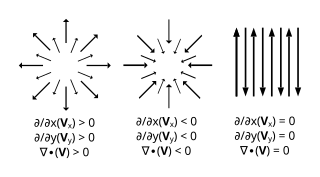

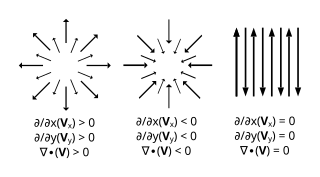

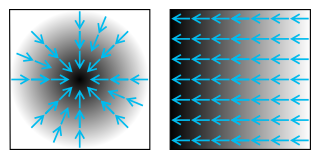

In vector calculus, divergence is a vector operator that operates on a vector field, producing a scalar field giving the quantity of the vector field's source at each point. More technically, the divergence represents the volume density of the outward flux of a vector field from an infinitesimal volume around a given point.

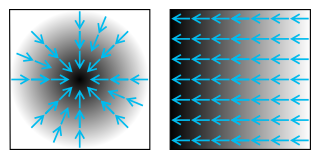

In vector calculus, the gradient of a scalar-valued differentiable function of several variables is the vector field whose value at a point gives the direction and the rate of fastest increase. The gradient transforms like a vector under change of basis of the space of variables of . If the gradient of a function is non-zero at a point , the direction of the gradient is the direction in which the function increases most quickly from , and the magnitude of the gradient is the rate of increase in that direction, the greatest absolute directional derivative. Further, a point where the gradient is the zero vector is known as a stationary point. The gradient thus plays a fundamental role in optimization theory, where it is used to minimize a function by gradient descent. In coordinate-free terms, the gradient of a function may be defined by:

In mathematics and physics, Laplace's equation is a second-order partial differential equation named after Pierre-Simon Laplace, who first studied its properties. This is often written as or where is the Laplace operator, is the divergence operator, is the gradient operator, and is a twice-differentiable real-valued function. The Laplace operator therefore maps a scalar function to another scalar function.

The Navier–Stokes equations are partial differential equations which describe the motion of viscous fluid substances. They were named after French engineer and physicist Claude-Louis Navier and the Irish physicist and mathematician George Gabriel Stokes. They were developed over several decades of progressively building the theories, from 1822 (Navier) to 1842–1850 (Stokes).

In vector calculus, the divergence theorem, also known as Gauss's theorem or Ostrogradsky's theorem, is a theorem relating the flux of a vector field through a closed surface to the divergence of the field in the volume enclosed.

In mathematics, the Laplace operator or Laplacian is a differential operator given by the divergence of the gradient of a scalar function on Euclidean space. It is usually denoted by the symbols , (where is the nabla operator), or . In a Cartesian coordinate system, the Laplacian is given by the sum of second partial derivatives of the function with respect to each independent variable. In other coordinate systems, such as cylindrical and spherical coordinates, the Laplacian also has a useful form. Informally, the Laplacian Δf (p) of a function f at a point p measures by how much the average value of f over small spheres or balls centered at p deviates from f (p).

In mathematics, the covariant derivative is a way of specifying a derivative along tangent vectors of a manifold. Alternatively, the covariant derivative is a way of introducing and working with a connection on a manifold by means of a differential operator, to be contrasted with the approach given by a principal connection on the frame bundle – see affine connection. In the special case of a manifold isometrically embedded into a higher-dimensional Euclidean space, the covariant derivative can be viewed as the orthogonal projection of the Euclidean directional derivative onto the manifold's tangent space. In this case the Euclidean derivative is broken into two parts, the extrinsic normal component and the intrinsic covariant derivative component.

This is a list of some vector calculus formulae for working with common curvilinear coordinate systems.

In mathematics, a Killing vector field, named after Wilhelm Killing, is a vector field on a Riemannian manifold that preserves the metric. Killing fields are the infinitesimal generators of isometries; that is, flows generated by Killing fields are continuous isometries of the manifold. More simply, the flow generates a symmetry, in the sense that moving each point of an object the same distance in the direction of the Killing vector will not distort distances on the object.

