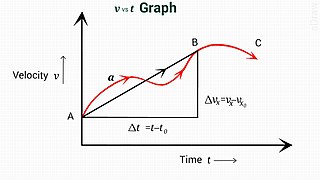

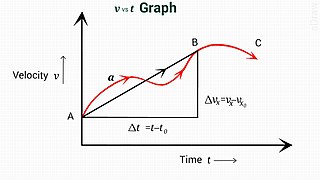

In physics, equations of motion are equations that describe the behavior of a physical system in terms of its motion as a function of time. More specifically, the equations of motion describe the behavior of a physical system as a set of mathematical functions in terms of dynamic variables. These variables are usually spatial coordinates and time, but may include momentum components. The most general choice are generalized coordinates which can be any convenient variables characteristic of the physical system. The functions are defined in a Euclidean space in classical mechanics, but are replaced by curved spaces in relativity. If the dynamics of a system is known, the equations are the solutions for the differential equations describing the motion of the dynamics.

Kinematics is a subfield of physics and mathematics, developed in classical mechanics, that describes the motion of points, bodies (objects), and systems of bodies without considering the forces that cause them to move. Kinematics, as a field of study, is often referred to as the "geometry of motion" and is occasionally seen as a branch of both applied and pure mathematics since it can be studied without considering the mass of a body or the forces acting upon it. A kinematics problem begins by describing the geometry of the system and declaring the initial conditions of any known values of position, velocity and/or acceleration of points within the system. Then, using arguments from geometry, the position, velocity and acceleration of any unknown parts of the system can be determined. The study of how forces act on bodies falls within kinetics, not kinematics. For further details, see analytical dynamics.

In science, work is the energy transferred to or from an object via the application of force along a displacement. In its simplest form, for a constant force aligned with the direction of motion, the work equals the product of the force strength and the distance traveled. A force is said to do positive work if it has a component in the direction of the displacement of the point of application. A force does negative work if it has a component opposite to the direction of the displacement at the point of application of the force.

Noether's theorem states that every continuous symmetry of the action of a physical system with conservative forces has a corresponding conservation law. This is the first of two theorems published by mathematician Emmy Noether in 1918. The action of a physical system is the integral over time of a Lagrangian function, from which the system's behavior can be determined by the principle of least action. This theorem only applies to continuous and smooth symmetries of physical space.

In physics, Hamiltonian mechanics is a reformulation of Lagrangian mechanics that emerged in 1833. Introduced by Sir William Rowan Hamilton, Hamiltonian mechanics replaces (generalized) velocities used in Lagrangian mechanics with (generalized) momenta. Both theories provide interpretations of classical mechanics and describe the same physical phenomena.

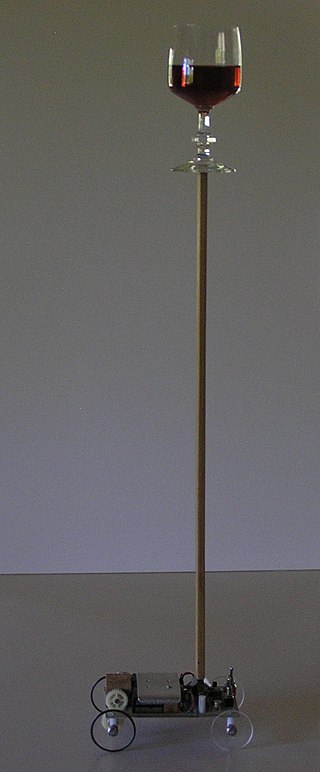

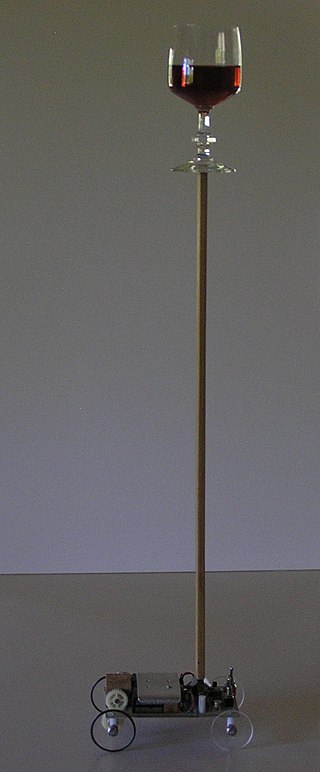

An inverted pendulum is a pendulum that has its center of mass above its pivot point. It is unstable and falls over without additional help. It can be suspended stably in this inverted position by using a control system to monitor the angle of the pole and move the pivot point horizontally back under the center of mass when it starts to fall over, keeping it balanced. The inverted pendulum is a classic problem in dynamics and control theory and is used as a benchmark for testing control strategies. It is often implemented with the pivot point mounted on a cart that can move horizontally under control of an electronic servo system as shown in the photo; this is called a cart and pole apparatus. Most applications limit the pendulum to 1 degree of freedom by affixing the pole to an axis of rotation. Whereas a normal pendulum is stable when hanging downward, an inverted pendulum is inherently unstable, and must be actively balanced in order to remain upright; this can be done either by applying a torque at the pivot point, by moving the pivot point horizontally as part of a feedback system, changing the rate of rotation of a mass mounted on the pendulum on an axis parallel to the pivot axis and thereby generating a net torque on the pendulum, or by oscillating the pivot point vertically. A simple demonstration of moving the pivot point in a feedback system is achieved by balancing an upturned broomstick on the end of one's finger.

