Published around 30 BCE, the second book of Satires is a series of poems composed in dactylic hexameter by the Roman poet Horace. Satires 2.5 [1] stands out in the work for its unique analysis of legacy hunting.

Published around 30 BCE, the second book of Satires is a series of poems composed in dactylic hexameter by the Roman poet Horace. Satires 2.5 [1] stands out in the work for its unique analysis of legacy hunting.

Horace's Satire Book II, Satire V is poem about a discussion between Ulysses and Tiresias that is presented as a continuation of their interaction in the underworld in Book 11 of Homer's Odyssey . Ulysses is concerned that he will have no wealth once he returns to Ithaca because the suitors will have squandered the contents of his storehouses. Stating bluntly that breeding and character are meaningless without wealth, he asks Tiresias for any suggestions on how to rebuild his prosperity. Tiresias suggests that Ulysses try his hand at legacy hunting, and gives examples of characters through history that have ingratiated themselves with the affluent in order to be named as benefactors in their will. Despite Ulysses’ skepticism, Tiresias asserts the plan's merit and provides examples of how to curry favor.

The structure of the poem places the majority of focus on section C, especially the story of Nasica and Coranus. [3] The poem draws from the imagery of hunting, referring to the legacy-seeker as adept with snares and to his prey as an unwary tunny fish. Most importantly, in the poem “nothing suggests that the typical senex has a mind or will of his own.”. [4] The victim is utterly objectified and reduced to a feeble creature that the captator can exploit.

On a linguistic level, the poem features very colloquial and expressive language. “‘breeding and character without assets are vilior alga--more worthless than seaweed.’ Tell me, says Ulysses, how I can rake together ‘piles of cash’-- aeris acervos.”. [5] The analogies in the text are similarly graphic, as in the story of the over-insistent heir in Thebes who was required by the will of his benefactor to carry her oil-soaked slippery carcass on his shoulders during the funeral procession.

Satire 2.5 is often thought of as the least “Horatian” of the Satires and is often compared to works by Juvenal, a poet of the 1st century AD. Juvenal’s poems focus on the perversions of man and hint at Man’s loss of “his highest potentialities”. [6] [7] Many scholars acknowledge this cynicism in Satire 2.5 and see a connection between the two authors. As Shackleton Bailey writes, “Uniquely for Horace, it concerns a particular social malpractice (touting for legacies), and its mordant humour has reminded many readers of Juvenal.” [8]

Horace diverges from classical portrayals of Ulysses in this satire. Ulysses is a heroic Greek protagonist, but in this poem he eschews the importance of noble bearing in favor of temporal riches. Michael Roberts writes that “the theme of perversion of human values runs throughout the satire,” [9] and this is especially relevant to the destitute Ulysses. Horace’s choice of an established epic hero to request Tiresias’ scheming advice displays a distortion of Greek heroic values. The poem also distorts the meaning of xenia, reducing the powerful bonds of host-guest friendship down to a calculated exchange of flattery for services. Although Ulysses is mostly silent after line 23, it is implied that he has been swayed by the pragmatism of Tiresias’ words.

Horace’s characterization of Tiresias is strikingly different from other authors. Instead of portraying him as a great prophet, Horace characterizes him as a shady figure, quick to reveal the secret to making money. With this, the characterization of Tiresias creates a moral tension between the paragon prophet so highly respected in ancient literature and the shady truth-teller that reveals the inner workings of legacy hunting. It is from this tension that the satirical nature of the work is derived. [10]

Horace also takes a noticeably different tack than other Roman and Greek poets with regard to his characterization of Penelope. Horace introduces her first as the virtuous wife she is typically characterized as in lines 77-78. Ulysses claims that his chaste wife would never betray their vows of monogamy, but Tiresias counters that she is chaste only because the suitors are more motivated by consuming Ulysses’ bountiful stores than by sex.

Penelope, classically a bastion of chastity, is hereby portrayed as corruptible like any other woman.

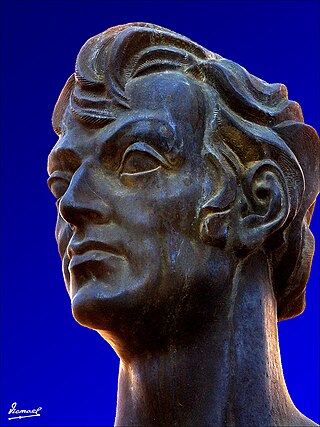

Quintus Horatius Flaccus, commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his Odes as just about the only Latin lyrics worth reading: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words."

The Satires are a collection of satirical poems by the Latin author Juvenal written between the end of the first and the early second centuries A.D.

Penelope is a character in Homer's Odyssey. She was the queen of Ithaca and was the daughter of Spartan king Icarius and Asterodia. Penelope is known for her fidelity to her husband Odysseus, despite the attention of more than a hundred suitors during his absence. In one source, Penelope's original name was Arnacia or Arnaea.

