Pharmacy is the science and practice of discovering, producing, preparing, dispensing, reviewing and monitoring medications, aiming to ensure the safe, effective, and affordable use of medicines. It is a miscellaneous science as it links health sciences with pharmaceutical sciences and natural sciences. The professional practice is becoming more clinically oriented as most of the drugs are now manufactured by pharmaceutical industries. Based on the setting, pharmacy practice is either classified as community or institutional pharmacy. Providing direct patient care in the community of institutional pharmacies is considered clinical pharmacy.

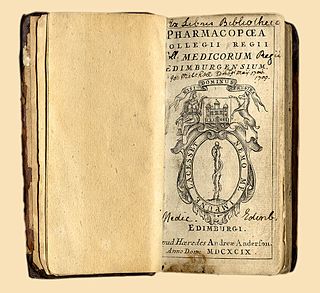

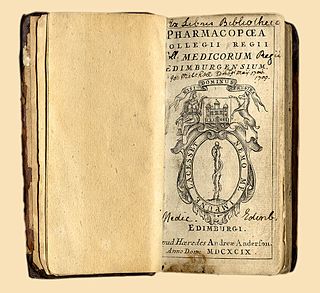

A pharmacopoeia, pharmacopeia, or pharmacopoea, in its modern technical sense, is a book containing directions for the identification of compound medicines, and published by the authority of a government or a medical or pharmaceutical society.

A mortar and pestle is a set of two simple tools used to prepare ingredients or substances by crushing and grinding them into a fine paste or powder in the kitchen, laboratory, and pharmacy. The mortar is characteristically a bowl, typically made of hardwood, metal, ceramic, or hard stone such as granite. The pestle is a blunt, club-shaped object. The substance to be ground, which may be wet or dry, is placed in the mortar where the pestle is pounded, pressed, or rotated into the substance until the desired texture is achieved.

Apothecary is an archaic English term for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses materia medica (medicine) to physicians, surgeons and patients. The modern terms 'pharmacist' and 'chemist' have taken over this role.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society is the body responsible for the leadership and support of the pharmacy profession (pharmacists) within England, Scotland, and Wales. It was created along with the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) in September 2010 when the previous Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain was split so that representative and regulatory functions of the pharmacy profession could be separated. Membership in the society is not a prerequisite for engaging in practice as a pharmacist within the United Kingdom. Its predecessor the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain was founded on 15 April 1841.

In the field of pharmacy, compounding is preparation of custom medications to fit unique needs of patients that cannot be met with mass-produced products. This may be done, for example, to provide medication in a form easier for a given patient to ingest, or to avoid a non-active ingredient a patient is allergic to, or to provide an exact dose that isn't otherwise available. This kind of patient-specific compounding, according to a prescriber's specifications, is referred to as "traditional" compounding. The nature of patient need for such customization can range from absolute necessity to individual optimality to even preference.

A pharmacy is a premises which provides pharmaceutical drugs, among other products. At the pharmacy, a pharmacist oversees the fulfillment of medical prescriptions and is available to counsel patients about prescription and over-the-counter drugs or about health problems and wellness issues. A typical pharmacy would be in the commercial area of a community.

The Apothecary Shop is a building at the Shelburne Museum in Shelburne, Vermont, that exhibits objects salvaged from New England pharmacies that were closing in the early decades of the 20th century. The main room contains dried herbs, spices, drugs, and labeled glass apothecary bottles from the nineteenth century, as well as early patent medicines, medical equipment, cosmetics, and a collection of barbers' razors. The compounding room, with its brick hearth, copper distilleries, and percolators, replicates an illustration found in Edward Parrish's 1871 Treatise on Pharmacy.

A medicinal jar, drug jar, or apothecary jar is a jar used to contain medicines. Ceramic medicinal jars originated in the Islamic world and were brought to Europe where the production of jars flourished from the Middle Ages onward. Potteries were established throughout Europe and many were commissioned to produce jars for pharmacies and monasteries. They are an important category of the Dutch and English porcelain known as Delftware.

Drug packaging is process of packing pharmaceutical preparations for distribution, and the physical packaging in which they are stored. It involves all of the operations from production through drug distribution channels to the end consumer.

The history of pharmacy as a modern and independent science dates back to the first third of the 19th century. Before then, pharmacy evolved from antiquity as part of medicine. The history of pharmacy coincides well with the history of medicine, but it's important that there is a distinction between the two topics. Pharmaceuticals is one of the most-researched fields in the academic industry, but the history surrounding that particular topic is sparse compared to the impact its made world-wide. Before the advent of pharmacists, there existed apothecaries that worked alongside priests and physicians in regard to patient care.

The history of pharmacy in the United States is the story of a melting pot of new pharmaceutical ideas and innovations drawn from advancements that Europeans shared, Native American medicine and newly discovered medicinal plants in the New World. American pharmacy grew from this fertile mixture, and has impacted U.S. history, and the global course of pharmacy.

The Pharmacy Act 1868 was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was the major 19th-century legislation in the United Kingdom limiting the sale of poisons and dangerous drugs to qualified pharmacists and druggists.

Adolph Ferdinand Duflos was a French-born, German pharmacist and chemist.

John Blocki was one of America's pioneer perfumers. His perfumes and cosmetics were widely sold and his unique presentation earned him a U.S. patent for perfumery packaging. He was well-known in the trade for his leadership and commitment to the advancement of the American perfume industry.

Margaret Elizabeth Buchanan was a British pharmacist and pioneer of women in pharmacy.

Rose Coombes Minshull (1845–1905) was one of the first two women members of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (PSGB), admitted in 1879.

Hope Constance Monica Winch was an English pharmacist and academic.

Elsie Higgon was the first Joint Secretary of the (National) Association of Women Pharmacists; researcher for King's College, the British Medical Journal and the British Pharmaceutical Codex; Lecturer in Chemistry at Portsmouth Municipal College; proprietor pharmacist of two businesses in Hampstead, proprietor of the Gordon Hall School of Pharmacy for Women in Gordon Square, and a supporter of the suffrage movement.

William Flockhart, L.R.C.S.E. was a Scottish chemist, a pharmacist who provided chloroform to Doctor James Young Simpson for his anaesthesia experiment at 52 Queen Street, Edinburgh on 4 November 1847. This was the first use of this chemical on humans when Simpson tried it on himself and a few friends, and then used it for pain relief in obstetrics, and surgery. This changed medical practice for over a century, according to the British Medical Journal.