A switcher locomotive, shunter locomotive, or shifter locomotive is a locomotive used for maneuvering railway vehicles over short distances. Switchers do not usually move trains over long distances, instead they typically assemble trains in order for another locomotive to take over. Switchers often operate in a railyard or make short transfer runs. They may serve as the primary motive power on short branch lines or switching and terminal railroads.

A diesel locomotive is a type of railway locomotive in which the power source is a diesel engine. Several types of diesel locomotives have been developed, differing mainly in the means by which mechanical power is conveyed to the driving wheels. The most common are diesel-electric locomotives and diesel-hydraulic.

In railway engineering, the term tractive effort describes the pulling or pushing capability of a locomotive. The published tractive force value for any vehicle may be theoretical—that is, calculated from known or implied mechanical properties—or obtained via testing under controlled conditions. The discussion herein covers the term's usage in mechanical applications in which the final stage of the power transmission system is one or more wheels in frictional contact with a railroad track.

Multiple-unit train control, sometimes abbreviated to multiple-unit or MU, is a method of simultaneously controlling all the traction equipment in a train from a single location—whether it is a multiple unit comprising a number of self-powered passenger cars or a set of locomotives—with only a control signal transmitted to each unit. This contrasts with arrangements where electric motors in different units are connected directly to the power supply switched by a single control mechanism, thus requiring the full traction power to be transmitted through the train.

The EMD GP30 is a 2,250 hp (1,680 kW) four-axle diesel-electric locomotive built by General Motors Electro-Motive Division of La Grange, Illinois between July 1961 and November 1963. A total of 948 units were built for railroads in the United States and Canada, including 40 cabless B units for the Union Pacific Railroad.

The GE U36B is a four-axle 3,600 hp (2.7 MW) B-B diesel-electric locomotive produced by General Electric from 1969 to 1974. It was primarily used by the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad and its successors, although thirteen provided the power for the original Auto Train. The U36B was the last GE high-horsepower universal series locomotive.

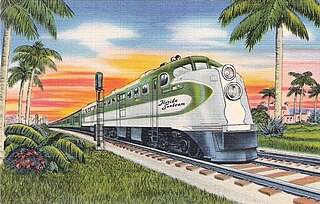

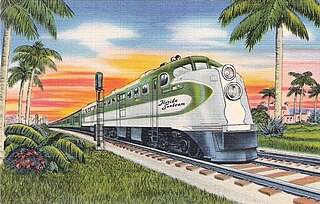

EMD E-units were a line of passenger train streamliner diesel locomotives built by the General Motors Electro-Motive Division (EMD) and its predecessor the Electro-Motive Corporation (EMC). Final assembly for all E-units was in La Grange, Illinois. Production ran from May 1937, to December, 1963. The name E-units refers to the model numbers given to each successive type, which all began with E. The E originally stood for eighteen hundred horsepower, the power of the earliest model, but the letter was kept for later models of higher power.

The EMD FT is a 1,350-horsepower (1,010 kW) diesel-electric locomotive that was produced between March 1939 and November 1945, by General Motors' Electro-Motive Corporation (EMC), later known as GM Electro-Motive Division (EMD). The "F" stood for Fourteen Hundred (1400) horsepower and the "T" for Twin, as it came standard in a two-unit set. The design was developed from the TA model built for the C,RI&P in 1937, and was similar in cylinder count, axle count, length, and layout. All told 555 cab-equipped ”A” units were built, along with 541 cabless booster or ”B” units, for a grand total of 1,096 units. The locomotives were all sold to customers in the United States. It was the first model in EMD's very successful F-unit series of cab unit freight diesels and was the locomotive that convinced many U.S. railroads that the diesel-electric freight locomotive was the future. Many rail historians consider the FT one of the most important locomotive models of all time.

The EMD SD70 is a series of diesel-electric locomotives produced by the US company Electro-Motive Diesel. This locomotive family is an extension and improvisation to the EMD SD60 series. Production commenced in late 1992 and since then over 5,700 units have been produced; most of these are the SD70M, SD70MAC, and SD70ACe models. While the majority of the production was ordered for use in North America, various models of the series have been used worldwide. All locomotives of this series are hood units with C-C trucks, except the SD70ACe-P4 and SD70MACH which have a B1-1B wheel configuration, and the SD70ACe-BB, which has a B+B-B+B wheel arrangement.

