Related Research Articles

Mechthildof Magdeburg, a Beguine, was a Christian medieval mystic, whose book Das fließende Licht der Gottheit is a compendium of visions, prayers, dialogues and mystical accounts. She was the first mystic to write in Low German.

Johannes Tauler OP was a German mystic, a Catholic priest and a theologian. A disciple of Meister Eckhart, he belonged to the Dominican order. Tauler was known as one of the most important Rhineland mystics. He promoted a certain neo-platonist dimension in the Dominican spirituality of his time.

Henry Suso, OP was a German Dominican friar and the most popular vernacular writer of the fourteenth century. Suso is thought to have been born on 21 March 1295. An important author in both Latin and Middle High German, he is also notable for defending Meister Eckhart's legacy after Eckhart was posthumously condemned for heresy in 1329. He died in Ulm on 25 January 1366, and was beatified by the Catholic Church in 1831.

Dietmar von Aist was a Minnesinger from a baronial family in the Duchy of Austria, whose work is representative of the lyric poetry in the Danube region.

Christina Ebner, was a German Dominican nun, writer and mystic.

Eckhart von Hochheim, commonly known as Meister Eckhart, Master Eckhart or Eckehart, claimed original name Johannes Eckhart, was a German Catholic priest, theologian, philosopher and mystic. He was born near Gotha in the Landgraviate of Thuringia in the Holy Roman Empire.

Lüne Monastery is a former Benedictine nunnery in the Lower Saxon town of Lüneburg. Today it is a Protestant Lutheran convent and is managed by the Klosterkammer Hannover. The current abbess is Reinhild Freifrau von der Goltz.

Medingen Abbey or Medingen Convent is a former Cistercian nunnery. Today it is a residence for women of the Protestant Lutheran faith near the Lower Saxon town of Bad Bevensen and is supervised by the Monastic Chamber of Hanover. The current director of the abbey (Äbtissin) is the art historian Dr Kristin Püttmann.

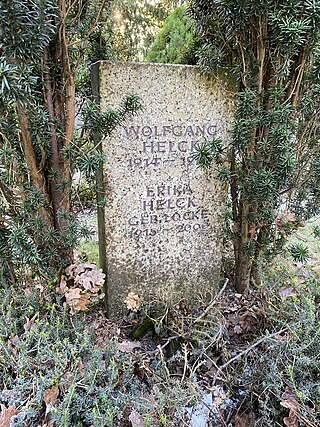

Hans Wolfgang Helck was a German Egyptologist, considered one of the most important Egyptologists of the 20th century. From 1956 until his retirement in 1979 he was a professor at the University of Hamburg. He remained active after his retirement and together with Wolfhart Westendorf published the German Lexikon der Ägyptologie, completed in 1992. He published many books and articles on the history of Egyptian and Near Eastern culture. He was a member of the German Archaeological Institute and a corresponding member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences.

The Liebenau monastery was a Dominican monastery. It was located outside the city gates of Worms in today's Worms-Hochheim district.

Elizabeth of Hungary, was a Hungarian princess and the last member of the House of Árpád. A Dominican nun, Elizabeth spent most of her life in Töss Monastery in today's Switzerland. Despite being the sole surviving member of the first royal house of Hungary, Elizabeth never had any influence on Hungarian politics. She became honored by the local populace as a saint.

Nigel Fenton Palmer FBA was a British Germanist and Professor Emeritus at the University of Oxford.

Friedrich Huch was a German writer.

Weesen Abbey is a monastery of Dominican nuns located in Weesen in the Canton of St. Gallen, Switzerland. The Dominican convent is located at the foot of a terraced hillside in the middle of the town of Weesen on the effluence of the Maag respectively Linth from Walensee. Established in 1256, Weesen is the oldest Dominican friary of nuns in Switzerland. The buildings and the library respectively archives are listed in the Swiss inventory of cultural property of national and regional significance.

Luitgard of Wittichen was a German nun, mystic and founder of a convent.

Annette Marianne Volfing, FBA is a literary scholar and academic. Since 2008, she has been Professor of Medieval German Literature at the University of Oxford.

Helmut Birkhan is an Austrian philologist who is Professor Emeritus of Old High German Language and Literature and the former Managing Director of the Institute for Germanic Studies at the University of Vienna.

Matthias Untermann is a German art historian and medieval archaeologist.

Gerlinde Huber-Rebenich is a German philologist. She specializes in medieval and neo-Latin literature, and the medieval reception of Ovid.

Der Marner was a 13th-century itinerant poet and singer in the Middle High German language, whose work is preserved in the Codex Manesse. He was born in Swabia and obviously enjoyed a good school education. He wrote some of his works in the service of the Hohenstaufen dynasty. According to Meister Rumelant, he went blind in old age and was murdered before 1287, probably during the interregnum.

References

- Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Lindgren, Erika (2006). "Sister Books and Other Convent Chronicles". In Schauss, Margaret (ed.). Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 761–762.

