Usages

1st century

- Horace

The original use of the phrase Sapere aude appears in the First Book of Letters (20 BC), by the Roman poet Horace; in the second letter, addressed to Lolius, in line 40, the passage is: Dimidium facti, qui coepit, habet; sapere aude, incipe. ("He who has begun is half done; dare to know; begin!")

The phrase is the moral to a story in which a fool waits for a stream to cease flowing, before attempting to cross it. In saying, "He who begins is half done. Dare to know, begin!", Horace suggests the value of human endeavour, of persistence in reaching a goal, of the need for effort to overcome obstacles. Moreover, the laconic Latin of Sapere aude also can be loosely translated as the English phrase "Dare to be wise".

4th century

- Augustine

Augustine of Hippo quotes Horace's maxim in his early philosophical dialogue De quantitate animae, [2] 23.41, telling his interlocutor Evodius not to be afraid of questioning his teaching on the capabilities of the soul:

Noli nimis ex auctoritate pendere, praesertim mea quae nulla est; et quod ait Horatius: 'Sapere aude', ne non te ratio subiuget priusquam metus.

"Don't rely so much on authority, especially on mine, which is null. There is also that saying from Horace: 'Dare to be wise!', so that fear may not subdue you more than reason does."

16th century

- Philip Melanchthon

In his inaugural address as Professor of Greek in Wittenberg on August 29, 1518, Philip Melanchthon quoted Horace's letter. [3]

18th century

- Immanuel Kant

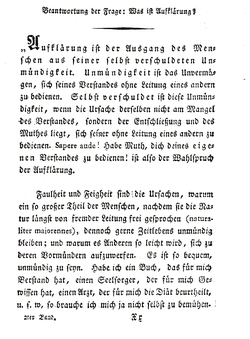

In the essay, "Answering the Question: What Is Enlightenment?" (1784), Immanuel Kant describes the Age of Enlightenment as "Man's release from his self-incurred immaturity"; and, with the phrase Sapere aude, the philosopher charges the reader to follow such a program of intellectual self-liberation, by means of Reason. The essay is Kant's shrewd, political challenge to men and women, suggesting that the mass of "domestic cattle" have been bred, by unfaithful stewards, to not question what they have been told about the world and its ways.

Kant classifies the uses of reason as public and private. The public use of reason is discourse in the public sphere, such as political discourse (argument and analysis); the private use of reason is rational argument, such as that used by a person entrusted with a duty, either official or organizational. Skillfully praising King Frederick II of Prussia (r. 1740–86) for his intellectual receptiveness to the political, social, and cultural ideas of the Enlightenment, the philosopher Kant proposes that an enlightened prince is one who instructs his subjects to: "Argue as much as you will, and about what you will, only obey!"

It is the courage of the individual man to abide the advice Sapere aude that will break the shackles of despotism, and reveal, through public discourse, for the benefit of the mass population and of the State, better methods of governance, and of legitimate complaint. [4]

19th century

The founder of homeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann, used the phrase on the cover of his Organon of Medicine (various editions in 1810, 1819, 1824, 1829, 1833 and 1922).

In 1869 the newly-founded University of Otago [5] in Dunedin chose the phrase as their motto.

20th century

- Michel Foucault

In response to Immanuel Kant's Age of Enlightenment propositions for intellectual courage, in the essay "What is Enlightenment?" (1984), Michel Foucault rejected much of the hopeful politics proposed by Kant: a people ruled by just rulers; ethical leaders inspired by the existential dare advised in the phrase Sapere aude. Instead, Foucault applied ontology to examine the innate resources for critical thinking of a person's faculty of Reason. With the analytical value of Sapere aude reinforced by the concept of "Faithful betrayal" to impracticable beliefs, Foucault disputed the Enlightenment-era arguments that Kant presents in the essay "Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment?" (1784).

Like his 18th-century predecessor, Foucault also based his philosophic interpretation of Sapere aude upon a definite practice of critical thinking that is an "attitude, an ethos, a philosophical life in which [is found] the critique of what we are". Such an enlightened, intellectual attitude applies reason to experience, and so effects a historical criticism of "the limits that are imposed on us". The criticism is "an experiment with the possibility of going beyond" imposed limits, in order to reach the limit-experience, which simultaneously is an individual, personal act, and an act that breaks the concept of the individual person. [6]

Vincent Massey choose the phrase Sapere aude as the motto of Massey College in Toronto that the Massey foundation established in 1963 as residential college, a self-governing unit of the University of Toronto.