Publius Papinius Statius was a Greco-Roman poet of the 1st century CE. His surviving Latin poetry includes an epic in twelve books, the Thebaid; a collection of occasional poetry, the Silvae; and an unfinished epic, the Achilleid. He is also known for his appearance as a guide in the Purgatory section of Dante's epic poem, the Divine Comedy.

Marcus Valerius Martialis was a Roman poet born in Hispania best known for his twelve books of Epigrams, published in Rome between AD 86 and 103, during the reigns of the emperors Domitian, Nerva and Trajan. In these poems he satirises city life and the scandalous activities of his acquaintances, and romanticises his provincial upbringing. He wrote a total of 1,561 epigrams, of which 1,235 are in elegiac couplets.

Aulus Persius Flaccus was a Roman poet and satirist of Etruscan origin. In his works, poems and satires, he shows a Stoic wisdom and a strong criticism for what he considered to be the stylistic abuses of his poetic contemporaries. His works, which became very popular in the Middle Ages, were published after his death by his friend and mentor, the Stoic philosopher Lucius Annaeus Cornutus.

Absalom and Achitophel is a celebrated satirical poem by John Dryden, written in heroic couplets and first published in 1681. The poem tells the Biblical tale of the rebellion of Absalom against King David; in this context it is an allegory used to represent a story contemporary to Dryden, concerning King Charles II and the Exclusion Crisis (1679–1681). The poem also references the Popish Plot (1678).

Gaius Lucilius was the earliest Roman satirist, of whose writings only fragments remain. A Roman citizen of the equestrian class, he was born at Suessa Aurunca in Campania, and was a member of the Scipionic Circle.

The Achilleid is an unfinished epic poem by Publius Papinius Statius that was intended to present the life of Achilles from his youth to his death at Troy. Only about one and a half books were completed before the poet's death. What remains is an account of the hero's early life with the centaur Chiron, and an episode in which his mother, Thetis, disguised him as a girl on the island of Scyros, before he joined the Greek expedition against Troy.

Satire VI is the most famous of the sixteen Satires by the Roman author Juvenal written in the late 1st or early 2nd century. In English translation, this satire is often titled something in the vein of Against Women due to the most obvious reading of its content. It enjoyed significant social currency from late antiquity to the early modern period, being read as a proof-text for a wide array of misogynistic beliefs. Its current significance rests in its role as a crucial body of evidence on Roman conceptions of gender and sexuality.

The Telegony is a lost ancient Greek epic poem about Telegonus, son of Odysseus by Circe. His name is indicative of his birth on Aeaea, far from Odysseus' home of Ithaca. It was part of the Epic Cycle of poems that recounted the myths of the Trojan War as well as the events that led up to and followed it. The story of the Telegony comes chronologically after that of the Odyssey and is the final episode in the Epic Cycle. The poem was sometimes attributed in antiquity to Cinaethon of Sparta, but in one source it is said to have been stolen from Musaeus by Eugamon or Eugammon of Cyrene. The poem comprised two books of verse in dactylic hexameter.

The Thebaid is a Latin epic poem written by the Roman poet Statius. Published in the early 90s AD, it contains 12 books and recounts the clash of two brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, over the throne of the Greek city of Thebes. After Polynices is sent into exile, he forges an alliance of seven Greek princes and embarks on a military campaign against his brother.

Righteous indignation, also called righteous anger, is anger that is primarily motivated by a perception of injustice or other profound moral lapse. It is distinguished from anger that is prompted by something more personal, like an insult.

Decimus Junius Juvenalis, known in English as Juvenal, was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the Satires. The details of Juvenal's life are unclear, although references within his text to known persons of the late first and early second centuries CE fix his earliest date of composition. One recent scholar argues that his first book was published in 100 or 101. A reference to a political figure dates his fifth and final surviving book to sometime after 127.

The Satires is a collection of satirical poems written in Latin dactylic hexameters by the Roman poet Horace. Published probably in 35 BC and at the latest, by 33 BC, the first book of Satires represents Horace's first published work. It established him as one of the great poetic talents of the Augustan Age. The second book was published in 30 BC as a sequel.

London is a poem by Samuel Johnson, produced shortly after he moved to London. Written in 1738, it was his first major published work. The poem in 263 lines imitates Juvenal's Third Satire, expressed by the character of Thales as he decides to leave London for Wales. Johnson imitated Juvenal because of his fondness for the Roman poet and he was following a popular 18th-century trend of Augustan poets headed by Alexander Pope that favoured imitations of classical poets, especially for young poets in their first ventures into published verse.

The Vanity of Human Wishes: The Tenth Satire of Juvenal Imitated is a poem by the English author Samuel Johnson. It was written in late 1748 and published in 1749. It was begun and completed while Johnson was busy writing A Dictionary of the English Language and it was the first published work to include Johnson's name on the title page.

Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? is a Latin phrase found in the Satires, a work of the 1st–2nd century Roman poet Juvenal. It may be translated as "Who will guard the guards themselves?" or "Who will watch the watchmen?".

Paul Whitehead (1710–1774) was a British satirist and a secretary to the infamous Hellfire Club.

William James Niall Rudd was an Irish-born British classical scholar.