The Brigham Young University Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies, situated on Mount of Olives in East Jerusalem, is a satellite campus of Brigham Young University (BYU), the largest religious university in the United States. Owned by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the center provides a curriculum that focuses on Old and New Testament, ancient and modern Near Eastern studies, and language. Classroom study is built around field trips that cover the Holy Land, and the program is open to qualifying full-time undergraduate students at either BYU, BYU-Idaho, or BYU-Hawaii.

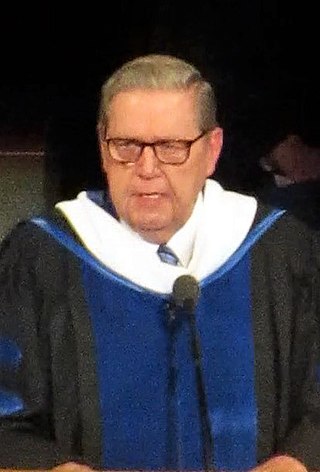

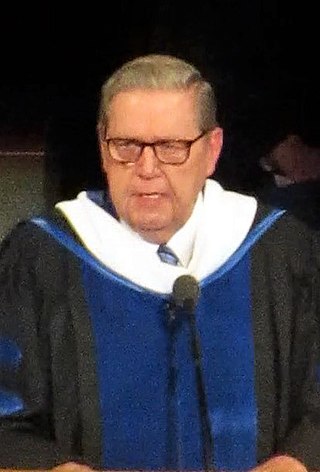

Jeffrey Roy Holland is an American educator and religious leader. He served as the ninth president of Brigham Young University (BYU) and is the acting president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. As a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, Holland is accepted by the church as a prophet, seer, and revelator. Currently, he is the third most senior apostle in the church.

Richard Roswell Lyman was an American engineer and religious leader who was an apostle in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from 1918 to 1943.

The Universe is the official student newspaper for Brigham Young University (BYU) and was started in 1956.

Samuel Woolley Taylor was an American novelist, scriptwriter, and historian.

Ernest Leroy Wilkinson was an American academic administrator, lawyer, and prominent figure in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He was president of Brigham Young University (BYU) from 1951 to 1971, simultaneously overseeing the entire LDS Church Educational System (CES). He is credited with the expansion of BYU. Under his presidency, the student body increased six times to over 25,000 students due to the university's physical growth and his aggressive recruiting policies; the number of colleges at the university increased from five to thirteen, and the number of faculty members increased four-fold. Wilkinson focused on recruiting more faculty and convincing current faculty to receive education outside the university. As a result, the number of teachers with doctorate degrees increased from 50 to 500. Associate and doctoral programs were created for BYU.

The history of Brigham Young University (BYU) begins in 1875, when the school was called Brigham Young Academy (BYA). The school did not reach university status until 1903, in a decision made by the school's board of trustees at the request of BYU president Benjamin Cluff. It became accredited during the tenure of Franklin S. Harris, under whom it gained national recognition as a university. A period of expansion after World War II caused the student body to grow many times in size, making BYU the largest private university of the time. The school's history is closely connected with its sponsor, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The Church Educational System (CES) Honor Code is a set of standards by which students and faculty attending a school owned and operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are required to live. The most widely known university that is part of the Church Educational System (CES) that has adopted the honor code is Brigham Young University (BYU), located in Provo, Utah. The standards are largely derived from codes of conduct of the LDS Church, and were not put into written form until the 1940s. Since then, they have undergone several changes. The CES Honor Code also applies for students attending BYU's sister schools Brigham Young University–Idaho, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, and LDS Business College.

Student life at Brigham Young University is heavily influenced by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The school is privately owned by the church and aims to create an atmosphere in which secular and religious principles are taught in the same classroom.

Brigham Young University Press was the university press of Brigham Young University (BYU).

William Henry Chamberlin Jr. was an American Mormon philosopher, theologian, and educator. His teachings and writings worked to reconcile Mormonism with the theory of evolution. He taught philosophy and ancient languages as well as science and math at several Latter-day Saints (LDS) institutions including Brigham Young University in the early 20th century. He was one of four educators at Brigham Young University whose teaching of evolution and attempts to reconcile it with Mormon thought, although strongly popular with students, generated controversy among university officials and the LDS community. Chamberlin has been called "Mormonism's first professionally trained philosopher and theologian."

