Cantonese opera is one of the major categories in Chinese opera, originating in southern China's Guangdong Province. It is popular in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, Macau and among Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. Like all versions of Chinese opera, it is a traditional Chinese art form, involving music, singing, martial arts, acrobatics, and acting.

Qinqiang is a genre of folk Chinese opera originated in Shaanxi Province of Qing China in 1807 and soon took over other genres to be the representative genre of the province. Historically, there were two separate genres both referring themselves as Qinqiang, the one with a longer history was later renamed as Handiao Erhuang (汉调二簧), while the newer genre is the topic of this article.

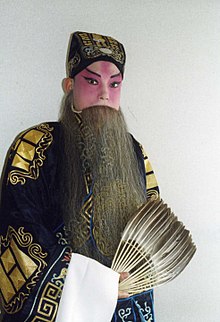

Peking opera, or Beijing opera, is the most dominant form of Chinese opera, which combines instrumental music, vocal performance, mime, martial arts, dance and acrobatics. It arose in Beijing in the mid-Qing dynasty (1644–1912) and became fully developed and recognized by the mid-19th century. The form was extremely popular in the Qing court and has come to be regarded as one of the cultural treasures of China. Major performance troupes are based in Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai. The art form is also preserved in Taiwan, where it is also known as Guójù. It has also spread to other regions such as the United States and Japan.

Kunqu, also known as Kunju (崑劇), K'un-ch'ü, Kun opera or Kunqu Opera, is one of the oldest extant forms of Chinese opera. It evolved from a music style local to Kunshan, part of the Wu cultural area, and later came to dominate Chinese theater from the 16th to the 18th centuries. It has been listed as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. Wei Liangfu refined the musical style of kunqu, and it gained widespread popularity when Liang Chenyu used the style in his drama Huansha ji. In 2006, it was listed on the first national intangible cultural heritage list. In 2008, it was included in the List of Representative Works of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. In December 2018, the General Office of the Ministry of Education announced that Peking University is the base for inheriting excellent traditional Chinese culture in Kunqu.

Taiwanese opera commonly known as Ke-Tse opera or Hokkien opera, is a form of traditional drama originating in Taiwan. Taiwanese opera uses a stylised combination of both the literary and colloquial registers of Taiwanese Hokkien. Its earliest form adopted elements of folk songs from Zhangzhou, Fujian, China. The plots are traditionally drawn from folk tales of the southern Fujian region and Chinese historical legends stories, though in recent years stories are increasingly set in Taiwan itself. Taiwanese opera was later exported to other Hokkien-speaking areas, such as Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Fujian, China.

The wudan is a female role type in Chinese opera and a subtype of the dan. Wudan characters are warrior maidens in combat, and wudan actors must be trained in martial arts with theatrical versions of traditional weapons, as well as in acrobatics and gymnastics.

Huangmei Opera or Huangmei tone is a form of Chinese opera originating from Anqing, Anhui province, as a form of rural folk song and dance. It is also referred to as Anhui Opera. It has been in existence for the last 200 years and possibly longer. Huangmei opera is one of the most famous and mainstream opera in China, and is a class of the typical Anhui opera. The original Huangmei opera was sung by women in Anqing areas when they were picking tea, and the opera was called the Picking Tea Song. In the late Qing dynasty, the songs were popular in Anhui Huaining County adjacent regions, combined with the local folk art, Anqing dialect with singing and chants, and gradually developed into a newborn's operas. The music is performed with a pitch that hits high and stays high for the duration of the song. It is unique in the sense that it does not sound like the typical rhythmic Chinese opera. In the 1960s Hong Kong counted the style as much as an opera as it was a music genre. Today it is more of a traditional performance art with efforts of revival in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, and mostly sung in Mandarin. In 2006, Huangmei Opera was selected for the first batch of China's national intangible cultural heritage.

Zhou Xinfang, also known by his stage name Qilin Tong was a Chinese actor and musician who was a Peking opera actor who specialized in its "old male" roles. He is considered one of the greatest grand masters of Peking Opera of the 20th century and the best known and leading member of the Shanghai school of Peking opera. He was the first director of the Shanghai Peking Opera Company.

Daopao, also known as xuezi when used as a Xifu during Chinese opera performances, and deluo when it is blue in colour, is a traditional form of paofu in Hanfu and is also one of the most distinctive form of traditional clothing for the Han Chinese. The daopao was one of the most common traditional form of outer robe worn by men. Daopao literally means "Taoist robe"; however, despite its name, the daopao were and is worn by men, and did not imply that its wearer had some affiliation to taoism. The daopao can be dated back to at least the Ming dynasty but had actually been worn since the Song dynasty. Initially the daopao was a form of casual clothing which was worn by the middle or lower class in the Ming dynasty. In the middle and late Ming, it was one of the most common form of robes worn by men as casual clothing. The daopao was also a popular formal wear by the Ming dynasty scholars in their daily lives. It was also the daily clothing for the literati scholars in the Ming dynasty. In the late Ming, it was also a popular form of clothing among the external officials and eunuchs sometimes wore it. The daopao was also introduced in Korea during the Joseon period, where it became known as dopo and was eventually localized in its current form.

