Pietru Caxaro or Caxaru, also known in English as Peter Caxaro, was a Maltese philosopher and poet. He is so far Malta's first known philosopher, fragments of whose works are extant. His philosophical views and positions qualify him as an honourable adherent of the mediaeval humanist movement. His contribution skilfully stands as a mature reflection of the social and cultural revival of his time.

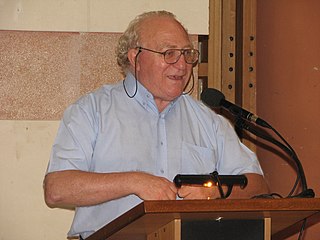

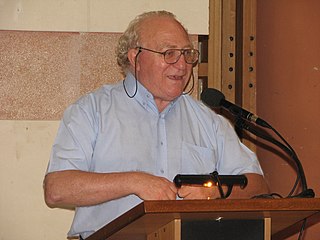

Peter Serracino Inglott was a Priest, Philosopher, Scholar and Rector of the University of Malta from 1987 to 1988, then consecutively from 1991 to 1996. He was awarded the title of Emeritus Professor of philosophy at the University of Malta. He was a key figure at reconstructing the Maltese education system and held academia to his personal life prominently. He was also politically affiliated with the country's Nationalist Party, serving as advisor to former Prime Minister of Malta, Eddie Fenech Adami.

Saverius Pace was a minor Maltese philosopher who specialised in physics.

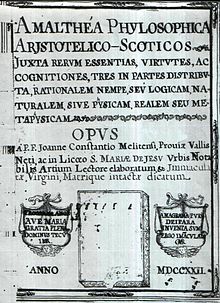

Constance Vella (1687–1759) was a major Maltese philosopher who specialised mainly in physics, logic, cosmology, and metaphysics. Vella's speciality is that, despite being a Scholastic, he was not an Aristotelic-Thomist one, but rather an Aristotelic-Scotist philosopher, that is more in the line of John Duns Scotus.

John Constance Parnis (1695–1735) was a major Maltese mediaeval philosopher who specialised mainly in metaphysics, physics, and logic.

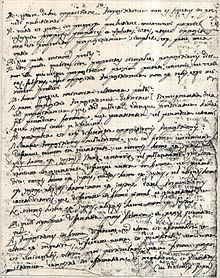

Nicholas Zammit (1815–1899) was a Maltese medical doctor, an architect, an artistic designer, and a major philosopher. His area of specialisation in philosophy was chiefly ethics. Throughout his philosophical career he did not adhere to just one intellectual position. Roughly two-thirds into his life, Zammit passed from a liberal way of thinking to a conservative one. This does not mean that there are no carry-overs, developments, or continuations between the two phases, or that Zammit himself acknowledged such a division. Notwithstanding, the development suggests that an analysis of Zammit's works will reveal different attitudes, dispositions, emphasis, and conclusions of the two periods.

Mario Vella is a Maltese philosopher, economist and politician. He was Governor of the Central Bank of Malta from 2016 to 2020.

Justus Azzopardi was a Maltese philosopher. His area of specialisation in philosophy was mainly metaphysics. No portrait of him is known to exist.

Francis Saviour Farrugia was a minor Maltese philosopher, doctor of law, and legislator. He specialised in jurisprudence.

Jerome Inglott (1776–1835) was a Maltese philosopher and theologian. His areas of specialisation in philosophy were chiefly metaphysics and ontology. He held the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Malta (1822–27), and was one of the Philosopher-Rectors at the same university (1826–33).

Dominic Pace (1851–1907) was a Maltese theologian and minor philosopher. In philosophy he mostly specialised in Aristotelico-Thomist Scholasticism.

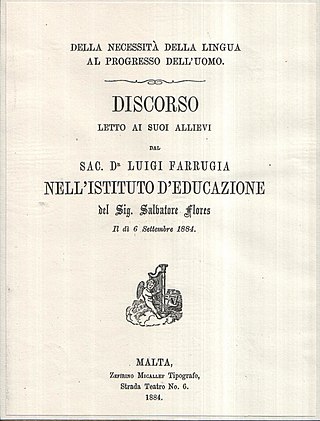

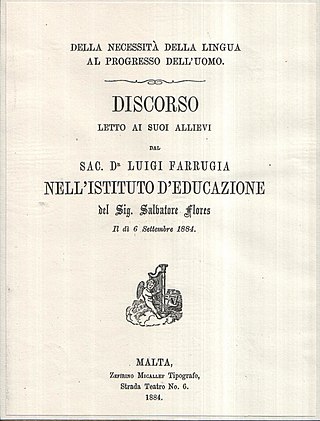

Louis Farrugia (1857–1933) was a Maltese theologian and minor philosopher. In philosophy he was mostly interested in Scholasticism and literature. No portrait of him has been identified up till now.

John Formosa (1869–1941) was a Maltese theologian, canonist, minor philosopher, and poet. In philosophy, he mostly specialised in metaphysics.

Daniel Callus (1888–1965) was a Maltese historian and philosopher. His main interest was in the history of Medieval philosophy.

John Micallef (1923–2003) was a Maltese philosopher. Although his thoughts remained philosophically grounded in the Christian tradition, he was primarily interested in existentialism.

Salvino Busuttil was a Maltese economist, ambassador to France, and philosopher. In philosophy he specialised in economics and international relations.

Oliver Friggieri was a Maltese poet, novelist, literary critic, and philosopher. He led the establishment of literary history and criticism in Maltese while teaching at the University of Malta, studying the works of Dun Karm, Rużar Briffa, and others. A prolific writer himself, Friggieri explored new genres to advocate the Maltese language, writing the libretti for the first oratorio and the first cantata in Maltese. His work aimed to promote the Maltese cultural identity, while not shying from criticism: one of his most famous novels, Fil-Parlament Ma Jikbrux Fjuri, attacked the tribalistic divisions of society caused by politics. From philosophy, he was mostly interested in epistemology and existentialism.

Vincent Riolo is a Maltese philosopher mostly interested and specialised in logic and the philosophy of language.

Michael Zammit is a Maltese philosopher, specialised in Ancient and Eastern philosophy.

Mark Montebello is a Maltese philosopher and author. He is mostly known for his controversies with Catholic Church authorities but also for his classic biographies of Manuel Dimech and Dom Mintoff.