- 1 2 3 Lewis, Gertrud (1996). By Women, for Women, about Women: The Sister-Books of Fourteenth-Century Germany. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies.

- 1 2 3 Lewis, Gertrud (2001). "Sister-Books". In Jeep, John (ed.). Medieval Germany: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 723–724.

- ↑ Siehe Gerard de Fracheto: Vitae fratrum Ordinis Praedicatorum necnon Cronica ordinis ab anno MCCIII usque ad MCCLIV. Hrsg. v. Benedictus Maria Reichert. Löwen 1896 (Monumenta Ordinis Fratrum Praedicatorum Historica I).

- ↑ Hamburger, Jeffrey (1997). Nuns as Artists: The Visual Culture of a Medieval Convent. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Winston-Allen, Anne (2004). Convent chronicles: women writing about women and reform in the late middle ages. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Meyer, Ruth (1995). Das St. Katharinentaler Schwesternbuch. Tübingen: Max Niemayer Verlag. p. 27.

- Sources

- Béatrice W. Acklin-Zimmermann: Gott im Denken berühren. Die theologischen Implikationen der Nonnenviten (= Dokimion 14). Freiburg (Schweiz) 1993.

- Walter Blank: Die Nonnenviten des 14. Jahrhunderts. Eine Studie zur hagiographischen Literatur des Mittelalters unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Visionen und Lichtphänomene. Diss. Freiburg i. Br. 1962

- Patricia Dailey: "Promised Bodies: Time, Language, and Corporeality in Medieval Women's Mystical Texts New York, 2013

- Peter Dronke: Women Writers of the Middle Ages New York 1984

- Hester McNeal Reed Gehring: The Language of Mysticism in South German Dominican Convent Chronicles of the XIVth Century. Phil. Diss. Michigan 1957

- Jeffrey Hamburger: Crown and Veil: Female Monasticism from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries New York, 2008

- Georg Kunze: Studien zu den Nonnenviten des deutschen Mittelalters. Ein Beitrag zur religiösen Literatur im Mittelalter. Diss. (masch.) Hamburg 1953

- Otto Langer: Mystische Erfahrung und spirituelle Theologie. Zu Meister Eckharts Auseinandersetzung mit der Frauenfrömmigkeit seiner Zeit (= Münchener Texte und Untersuchungen zur deutschen Literatur des Mittelalters 91). Artemis, München/Zürich 1987 (Inhaltsverzeichnis).

- Gertrud Jaron Lewis: Bibliographie zur deutschen Frauenmystik des Mittelalters. Mit einem Anhang zu Beatrijs van Nazareth und Hadewijch von Frank Willaert und Marie-Jose Govers (= Bibliographien zur deutschen Literatur des Mittelalters, Heft 10). E. Schmidt, Berlin 1989.

- Gertrud Lewis: By Women, for Women, about Women: The Sister-Books of Fourteenth-Century Germany Toronto 1996

- Ruth Meyer: Das St. Katharinentaler Schwesternbuch. Untersuchung, Edition, Kommentar (= Münchener Texte zur deutschen Literatur des Mittelalters, Band 104). Niemeyer, Tübingen 1995, ISBN 3-484-89104-1, zugleich Dissertation Universität München, 1994 (Edition der Handschrift Kantonsbibliothek Thurgau, Y 74).

- Heinrich Seuse: Zwei Briefe. * Elsbeth Stagel: Sophia von Klingnau. Aus dem Buch vom Leben der Schwestern zu Töss. * Arnold der Rote: Von der Geburt des Herrn. Predigtfragment. (14. Jh.) online über ihn. * Barthlome Fridöwer: Predigt über die Zehn Staffeln der göttlichen Liebe. * Bruder Klaus: Drei Visionen. * Unbekannt: Von einer Heidin. Aus einer Zürcher Handschrift vom Jahr 1393. Sammlung Klosterberg, Schweizerische Reihe. Verlag Benno Schwabe, Basel 1943; wieder Diogenes, Basel 1986, ISBN 3-257-21444-8 (UT: Ausgewählte Proben der schweizerischen Mystik).

- Ursula Peters: Religiöse Erfahrung als literarisches Faktum. Zur Vorgeschichte und Genese frauenmystischer Texte des 13. und 14. Jahrhunderts (= Hermaea NF 56). Niemeyer, Tübingen 1988.

- Siegfried Ringler: Viten- und Offenbarungsliteratur in Frauenklöstern des Mittelalters. Quellen und Studien (= Münchener Texte und Untersuchungen zur deutschen Literatur des Mittelalters 72). Artemis, München 1980, S. 7–15; 257–259; 358f. u. ö. (s. Register: Nonnenviten) Rezension online

- Wolfram Schneider-Lastin: Literaturproduktion und Bibliothek in Oetenbach. – In: Bettelorden, Bruderschaften und Beginen in Zürich: Stadtkultur und Seelenheil im Mittelalter, hrsg. von Barbara Helbling u. a. – Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zürich 2002, S. 188–197. – ISBN 3-85823-970-4 (bes. über das Oetenbacher Schwesternbuch)