In mathematics and physics, the Christoffel symbols are an array of numbers describing a metric connection. The metric connection is a specialization of the affine connection to surfaces or other manifolds endowed with a metric, allowing distances to be measured on that surface. In differential geometry, an affine connection can be defined without reference to a metric, and many additional concepts follow: parallel transport, covariant derivatives, geodesics, etc. also do not require the concept of a metric. However, when a metric is available, these concepts can be directly tied to the "shape" of the manifold itself; that shape is determined by how the tangent space is attached to the cotangent space by the metric tensor. Abstractly, one would say that the manifold has an associated (orthonormal) frame bundle, with each "frame" being a possible choice of a coordinate frame. An invariant metric implies that the structure group of the frame bundle is the orthogonal group O(p, q). As a result, such a manifold is necessarily a (pseudo-)Riemannian manifold. The Christoffel symbols provide a concrete representation of the connection of (pseudo-)Riemannian geometry in terms of coordinates on the manifold. Additional concepts, such as parallel transport, geodesics, etc. can then be expressed in terms of Christoffel symbols.

In differential geometry, the four-gradient is the four-vector analogue of the gradient from vector calculus.

The electromagnetic wave equation is a second-order partial differential equation that describes the propagation of electromagnetic waves through a medium or in a vacuum. It is a three-dimensional form of the wave equation. The homogeneous form of the equation, written in terms of either the electric field E or the magnetic field B, takes the form:

The following are important identities involving derivatives and integrals in vector calculus.

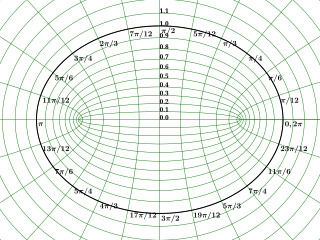

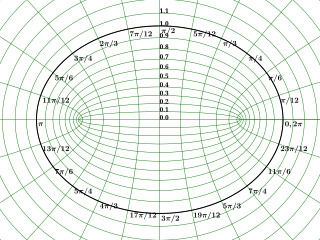

In geometry, the elliptic coordinate system is a two-dimensional orthogonal coordinate system in which the coordinate lines are confocal ellipses and hyperbolae. The two foci and are generally taken to be fixed at and , respectively, on the -axis of the Cartesian coordinate system.

Elliptic cylindrical coordinates are a three-dimensional orthogonal coordinate system that results from projecting the two-dimensional elliptic coordinate system in the perpendicular -direction. Hence, the coordinate surfaces are prisms of confocal ellipses and hyperbolae. The two foci and are generally taken to be fixed at and , respectively, on the -axis of the Cartesian coordinate system.

In physics, the Green's function for the Laplacian in three variables is used to describe the response of a particular type of physical system to a point source. In particular, this Green's function arises in systems that can be described by Poisson's equation, a partial differential equation (PDE) of the form where is the Laplace operator in , is the source term of the system, and is the solution to the equation. Because is a linear differential operator, the solution to a general system of this type can be written as an integral over a distribution of source given by : where the Green's function for Laplacian in three variables describes the response of the system at the point to a point source located at : and the point source is given by , the Dirac delta function.

In mathematics, vector spherical harmonics (VSH) are an extension of the scalar spherical harmonics for use with vector fields. The components of the VSH are complex-valued functions expressed in the spherical coordinate basis vectors.

In fluid dynamics, the Oseen equations describe the flow of a viscous and incompressible fluid at small Reynolds numbers, as formulated by Carl Wilhelm Oseen in 1910. Oseen flow is an improved description of these flows, as compared to Stokes flow, with the (partial) inclusion of convective acceleration.

Curvilinear coordinates can be formulated in tensor calculus, with important applications in physics and engineering, particularly for describing transportation of physical quantities and deformation of matter in fluid mechanics and continuum mechanics.

In theoretical physics, Hamiltonian field theory is the field-theoretic analogue to classical Hamiltonian mechanics. It is a formalism in classical field theory alongside Lagrangian field theory. It also has applications in quantum field theory.