Related Research Articles

Bartholomew de Badlesmere, 1st Baron Badlesmere was an English soldier, diplomat, member of parliament, landowner and nobleman. He was the son and heir of Sir Gunselm de Badlesmere and Joan FitzBernard. He fought in the English army both in France and Scotland during the later years of the reign of Edward I of England and the earlier part of the reign of Edward II of England. He was executed after participating in an unsuccessful rebellion led by Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster.

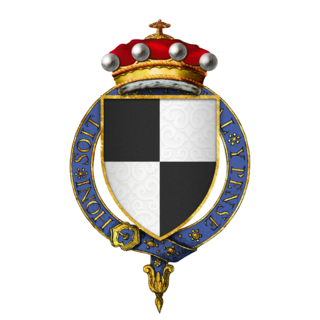

John Devereux, 1st Baron Devereux, KG, was a close companion of Edward, the Black Prince, and an English peer during the reign of King Richard II.

Nicholas de Crioll, of a family seated in Kent, was Constable of Dover Castle and Keeper of the Coast during the early 1260s. His kinsman Bertram de Criol had distinguished himself in these offices during the preceding 20 years and both were near predecessors of the eminent Warden of the Cinque Ports, Stephen de Pencester.

Aldringham is a village in the Blything Hundred of Suffolk, England. The village is located 1 mile south of Leiston and 3 miles northwest of Aldeburgh close to the North Sea coast. The parish includes the coastal village of Thorpeness. The mid-2005 population estimate for Aldringham cum Thorpe parish was 730.

Thomas Hoo, was an English landowner, courtier, soldier, administrator and diplomat who was created a Knight of the Garter in 1446 and Baron Hoo and Hastings in 1448 but left no son to inherit his title.

Maud de Badlesmere, Countess of Oxford was an English noblewoman, and the wife of John de Vere, 7th Earl of Oxford. She, along with her three sisters, was a co-heiress of her only brother Giles de Badlesmere, 2nd Baron Badlesmere, who had no male issue.

Lapley Priory was a priory in Staffordshire, England. Founded at the very end of the Anglo-Saxon period, it was an alien priory, a satellite house of the Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Remi or Saint-Rémy at Reims in Northern France. After great fluctuations in fortune, resulting from changing relations between the rulers of England and France, it was finally dissolved in 1415 and its assets transferred to the collegiate church at Tong, Shropshire.

Campsey Priory was a religious house of Augustinian canonesses at Campsea Ashe, Suffolk, about 1.5 miles (2.5 km) southeast of Wickham Market. It was founded shortly before 1195 on behalf of two of his sisters by Theobald de Valoines, who, with his wife Avice, had previously founded Hickling Priory in Norfolk for male canons in 1185. Both houses were suppressed in 1536.

Sir Nicholas Haute, of Wadden Hall (Wadenhall) in Petham and Waltham, with manors extending into Lower Hardres, Elmsted and Bishopsbourne, in the county of Kent, was an English knight, landowner and politician.

Sir Walter Devereux of Bodenham was a prominent knight in Herefordshire during the reign of Edward III. He was a member of Parliament, sheriff, and Justice of the Peace for Hereford.

John Darras (c.1355–1408) was an English soldier, politician and landowner, who fought in the Hundred Years' War and against the Glyndŵr Rising. A client of the FitzAlan Earls of Arundel, he served them in war and peace, helping consolidate their domination of his native county of Shropshire. He represented Shropshire twice in the House of Commons of England. He died by his own hand.

Sir John Gage was a major English landowner and grandfather of the Tudor courtier Sir John Gage KG.

Eleanor St Clere was the heiress of a substantial number of manors and grandmother of the Tudor courtier Sir John Gage KG.

Sir Philip St Clere was a son of Sir Philip St Clere of Ightham, Kent and Little Preston, Northamptonshire & his wife Joan de Audley. He served as High Sheriff of Surrey and Sussex and was a major landowner whose estates included land in eight English counties.

Margaret de Vere was an English noblewoman, a daughter of John de Vere, 7th Earl of Oxford and his wife Maud de Badlesmere.

Sir John de Pulteney was a major English entrepreneur and property owner, who served four times as Lord Mayor of London.

Sir John Cornwall (c.1366–1414) was an English soldier, politician and landowner, who fought in the Hundred Years' War and against the Glyndŵr Rising. He had considerable prestige, claiming royal descent. As he was part of the Lancastrian affinity, the retainers of John of Gaunt, he received considerable royal favour under Henry IV. He represented Shropshire twice in the House of Commons of England. However, he regularly attracted accusations of violence, intimidation and legal chicanery. Towards the end of his life he fell into disfavour and he died while awaiting trial in connection with a murder.

Nicholas Gainsford, also written Gaynesford or Gaynesforde, of Carshalton, Surrey, of an armigerous gentry family established at Crowhurst, was a Justice of the Peace, several times Member of Parliament and High Sheriff of Surrey and Sussex, Constable and Keeper of Odiham Castle and Park, Hampshire, who served in the royal households from around 1461 until his death in 1498. Rising to high office during the reign of Henry VI, he was an Usher to the Chamber of Edward IV and, by 1476, to his queen Elizabeth Woodville. Closely within the sphere of Woodville patronage, he was a favourer of Edward V, and was a leader in the Kentish rising of 1483 against Richard III. He was attainted in 1483, but was soon afterwards pardoned, and fully regained his position and estate as Esquire to Henry VII and Elizabeth of York after the Battle of Bosworth Field. He established the Carshalton branch of the Gainsford family.

