of its first line. It is one of Sappho's most famous poems, describing her love for a young woman.

Sappho 16 is a fragment of a poem by the archaic Greek lyric poet Sappho. It is from Book I of the Alexandrian edition of Sappho's poetry, and is known from a second-century papyrus discovered at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt at the beginning of the twentieth century. Sappho 16 is a love poem – the genre for which Sappho was best known – which praises the beauty of the narrator's beloved, Anactoria, and expresses the speaker's desire for her now that she is absent. It makes the case that the most beautiful thing in the world is whatever one desires, using Helen of Troy's elopement with Paris as a mythological exemplum to support this argument. The poem is at least 20 lines long, though it is uncertain whether the poem ends at line 20 or continues for another stanza.

Sappho 44 is a fragment of a poem by the archaic Greek poet Sappho, which describes the wedding of Hector and Andromache. Preserved on a piece of papyrus found in Egypt, it is the longest of Sappho's surviving fragments, and is written in epic style suiting its subject. The metre is glyconic with double dactylic expansion.

Greek lyric is the body of lyric poetry written in dialects of Ancient Greek. It is primarily associated with the early 7th to the early 5th centuries BC, sometimes called the "Lyric Age of Greece", but continued to be written into the Hellenistic and Imperial periods.

The Ode to Aphrodite is a lyric poem by the archaic Greek poet Sappho, who wrote in the late seventh and early sixth centuries BCE, in which the speaker calls on the help of Aphrodite in the pursuit of a beloved. The poem survives in almost complete form, with only two places of uncertainty in the text, preserved through a quotation from Dionysius of Halicarnassus' treatise On Composition and in fragmentary form in a scrap of papyrus discovered at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt.

The Brothers Poem or Brothers Song is a series of lines of verse attributed to the archaic Greek poet Sappho, which had been lost since antiquity until being rediscovered in 2014. Most of its text, apart from its opening lines, survives. It is known only from a papyrus fragment, comprising one of a series of poems attributed to Sappho. It mentions two of her brothers, Charaxos and Larichos; the only known mention of their names in Sappho's writings, though they are known from other sources. These references, and aspects of the language and style, have been used to establish her authorship.

The midnight poem is a fragment of Greek lyric poetry preserved by Hephaestion. It is possibly by the archaic Greek poet Sappho, and is fragment 168 B in Eva-Maria Voigt's edition of her works. It is also sometimes known as PMG fr. adesp. 976 – that is, fragment 976 from Denys Page's Poetae Melici Graeci, not attributed to any author. The poem, four lines describing a woman alone at night, is one of the best-known surviving pieces of Greek lyric poetry. Long thought to have been composed by Sappho, it is one of the most frequently translated and adapted of the works ascribed to her.

The Tithonus poem, also known as the old age poem or the New Sappho, is a poem by the archaic Greek poet Sappho. It is part of fragment 58 in Eva-Maria Voigt's edition of Sappho. The poem is from Book IV of the Alexandrian edition of Sappho's poetry. It was first published in 1922, after a fragment of papyrus on which it was partially preserved was discovered at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt; further papyrus fragments published in 2004 almost completed the poem, drawing international media attention. One of very few substantially complete works by Sappho, it deals with the effects of ageing. There is scholarly debate about where the poem ends, as four lines previously thought to have been part of the poem are not found on the 2004 papyrus.

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1231 is a papyrus discovered at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, first published in 1914 by Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt. The papyrus preserves fragments of the second half of Book I of a Hellenistic edition of the poetry of the archaic poet Sappho.

Sappho 94, sometimes known as Sappho's Confession, is a fragment of a poem by the archaic Greek poet Sappho. The poem is written as a conversation between Sappho and a woman who is leaving her, perhaps in order to marry, and describes a series of memories of their time together. It survives on a sixth-century AD scrap of parchment. Scholarship on the poem has focused on whether the initial surviving lines of the poem are spoken by Sappho or the departing woman, and on the interpretation of the eighth stanza, possibly the only mention of homosexual activities in the surviving Sapphic corpus.

Sappho 2 is a fragment of a poem by the archaic Greek lyric poet Sappho. In antiquity it was part of Book I of the Alexandrian edition of Sappho's poetry. Sixteen lines of the poem survive, preserved on a potsherd discovered in Egypt and first published in 1937 by Medea Norsa. It is in the form of a hymn to the goddess Aphrodite, summoning her to appear in a temple in an apple grove. The majority of the poem is made up of an extended description of the sacred grove to which Aphrodite is being summoned.

Sappho was an ancient Greek lyric poet from the island of Lesbos. She wrote around 10,000 lines of poetry, only a small fraction of which survives. Only one poem is known to be complete; in some cases as little as a single word survives. Modern editions of Sappho's poetry are the product of centuries of scholarship, first compiling quotations from surviving ancient works, and from the late 19th century rediscovering her works preserved on fragments of ancient papyri and parchment. Along with the poems which can be attributed with confidence to Sappho, a small number of surviving fragments in her Aeolic dialect may be by either her or her contemporary Alcaeus. Modern editions of Sappho also collect ancient "testimonia" which discuss Sappho's life and works.

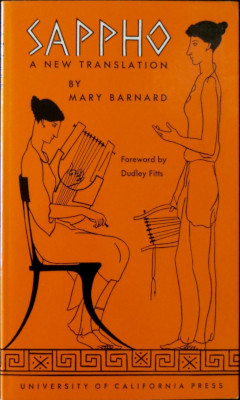

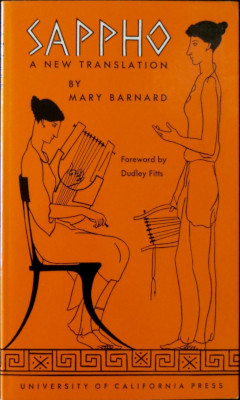

Sappho: A New Translation is a 1958 book by Mary Barnard with a foreword by Dudley Fitts. Inspired by Salvatore Quasimodo's Lirici Greci and encouraged by Ezra Pound, with whom Barnard had corresponded since 1933, she translated 100 poems of the archaic Greek poet Sappho into English free verse. Though some early reviewers criticised Barnard's choice not to use a more structured meter, her translation was both commercially and critically successful, and her work has inspired subsequent translators of Sappho's poetry.