Anhui Opera, also known as Huiju [徽剧], is a traditional Chinese opera form that originated in Anhui Province during the Ming Dynasty. It is a crucial part of Huizhou culture and significantly contributed to the development of Peking Opera.

Chuanqi is a form of Chinese opera popular in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and early Qing dynasty (1644–1912). It emerged in the mid-Ming dynasty from the older form of nanxi. As it spread throughout the empire, it absorbed regional music styles and topolects and eventually evolved into different local genres, among them kunqu. Of the 2000 plus titles recorded in history, over 600 chuanqi plays are extant and are still performed today, including The Peony Pavilion by Tang Xianzu, The Palace of Eternal Life by Hong Sheng, and The Peach Blossom Fan by Kong Shangren.

Huaihai opera is a form of local traditional Chinese theatre which combines musics, vocal performance, and dance. Some plays contain mime, acrobatics, and Kung fu. It was created in the 19th century and fully developed in the World War II. The form is popular in Shuyang, Suqian, Lianyungang and Yancheng, with the dialect of Shuyang as the standard pronunciation.

Li Shaochun was a Peking opera singer.

Yang Baosen was a Peking opera singer.

The xiaosheng is a male role type in Chinese opera and a subtype of the sheng. Most xiaosheng characters are young Confucian scholars or, less often, young warriors.

Xu Xiaoxiang, born Xu Xin, courtesy name Xinyi and art name Diexian, was a Qing dynasty kunqu and Peking opera artist based in Beijing. He specialized in portraying xiaosheng roles, or younger gentlemen. His best known roles included Zhou Yu in Meeting of Heroes (群英會), Xu Xian in Legend of the White Snake, and Liu Mengmei in The Peony Pavilion.

Mangfu, also known as mangpao, huayi, and python robe, sometimes referred as dragon robe although they are different garments, in English, is a type of paofu, a robe, in hanfu. The mangfu falls under the broad category of mangyi, where the mangfu is considered as being the classic form of mangyi. The mangfu was characterized by the use of a python embroidery called mang although the python embroidery is not a python snake as defined in the English dictionary but a four-clawed Chinese dragon-like creature. The mangfu was derived from the longpao in order to differentiate monarchs and subjects; i.e. only the Emperor is allowed to wear the long, five-clawed dragon, while his subjects wear mang. The mangfu was worn in the Ming and Qing dynasties. They had special status among the Chinese court clothing as they were only second to the longpao. Moreover, their use were restricted, and they were part of a special category of clothing known as cifu, which could only be awarded by the Chinese Emperor in the Ming and Qing dynasties, becoming "a sign of imperial favour". People who were bestowed with mangfu could not exchange it with or gifted it to other people. They were worn by members of the imperial family below of crown prince, by military and civil officials, and by Official wives. As an official clothing, the mangfu were worn by officials during celebration occasions and ceremonial events. They could also be bestowed by the Emperor to people who performed extraordinary services to the empire as rewards, to the members of the Grand Secretariat and to prominent Daoist patriarchs, imperial physicians, tributary countries and local chiefs whose loyalty were considered crucial to secure the borders. The mangfu is also used as a form of xifu, theatrical costume, in Chinese opera, where it is typically found in the form of a round-necked robe, known as yuanlingpao. In Beijing opera, the mangfu used as xifu is known as Mang.

Guzhuang, also called ancient-style dress, refers to a style of Chinese costume attire which are styled or inspired by ancient Chinese clothing. Guzhuang is typically used as stage clothes in Chinese opera and in Chinese television drama, such as in period drama which are normally set in imperial China prior to 1911, and in the Wuxia and Xianxia genre. While the style of guzhuang is based on ancient Chinese clothing, guzhuang show historical inaccuracies.

Lingzi, also called zhiling, refers to a traditional Chinese ornament which uses long pheasant tail feather appendages to decorate some headdress in Xifu, Chinese opera costumes. In Chinese opera, the lingzi not only decorative purpose but are also used express thoughts, feelings, and the drama plot. They are typically used on the helmets of warriors, where a pair of pheasant feathers extensions are the indicators that the character is a warrior figure; the length of the feathers, on the other hand, is an indicator of the warrior's rank. The lingzi are generally about five or six feet long. Most of the time, lingzi are used to represent handsome military commanders.