In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empiricists argue that empiricism is a more reliable method of finding the truth than purely using logical reasoning, because humans have cognitive biases and limitations which lead to errors of judgement. Empiricism emphasizes the central role of empirical evidence in the formation of ideas, rather than innate ideas or traditions. Empiricists may argue that traditions arise due to relations of previous sensory experiences.

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification", often in contrast to other possible sources of knowledge such as faith, tradition, or sensory experience. More formally, rationalism is defined as a methodology or a theory "in which the criterion of truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive".

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa, which refers to philosophy as well as logic, mathematics, and physics; and Kalam, which refers to a rationalist form of Scholastic Islamic theology which includes the schools of Maturidiyah, Ashaira and Mu'tazila.

Nous, from Greek: νοῦς, is a concept from classical philosophy, sometimes equated to intellect or intelligence, for the faculty of the human mind necessary for understanding what is true or real.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to metaphysics:

Common sense is "knowledge, judgement, and taste which is more or less universal and which is held more or less without reflection or argument". As such, it is often considered to represent the basic level of sound practical judgement or knowledge of basic facts that any adult human being ought to possess. It is "common" in the sense of being shared by nearly all people. The everyday understanding of common sense is ultimately derived from historical philosophical discussions. Relevant terms from other languages used in such discussions include Latin sensus communis, Ancient Greek κοινὴ αἴσθησις, and French bon sens. However, these are not straightforward translations in all contexts, and in English different shades of meaning have developed. In philosophical and scientific contexts, since the Age of Enlightenment the term "common sense" has been used for rhetorical effect both approvingly and disapprovingly. On the one hand it has been a standard for good taste, good sense, and source of scientific and logical axioms. On the other hand it has been equated to conventional wisdom, vulgar prejudice, and superstition.

Philosophy in Malta refers to the philosophy of Maltese nationals or those of Maltese descent, whether living in Malta or abroad, whether writing in their native Maltese language or in a foreign language. Though Malta is not more than a tiny European island in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, for the last six centuries its very small population happened to come in close contact with some of Europe's main political, academic and intellectual movements. Philosophy was among the interests fostered by its academics and intellectuals.

Maximilian Balzan (1637–1711) was a minor Maltese mediaeval philosopher who specialised mainly in physics and art. He was also an accomplished theologian. He had a very successful administrative career, both in the civil as well as the ecclesiastical sphere, and he further gave a significant share in academic circles.

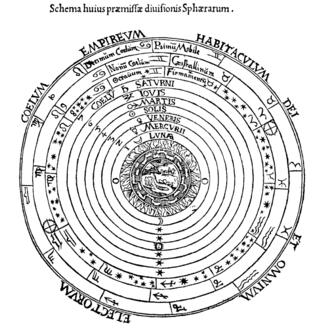

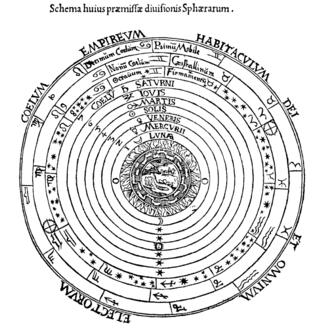

Constance Vella (1687–1759) was a major Maltese philosopher who specialised mainly in physics, logic, cosmology, and metaphysics. Vella's speciality is that, despite being a Scholastic, he was not an Aristotelic-Thomist one, but rather an Aristotelic-Scotist philosopher, that is more in the line of John Duns Scotus.

Stefano Pace (1695–1735) was a minor Maltese mediaeval philosopher who specialised mainly in physics.

Joseph Demarco (1718–1793) was a Maltese medical practitioner, a scientist, and a major philosopher. His areas of specialisation in philosophy were mostly philosophical psychology and physiology.

Justus Azzopardi was a Maltese philosopher. His area of specialisation in philosophy was mainly metaphysics. No portrait of him is known to exist.

Gaetanus Matthew Perez was a minor Maltese philosopher. His area of specialisation in philosophy was chiefly ethics. No portrait of Perez is known to exist so far.

Francis Saviour Farrugia was a minor Maltese philosopher, doctor of law, and legislator. He specialised in jurisprudence.

George Caruana (1831–1872) was a Maltese minor philosopher mostly interested in epistemology. He held the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Malta (1859–72).

Aloisio Galea (1851–1905) was a Maltese theologian and minor philosopher. He specialised mostly in moral philosophy.

Peter Paul Borg (1843–1934) was a Maltese theologian, canonist and minor philosopher. He was mostly interested in the philosophy of law.

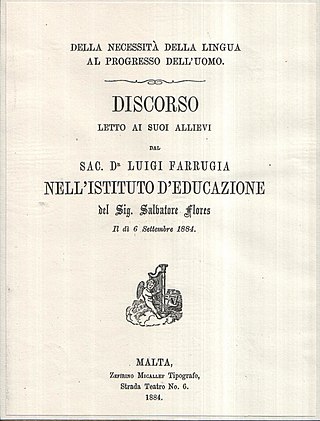

Louis Farrugia (1857–1933) was a Maltese theologian and minor philosopher. In philosophy he was mostly interested in Scholasticism and literature. No portrait of him has been identified up till now.

John Formosa (1869–1941) was a Maltese theologian, canonist, minor philosopher, and poet. In philosophy he mostly specialised in metaphysics.

Anastastio Cuschieri (1876–1962) was a Maltese poet, politician, and minor philosopher. He held the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Malta (1901–39). In philosophy he was mostly interested in ethics.