In theoretical physics and mathematical physics, analytical mechanics, or theoretical mechanics is a collection of closely related formulations of classical mechanics. Analytical mechanics uses scalar properties of motion representing the system as a whole—usually its kinetic energy and potential energy. The equations of motion are derived from the scalar quantity by some underlying principle about the scalar's variation.

In analytical mechanics, generalized coordinates are a set of parameters used to represent the state of a system in a configuration space. These parameters must uniquely define the configuration of the system relative to a reference state. The generalized velocities are the time derivatives of the generalized coordinates of the system. The adjective "generalized" distinguishes these parameters from the traditional use of the term "coordinate" to refer to Cartesian coordinates.

D'Alembert's principle, also known as the Lagrange–d'Alembert principle, is a statement of the fundamental classical laws of motion. It is named after its discoverer, the French physicist and mathematician Jean le Rond d'Alembert, and Italian-French mathematician Joseph Louis Lagrange. D'Alembert's principle generalizes the principle of virtual work from static to dynamical systems by introducing forces of inertia which, when added to the applied forces in a system, result in dynamic equilibrium.

A nonholonomic system in physics and mathematics is a physical system whose state depends on the path taken in order to achieve it. Such a system is described by a set of parameters subject to differential constraints and non-linear constraints, such that when the system evolves along a path in its parameter space but finally returns to the original set of parameter values at the start of the path, the system itself may not have returned to its original state. Nonholonomic mechanics is autonomous division of Newtonian mechanics.

In physics, the Hamilton–Jacobi equation, named after William Rowan Hamilton and Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, is an alternative formulation of classical mechanics, equivalent to other formulations such as Newton's laws of motion, Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics.

In mechanics, virtual work arises in the application of the principle of least action to the study of forces and movement of a mechanical system. The work of a force acting on a particle as it moves along a displacement is different for different displacements. Among all the possible displacements that a particle may follow, called virtual displacements, one will minimize the action. This displacement is therefore the displacement followed by the particle according to the principle of least action.

The work of a force on a particle along a virtual displacement is known as the virtual work.

In rotordynamics, the rigid rotor is a mechanical model of rotating systems. An arbitrary rigid rotor is a 3-dimensional rigid object, such as a top. To orient such an object in space requires three angles, known as Euler angles. A special rigid rotor is the linear rotor requiring only two angles to describe, for example of a diatomic molecule. More general molecules are 3-dimensional, such as water, ammonia, or methane.

In classical mechanics, Routh's procedure or Routhian mechanics is a hybrid formulation of Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics developed by Edward John Routh. Correspondingly, the Routhian is the function which replaces both the Lagrangian and Hamiltonian functions. Although Routhian mechanics is equivalent to Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics, and introduces no new physics, it offers an alternative way to solve mechanical problems.

A pendulum is a body suspended from a fixed support such that it freely swings back and forth under the influence of gravity. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back towards the equilibrium position. When released, the restoring force acting on the pendulum's mass causes it to oscillate about the equilibrium position, swinging it back and forth. The mathematics of pendulums are in general quite complicated. Simplifying assumptions can be made, which in the case of a simple pendulum allow the equations of motion to be solved analytically for small-angle oscillations.

In classical mechanics, holonomic constraints are relations between the position variables that can be expressed in the following form:

In classical mechanics, Appell's equation of motion is an alternative general formulation of classical mechanics described by Josiah Willard Gibbs in 1879 and Paul Émile Appell in 1900.

In fluid dynamics, the Oseen equations describe the flow of a viscous and incompressible fluid at small Reynolds numbers, as formulated by Carl Wilhelm Oseen in 1910. Oseen flow is an improved description of these flows, as compared to Stokes flow, with the (partial) inclusion of convective acceleration.

In classical mechanics, the Udwadia–Kalaba formulation is a method for deriving the equations of motion of a constrained mechanical system. The method was first described by Anatolii Fedorovich Vereshchagin for the particular case of robotic arms, and later generalized to all mechanical systems by Firdaus E. Udwadia and Robert E. Kalaba in 1992. The approach is based on Gauss's principle of least constraint. The Udwadia–Kalaba method applies to both holonomic constraints and nonholonomic constraints, as long as they are linear with respect to the accelerations. The method generalizes to constraint forces that do not obey D'Alembert's principle.

In physics, Lagrangian mechanics is a formulation of classical mechanics founded on the stationary-action principle. It was introduced by the Italian-French mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange in his presentation to the Turin Academy of Science in 1760 culminating in his 1788 grand opus, Mécanique analytique.