The EMD DD35 was a 5,000 horsepower (3,700 kW) diesel-electric locomotive of D-D wheel arrangement built by General Motors Electro-Motive Division for the Union Pacific Railroad and Southern Pacific Railroad.

The EMD SD24 was a 2,400 hp (1,800 kW) six-axle (C-C) diesel-electric locomotive built by General Motors' Electro-Motive Division of La Grange, Illinois between July 1958 and March 1963. A total of 224 units were built for customers in the United States, comprising 179 regular, cab-equipped locomotives and 45 cabless B units. The latter were built solely for the Union Pacific Railroad.

The Consolidation Line was a series of diesel-electric railway locomotive designs produced by Fairbanks-Morse and its Canadian licensee, the Canadian Locomotive Company. Railfans have dubbed these locomotives “C-liners”, however F-M referred to the models collectively as the C-Line. A combined total of 165 units were produced by F-M and the CLC between 1950 and 1955.

In rail transport, a cow-calf is a set of diesel switcher locomotives. The set usually is a pair; some three-unit sets were built, but this was rare. A cow is equipped with a cab; a calf is not. The two are coupled together and equipped with multiple unit train control so that both locomotives can be operated from the single cab.

The ALCO DL-109 was one of six models of A1A-A1A diesel locomotives built to haul passenger trains by the American Locomotive Company (ALCO) between December, 1939 and April, 1945. They were of a cab unit design, and both cab-equipped lead A units DL-103b, DL-105, DL-107, DL-109 and cabless booster B units DL-108, DL-110 models were built. The units were styled by noted industrial designer Otto Kuhler, who incorporated into his characteristic cab the trademark three-piece windshield design. A total of 74 cab units and four cabless booster units were built.

The BLH AS-616 was a 1,600 horsepower (1,200 kW) C-C diesel-electric locomotive built by Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton between 1950 and 1954. Nineteen railroads bought 214 locomotives, and two railroads bought seven cabless B units. The AS-616 was valued for its extremely high tractive effort, far more than any comparable ALCo or EMD product. It was used in much the same manner as its four-axle counterpart, the AS-16, and its six-axle sister, the AS-416, though the six-traction motor design allowed better tractive effort at lower speeds.

The Erie-built was the first streamlined, cab-equipped dual service diesel locomotive built by Fairbanks-Morse, introduced as direct competition to such models as the ALCO PA and FA and EMD FT. F-M lacked the space and staff to design and manufacture large road locomotives in their own plant at Beloit, Wisconsin, and was concerned that waiting to develop the necessary infrastructure would cause them to miss out on the market opportunity for large road locomotives. Engineering and assembly work was subcontracted out to General Electric, which produced the locomotives at its Erie, Pennsylvania, facility, thereby giving rise to the name "Erie-built."

Rhodesia Railways class DE2 are a type of diesel locomotive built for operations on Rhodesia Railways in the 1950s. The first entered service on 22 June 1955.

The Dash 8 Series is a line of diesel-electric freight locomotives built by GE Transportation. It replaced the Dash 7 Series in the mid-1980s, and was superseded by the Dash 9 Series for freight usage and the Genesis Series for passenger usage in the mid-1990s.

The EMD GA18 was an export locomotive built by GM-EMD in 1969. The GA18 was a derivative of the EMD G18 and was designed as an extremely light locomotive with low axle loading which used freight car trucks driven by cardan shafts and two traction motors attached to the underframe. It is the successor model of the EMD GA8. They are powered by an EMD 8-645E prime mover rated at 1100 bhp and 1000 hp for traction. Only seven units were built.

The WDM-2G is a class of diesel electric genset locomotive used in Indian Railways. It is one of the rarest locomotives in India with only two units being produced by Patiala Locomotive Works (PLW). The locomotives were produced with an intention of being fuel efficient and to be used for light to medium duties such as short passenger runs along with occasional shunting. They are one of the only two classes of locomotives in India to feature multiple prime movers, the other example being WDS-6G, which was designed solely for shunting. They have a rated power of 2,400 HP.