The 1911 modernism controversy at Brigham Young University was an episode involving four professors at Brigham Young University (BYU), who between 1908 and 1911 widely taught evolution and higher criticism of the Bible, arguing that modern scientific thought was compatible with Christian and Mormon theology. The professors were popular among students and the community but their teachings concerned administrators, and drew complaints from stake presidents, eventually resulting in the resignation of all four faculty members, an event that "leveled a serious blow to the academic reputation of Brigham Young University—one from which the Mormon school did not fully recover until successive presidential administrations."

USGA is an organization for LGBTQ Brigham Young University students and their allies. It began meeting on BYU campus in 2010 to discuss issues relating to homosexuality and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. However, by December 2012, USGA began meeting off campus at the Provo City Library and is still banned from meeting on campus as of 2018. BYU campus currently offers no official LGBT-specific resources as of 2016. The group maintains political neutrality and upholds BYU's Honor Code. It also asks all participants to be respectful of BYU and the LDS Church. The group received national attention when it released its 2012 "It Gets Better" video. The group also released a suicide prevention message in 2013. A sister organization USGA Rexburg serves the LGBT Brigham Young University–Idaho student community in Rexburg, Idaho.

Students identifying as LGBTQIA+ have a long, documented history at Brigham Young University (BYU), and have experienced a range of treatment by other students and school administrators over the decades. Large surveys of over 7,000 BYU students in 2020 and 2017 found that over 13% had marked their sexual orientation as something other than "strictly heterosexual", while the other survey showed that .2% had reported their gender identity as transgender or something other than cisgender male or female. BYU is the largest religious university in North America and is the flagship institution of the educational system of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints —Mormonism's largest denomination.

This is a timeline of LGBT Mormon history in the 1960s, part of a series of timelines consisting of events, publications, and speeches about LGBTQ+ individuals, topics around sexual orientation and gender minorities, and the community of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Although the historical record is often scarce, evidence points to queer individuals having existed in the Mormon community since its beginnings. However, top LDS leaders only started regularly addressing queer topics in public in the late 1950s. Since 1970, the LDS Church has had at least one official publication or speech from a high-ranking leader referencing LGBT topics every year, and a greater number of LGBT Mormon and former Mormon individuals have received media coverage.

This is a timeline of LGBT Mormon history in the 1970s, part of a series of timelines consisting of events, publications, and speeches about LGBTQ+ individuals, topics around sexual orientation and gender minorities, and the community of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Although the historical record is often scarce, evidence points to queer individuals having existed in the Mormon community since its beginnings. However, top LDS leaders only started regularly addressing queer topics in public in the late 1950s. Since 1970, the LDS Church has had at least one official publication or speech from a high-ranking leader referencing LGBT topics every year, and a greater number of LGBT Mormon and former Mormon individuals have received media coverage.

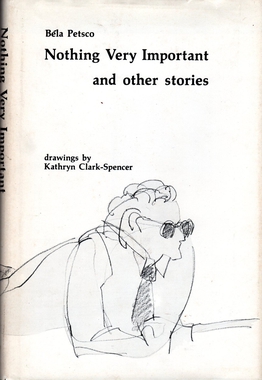

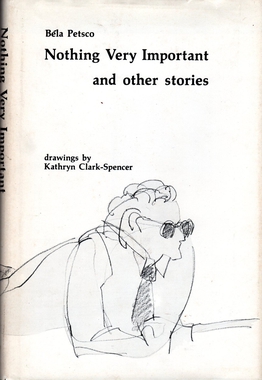

Nothing Very Important and Other Stories is a collection of interconnected short stories written by Béla Petsco and self-published in 1979 with illustrations by his friend Kathryn Clark-Spencer. The stories are about missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints working in Southern California. Signature Books reprinted the book in 1984 under their Orion imprint. Petsco wrote the stories for his master's thesis at Brigham Young University (BYU). The book won the 1979 Association for Mormon Letters award for short fiction. The stories were adapted for theater and performed in 1983, but without BYU's endorsement.

Béla Petsco was an American writer who was the author of Nothing Very Important and Other Stories, a collection of connected stories about missionary work in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He was born to Hungarian immigrants and grew up in Queens in New York City. He converted to the LDS Church after watching the film Brigham Young. He served an LDS mission in the California South mission.

Brent Lee Metcalfe is an independent researcher and writer of the Latter Day Saint Movement.

Below is a timeline of major events, media, and people at the intersection of LGBT topics and Brigham Young University (BYU). BYU is the largest university of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Before 1959 there was little explicit mention of homosexuality by BYU administration.