Kabbalah or Qabalah is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal. The definition of Kabbalah varies according to the tradition and aims of those following it, from its origin in medieval Judaism to its later adaptations in Western esotericism. Jewish Kabbalah is a set of esoteric teachings meant to explain the relationship between the unchanging, eternal God—the mysterious Ein Sof —and the mortal, finite universe. It forms the foundation of mystical religious interpretations within Judaism.

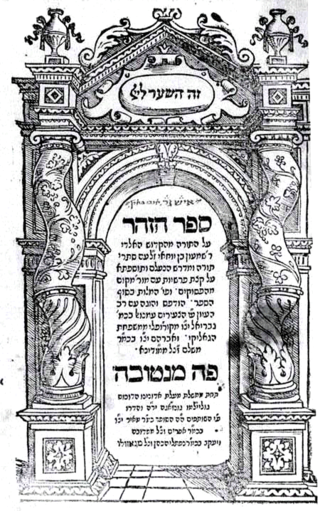

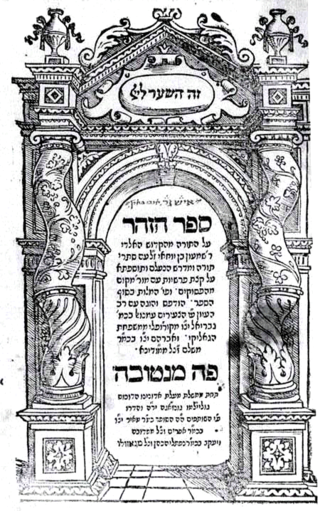

The Zohar is a foundational work of Kabbalistic literature. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah and scriptural interpretations as well as material on mysticism, mythical cosmogony, and mystical psychology. The Zohar contains discussions of the nature of God, the origin and structure of the universe, the nature of souls, redemption, the relationship of Ego to Darkness and "true self" to "The Light of God".

Isaac ben Solomon Luria Ashkenazi, commonly known in Jewish religious circles as Ha'ari, Ha'ari Hakadosh or Arizal, was a leading rabbi and Jewish mystic in the community of Safed in the Galilee region of Ottoman Syria, now Israel. He is considered the father of contemporary Kabbalah, his teachings being referred to as Lurianic Kabbalah.

The Dardaim or Dor Daim, are adherents of the Dor Deah movement in Orthodox Judaism. That movement took its name in 1912 in Yemen under Rabbi Yiḥyah Qafiḥ, and had its own network of synagogues and schools, although, in actuality, the movement existed long before that name had been coined for it. According to ethnographer and historian, Shelomo Dov Goitein, author and historiographer, Hayyim Habshush had been a member of this movement before it had been given the name Dor Deah, writing, “...He and his friends, partly under European influence, but driven mainly by developments among the Yemenite Jews themselves, formed a group who ardently opposed all those forces of mysticism, superstition and fatalism which were then so prevalent in the country and strove for exact knowledge and independent thought, and the application of both to life.” It was only some years later, when Rabbi Yihya Qafih became the headmaster of the new Jewish school in Sana'a built by the Ottoman Turks and where he wanted to introduce a new curriculum in the school whereby boys would also learn arithmetic and the rudiments of the Arabic and Turkish languages that Rabbi Yihya Yitzhak Halevi gave to Rabbi Qafih's movement the name Daradʻah, a word which is an Arabic broken plural made-up of the Hebrew words Dör Deʻoh, and which means "Generation of Knowledge."

Academic study of Jewish mysticism, especially since Gershom Scholem's Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (1941), draws distinctions between different forms of mysticism which were practiced in different eras of Jewish history. Of these, Kabbalah, which emerged in 12th-century southwestern Europe, is the most well known, but it is not the only typological form, nor was it the first form which emerged. Among the previous forms were Merkabah mysticism, and Ashkenazi Hasidim around the time of the emergence of Kabbalah.

Rabbi Yehuda Ashlag (1885–1954) or Yehuda Leib Ha-Levi Ashlag, also known as the Baal Ha-Sulam in reference to his magnum opus, was an orthodox rabbi and kabbalist born in Łuków, Congress Poland, Russian Empire, to a family of scholars connected to the Hasidic courts of Porisov and Belz. Rabbi Ashlag lived in the Holy Land from 1922 until his death in 1954. In addition to his Sulam commentary on the Zohar, his other primary work, Talmud Eser Sefirot is regarded as the central textbook for students of Kabbalah. Ashlag systematically interpreted the wisdom and promoted its wide dissemination. In line with his directives, many contemporary adherents of Ashlag's teachings strive to spread Kabbalah to the masses.

Lag BaOmer, also Lag B'Omer or Lag LaOmer, is a Jewish religious holiday celebrated on the 33rd day of the Counting of the Omer, which occurs on the 18th day of the Hebrew month of Iyar.