Sir Thomas de Felton was an English landowner, military knight, envoy and administrator. He fought at the Battle of Crécy in 1346, and the Capture of Calais in 1347. He was also at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356. A recurrent figure in the Chronicles of Jean Froissart, he was a signatory to the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360. In 1362 he was appointed Seneschal of Aquitaine. He accompanied Edward the Black Prince on his Spanish campaign. He was taken prisoner by Henry of Trastámara's forces in 1367. In 1372 he was appointed joint-governor of Aquitaine and seneschal of Bordeaux. He caused Guillaume de Pommiers and his secretary to be beheaded for treason in 1377. He was invested a Knight of the Garter in 1381.

Sir Edward de Warren was an illegitimate son of John de Warenne, 7th Earl of Surrey by his mistress Maud de Nerford of Norfolk. He was lord of the manor of Skeyton and also held other lands in Norfolk. His son Sir John de Warren was the first of this surname to succeed to the manors of Stockport and Poynton in Cheshire, and Woodplumpton in Lancashire.

References

- ↑ Sheppard, Walter Lee. "Sir Nicholas de Loveyne and his Two Wives, II". Genealogists' Magazine. 15. London: Society of Genealogists: 288–9.

- ↑ Hasted, Edward (1797). The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 3 (Parishes: Penshurst). Canterbury. pp. 227–257. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ Sheppard, Walter Lee. "Sir Nicholas de Loveyne and his Two Wives, I & II". Genealogists' Magazine. 15. London: Society of Genealogists: 251–255 & 285–292.

- ↑ Lambert, Uvedale (1929). Godstone: a parish history.

- ↑ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, 1st series, Vol. 9, No. 183.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, (1349-54), page 249.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls (1348-50), page 577.

- ↑ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, 1st series, Vol. 12, No. 162.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls (1364-8), pages 394-6.

- ↑ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, 1st series, Vol. 12, No. 321.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 16 (1374-7), page 98.

- ↑ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, 1st series, Vol. 14, No. 172.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 13, 1369-1374, pages 62-3.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 8 (1348-50), page 331.

- ↑ Barber, Richard (2003). The Black Prince. Stroud. p. 168.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 12 (1361-4), page 27.

- ↑ Register of Edward the Black Prince. London: HMSO. 1933. pp. 388, 396 & 478.

- ↑ Beltz, George Frederick (1841). Memorials of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. London. p. 18.

- ↑ Bliss, William Henry (1896). Calendar of entries in the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Petitions to The Pope, Vol. I (1342-1419). London. pp. 373, 381, 382, 386, 417, 421 & 446.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Davis, Virginia (2007). William Wykeham. London. p. 46.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 12 (1364-8), page 15.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 13 (1364-7), page 9.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 14 (1367-70), page 71.

- ↑ "The soldier in later medieval England" . Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 14 (1367-1370), page 434.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward III (1369-1374), Vol. 13, pages 182-185.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 16 (1374-1377), pages 107-9, 111 & 201.

- ↑ 'Woodditton: Manors and other estates', A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 10: Cheveley, Flendish, Staine and Staploe Hundreds (north-eastern Cambridgeshire) (2002), pp. 86-90. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=18798 Date accessed: 3 June 2017.

- ↑ 'Woolwich', The Environs of London: volume 4: Counties of Herts, Essex & Kent (1796), pp. 558-569. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45493 Date accessed: 3 June 2017.

- ↑ Norman, Philip (1901). "Sir John de Pulteney and his Two Residences in London, Cold Harbour and the Manor of the Rose, together with a few remarks on the parish of St Laurence Poultney". Archaeologia. 2. 7. London: Society of Antiquaries of London: 265.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 12 (1364-7), page 178.

- ↑ Calendar Patent Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 12 (1361-4), page 442.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 12 (1364-7), page 188.

- ↑ The Early History of Hedgecourt Manor and Farm

- ↑ Sheppard, Walter Lee. "Sir Nicholas de Loveyne and his Two Wives, II". Genealogists' Magazine. 15. London: Society of Genealogists: 292.

- ↑ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, 1st series, Vol. 16, No. 172.

- ↑ Leland L Duncan. "Medieval & Tudor Wills at Lambeth". Kent Archaeological Society. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ↑ Hermione Hobhouse, ed. (1994). "No. 152 East India Dock Road and Poplar Manor House (demolished)". Survey of London: Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ↑ Blair, John (1980). "Henry Lakenham, Marbler of London, and a Tomb Contract of 1376". Antiquaries Journal. 60. London: Society of Antiquaries of London: 66–74. doi:10.1017/S0003581500035976. S2CID 162981791.

- ↑ The Cistercian abbey of St Mary Graces, East Smithfield, London. London: Museum of London. 2011.