Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Venezuela face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Venezuela, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples. Also, same-sex marriage and de facto unions are constitutionally banned since 1999.

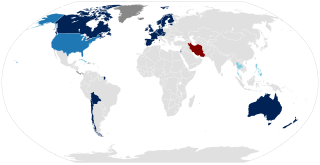

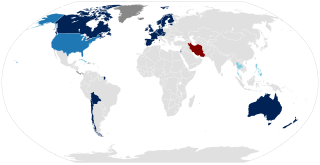

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) personnel are able to serve in the armed forces of some countries around the world: the vast majority of industrialized, Western countries including some South American countries, such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile in addition to other countries, such as the United States, Canada, Japan, Australia, Mexico, France, Finland, Denmark and Israel. The rights concerning intersex people are more vague.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in South Korea face prejudice, discrimination, and other barriers to social inclusion not experienced by their non-LGBT counterparts. Same-sex intercourse is legal for civilians in South Korea, but in the military, same-sex intercourse among soldiers is a crime, and all able-bodied men must complete about two years of military service under the conscript system. South Korean national law does not recognize same-sex marriage or civil unions, nor does it protect against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Same-sex couples cannot jointly adopt, and a 2021 Human Rights Watch investigation found that LGBTQ students face "bullying and harassment, a lack of confidential mental health support, exclusion from school curricula, and gender identity discrimination" in South Korean schools.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Kazakhstan face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female kinds of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Kazakhstan, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Botswana face legal issues not experienced by non-LGBTQ citizens. Both female and male same-sex sexual acts have been legal in Botswana since 11 June 2019 after a unanimous ruling by the High Court of Botswana. Despite an appeal by the government, the ruling was upheld by the Botswana Court of Appeal on 29 November 2021.

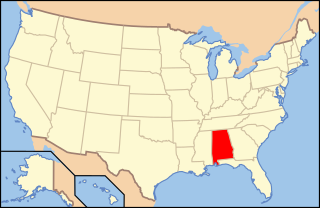

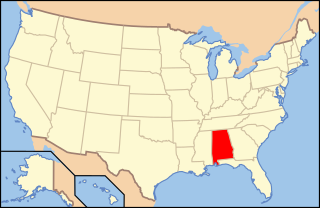

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals in the U.S. state of Alabama have federal protections, but still face legal challenges and discrimination on the state level that is not experienced by non-LGBT residents. LGBTQ rights in Alabama—a Republican Party stronghold located in both the Deep South and greater Bible Belt—are severely limited in comparison to other states. As one of the most socially conservative states in the U.S., Alabama is one of the only two states along with neighboring Mississippi where opposition to same-sex marriage outnumbers support.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of North Carolina may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents, or LGBT residents of other states with more liberal laws.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Rhode Island have the same legal rights as non-LGBTQ people. Rhode Island established two types of major relationship recognition for same-sex couples, starting with civil unions on July 1, 2011, and then on August 1, 2013 with same-sex marriage. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity is outlawed within the state namely in the areas of employment, housing, healthcare and public accommodations. In addition, conversion therapy on minors has been banned since 2017.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Arkansas face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Arkansas. Same-sex marriage became briefly legal through a court ruling on May 9, 2014, subject to court stays and appeals. In June 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that laws banning same-sex marriage are unconstitutional, legalizing same-sex marriage in the United States nationwide including in Arkansas. Nonetheless, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity was not banned in Arkansas until the Supreme Court banned it nationwide in Bostock v. Clayton County in 2020.

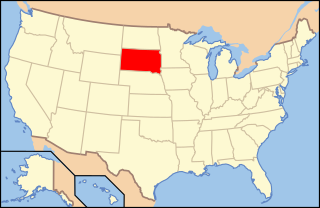

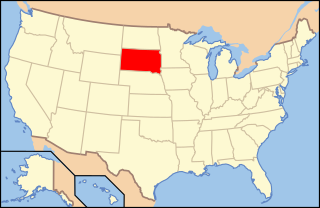

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of South Dakota may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in South Dakota, and same-sex marriages have been recognized since June 2015 as a result of Obergefell v. Hodges. State statutes do not address discrimination on account of sexual orientation or gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal under federal law.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Idaho face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Idaho, and same-sex marriage has been legal in the state since October 2014. State statutes do not address discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal under federal law. A number of cities and counties provide further protections, namely in housing and public accommodations. A 2019 Public Religion Research Institute opinion poll showed that 71% of Idahoans supported anti-discrimination legislation protecting LGBTQ people, and a 2016 survey by the same pollster found majority support for same-sex marriage.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in the U.S. state of Alaska have evolved significantly over the years. Since 1980, same-sex sexual conduct has been allowed, and same-sex couples can marry since October 2014. The state offers few legal protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, leaving LGBTQ people vulnerable to discrimination in housing and public accommodations; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal under federal law. In addition, four Alaskan cities, Anchorage, Juneau, Sitka and Ketchikan, representing about 46% of the state population, have passed discrimination protections for housing and public accommodations.

Sexual orientation and gender identity in the Australian military are not considered disqualifying matters in the 21st century, with the Australian Defence Force (ADF) allowing LGBT people to serve openly and access the same entitlements as other personnel. The ban on gay and lesbian personnel was lifted by the Keating government in 1992, with a 2000 study finding no discernible negative impacts on troop morale. In 2009, the First Rudd government introduced equal entitlements to military retirement pensions and superannuation for the domestic partners of LGBTI personnel. Since 2010, transgender personnel may serve openly and may undergo gender transition with ADF support while continuing their military service. LGBTI personnel are also supported by the charity DEFGLIS, the Defence Force Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender and Intersex Information Service.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBTQ topics:

Not all armed forces have policies explicitly permitting LGBT personnel. Generally speaking, Western European militaries show a greater tendency toward inclusion of LGBT individuals. As of 2022, more than 30 countries allow transgender military personnel to serve openly, such as Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine and the United States. Cuba and Thailand reportedly allowed transgender service in a limited capacity.

In the past most lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) personnel had major restrictions placed on them in terms of service in the United States military. As of 2010 sexual orientation and gender identity in the United States military varies greatly as the United States Armed Forces have become increasingly openly diverse in the regards of LGBTQ people and acceptance towards them.

The Israeli military consists of the Israel Defense Forces and the Israel Border Police, both of which engage in combat to further the nation's goals. Israel's military is one of the most accommodating in the world for LGBT individuals. The country allows homosexual, bisexual, and any other non-heterosexual men and women to participate openly, without policy-based discrimination. Transgender men and women can serve under their identified gender and receive gender affirming surgery. No official military policy prevents intersex individuals from serving, though they may be rejected based on medical concerns.

The issue of transgender people and military service in South Korea is a complex topic, regarding gender identity and bodily autonomy. Currently, transgender women are excluded from the military of South Korea.

This overview shows the regulations regarding military service of non-heterosexuals around the world.

Transgender is a term describing someone with a gender identity inconsistent with that which was assigned to them at birth. In South Korea, transgender communities exist and obtaining gender affirmation surgery is possible, but there are many barriers for transgender people in the country. The former head of the LGBT Human Rights of Korea once stated that "Of all sexual minorities, transgender is the lowest class. They are often abandoned by their families and most of them drop out of school because of bullying. The inconsistency between their appearance and their citizen identification numbers often makes it hard for them to land decent jobs."