Elia del Medigo, also called Elijah Delmedigo or Elias ben Moise del Medigo and sometimes known to his contemporaries as Helias Hebreus Cretensis or in Hebrew Elijah Mi-Qandia. According to Jacob Joshua Ross, "while the non-Jewish students of Delmedigo may have classified him as an “Averroist”, he clearly saw himself as a follower of Maimonides". But, according to other scholars, Delmedigo was clearly a strong follower of Averroes' doctrines, even the more radical ones: unity of intellect, eternity of the world, autonomy of reason from the boundaries of revealed religion.

Isaac ben Samuel of Acre was a Jewish kabbalist who fled to Spain.

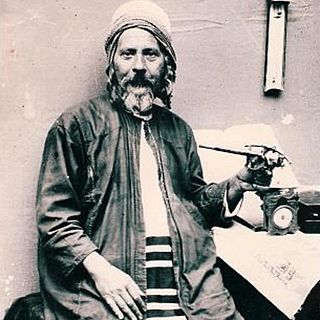

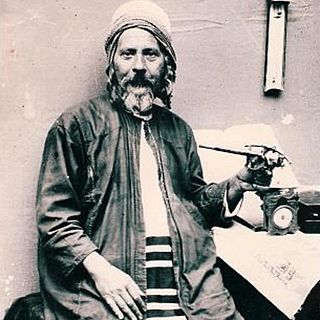

Yiḥyah Qafiḥ (1850–1931), known also by his term of endearment "Ha-Yashish", served as the Chief Rabbi of Sana'a, Yemen in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He was one of the foremost rabbinical scholars in Sana'a during that period, and one who advocated many reforms in Jewish education. Besides being learned in astronomy and in the metaphysical science of rabbinic astrology, as well as in Jewish classical literature which he taught to his young students.

Lurianic Kabbalah is a school of Kabbalah named after Isaac Luria (1534–1572), the Jewish rabbi who developed it. Lurianic Kabbalah gave a seminal new account of Kabbalistic thought that its followers synthesised with, and read into, the earlier Kabbalah of the Zohar that had disseminated in Medieval circles.

The primary texts of Kabbalah were allegedly once part of an ongoing oral tradition. The written texts are obscure and difficult for readers who are unfamiliar with Jewish spirituality which assumes extensive knowledge of the Tanakh, Midrash and halakha.

Sifrei Kodesh, commonly referred to as sefarim, or in its singular form, sefer, are books of Jewish religious literature and are viewed by religious Jews as sacred. These are generally works of Torah literature, i.e. Tanakh and all works that expound on it, including the Mishnah, Midrash, Talmud, and all works of halakha, Musar, Hasidism, Kabbalah, or machshavah. Historically, sifrei kodesh were generally written in Hebrew with some in Judeo-Aramaic or Arabic, although in recent years, thousands of titles in other languages, most notably English, were published. An alternative spelling for 'sefarim' is seforim.

Boaz Huss is a professor of Kabbalah at the Goldstein-Goren Department of Jewish Thought at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He is a leading scholar in contemporary Kabbalah.

Jacob Rakkaḥ, also spelled Raccah, was a Sephardi Hakham in the 19th-century Jewish community of Tripoli, Libya. He was a well-known posek for Sephardi Jews, a rosh yeshiva, and author of approximately 40 sefarim, some of which were published during his lifetime.

Nathan Adadi was a Sephardi Hakham, Torah scholar, and kabbalist in the Jewish community of Tripoli, Libya. He was one of the leaders of the Tripoli Jewish community for some 50 years.

"Bar Yochai" is a kabbalistic piyyut extolling the spiritual attainments of Simeon bar Yochai, the purported author of the preeminent kabbalistic work, the Zohar. Composed in the 16th century by Rabbi Shimon Lavi, a Sephardi Hakham and kabbalist in Tripoli, Libya, it is the most prominent and popular kabbalistic hymn, being sung by Jewish communities around the world. The hymn is sung by Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews alike on Lag BaOmer, the Yom Hillula of bar Yochai, and is also sung during synagogue services and at the Shabbat evening meal by certain groups. Incorporating expressions from the Tanakh, rabbinical commentaries, and the Zohar, the hymn displays its author's own mastery of Torah and kabbalah. According to Isaac Ratzabi, the song's use of "bar Yochai" is the probable reason for "bar Yochai"'s modern ubiquity.

Yehuda Liebes is an Israeli academic and scholar. He is the Gershom Scholem Professor Emeritus of Kabbalah at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Considered a leading scholar of Kabbalah, his research interests also include Jewish myth, Sabbateanism, and the links between Judaism and ancient Greek religion, Christianity, and Islam. He is the recipient of the 1997 Bialik Prize, the 1999 Gershom Scholem Prize for Kabbalah Research, the 2006 EMET Prize for Art, Science and Culture, and the 2017 Israel Prize in Jewish thought.

Shimon Akiva Baer ben Yosef of Vienna was a 17th-century Viennese Talmudist and kabbalistic writer.