Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ "Collaboration de deux sciences voisines: physiologie, sociologie" (Mauss 1936: 373). Furthermore, Freund (1988) discusses the work of F. J. Buytendijk (1974), which "is one example of an effort to redefine mechanistic physiology in such a way as to include subjectivity and social existence as interrelated aspects of our physical being" (Freund 1988: 847), such that there exists a "mutually 'conditioning' relation between sociopsychological and biological factors. Social environments 'construct' bodies, which in turn affect social behavior, and this behavior in turn further modifies bodies" (Freund 1988: 849).

- ↑ "Die physische Seite der Wechselbeziehungen der Menschen kann nichtsdestoweniger Gegenstand einer besonderen Naturwissenschaft sein, welche ich als "physiologische Soziologie" oder besser "Soziophysiologie" zu bezeichnen vorschlage" (Zeliony 1912: 405-406). Zeliony’s 1912 paper — the earliest known which uses the term "sociophysiology" and its derivatives, e.g., Soziophysiologie, soziophysiologische, etc. — was originally delivered as a lecture to the Saint Petersburg Philosophical Society on March 19, 1909 (Zeliony 1912: 405). Although Zeliony (1912: 406) attributes the term "sociophysiology" to Russian philosopher A. I. Wedensky, Paul von Lilienfeld, in 1879, published a book titled Social Physiology, which uses throughout the unified concept, conjoined with a dash, "social-physiology" [social-physiologie] in addition to the modified substantive, separated by a space, "social physiology" [sociale Physiologie]. G. P. Zeliony, a worker in Pavlov's lab, took as the starting point for his "future sociophysiology," the study of the "reflexive interrelations" [reflektorischen Wechselbeziehungen] of humans and other animals (Zeliony 1912: 405; 412–413).

- ↑ "Éthologie sociale; énergétique sociale — physiologie des phénomènes réactionnels dus aux excitations mutuelles des individus de même espèce" (Waxweiler 1906: 62).

- ↑ "Étude socio-psycho-biologique" (Mauss 1936: 386); "phénomènes biologico-sociologiques" (Mauss 1936: 385).

- ↑ "Liens étroits qui unissent les phénomènes sociologiques aux phénomènes biologiques dont ils dérivent immédiatement" (Solvay 1906: 26).

- ↑ "Phénomènes physic- et psycho-énergétiques à la base des groupements sociaux" (Rolvaag 1906: 25). Such phenomena are now known to involve neurotransmitters, hormones, pheromones, the immune system, etc.

- ↑ "Die physiologische Socialpathologie" (Lilienfeld 1879: 280); "Pathologische Soziophysiologie" (Zeliony 1912: 405).

Related Research Articles

In sociology, habitus is the way that people perceive and respond to the social world they inhabit, by way of their personal habits, skills, and disposition of character. People with a common cultural background share a habitus as the way that group culture and personal history shape the mind of a person; consequently, the habitus of a person influences and shapes the social actions of the person.

David Émile Durkheim was a French sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern social science, along with both Karl Marx and Max Weber.

Pierre Maurice Marie Duhem was a French theoretical physicist who worked on thermodynamics, hydrodynamics, and the theory of elasticity. Duhem was also a historian of science, noted for his work on the European Middle Ages, which is regarded as having created the field of the history of medieval science. As a philosopher of science, he is remembered principally for his views on the indeterminacy of experimental criteria.

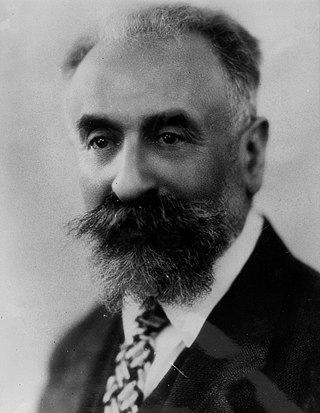

Marcel Mauss was a French sociologist and anthropologist known as the "father of French ethnology". The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and anthropology. Today, he is perhaps better recognised for his influence on the latter discipline, particularly with respect to his analyses of topics such as magic, sacrifice and gift exchange in different cultures around the world. Mauss had a significant influence upon Claude Lévi-Strauss, the founder of structural anthropology. His most famous work is The Gift (1925).

The sociology of law is often described as a sub-discipline of sociology or an interdisciplinary approach within legal studies. Some see sociology of law as belonging "necessarily" to the field of sociology, but others tend to consider it a field of research caught up between the disciplines of law and sociology. Still others regard it as neither a subdiscipline of sociology nor a branch of legal studies but as a field of research on its own right within the broader social science tradition. Accordingly, it may be described without reference to mainstream sociology as "the systematic, theoretically grounded, empirical study of law as a set of social practices or as an aspect or field of social experience". It has been seen as treating law and justice as fundamental institutions of the basic structure of society mediating "between political and economic interests, between culture and the normative order of society, establishing and maintaining interdependence, and constituting themselves as sources of consensus, coercion and social control".

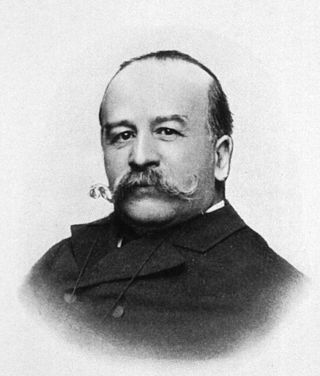

Paul Frommhold Ignatius von Lilienfeld-Toal was a Baltic German statesman and social scientist of imperial Russia. He was governor of the Courland Governorate from 1868 till 1885. During that time, he developed his Thoughts on the Social Science of the Future, first in Russian as Мысли о социальной науке будущего, and then in German as Gedanken über die Socialwissenschaft der Zukunft (1873–1881). Lilienfeld's thoughts, which he later articulated in compressed form in both French and Italian, laid out his organic theory of societies, also known as the social organism theory, organicist sociology, or simply organicism. He later became a senator in the Russian parliament, as well as vice-president (1896), then president (1897), of the Institut International de Sociologie in Paris.

Georgii Pavlovich Zeliony was a Russian physiologist who contributed to the understanding of conditional and unconditional reflexes. He was one of I. P. Pavlov's first students. His studies of decorticated dogs led to knowledge of brain function in man and other animals. In addition, he was the first to articulate the theoretical underpinnings of sociophysiology.

Éric Brian is a historian of science and a sociologist. He studies the uncertainty and regularity of social phenomena, and in particular, how scientists have caught and conceived them as objects of mathematics or social and economic sciences.

Marie Jaisson is a sociologist studying the sociology of medical practices and of biological phenomena, and the history of Sociology. After a Ph.D. in Sociology at EHESS (Paris), she was junior professor at the [University of Tours] and she is full professor at the University Sorbonne Paris-Nord (France).

The Solvay Institute of Sociology [SIS; Institut de Sociologie Solvay] assumed its first "definitive form" on November 16, 1902, when its founder Ernest Solvay, a wealthy Belgian chemist, industrialist, and philanthropist, inaugurated the original edifice of SIS in Parc Léopold. Under the guidance of its first director, Emile Waxweiler, SIS expressed a "conception of a sociology open to all of the disciplines of the human sciences: ethnology, of course, but also economics [...] and psycho-physiology, contact with which was facilitated by the proximity of the Institute of Physiology". While SIS is now part of the Université Libre de Bruxelles and known more simply as that university's Institute of Sociology [Institut de Sociologie], the approach instigated by Solvay and Waxweiler still serves as methodological framework: a synergy between basic and applied research involving interdisciplinary studies firmly anchored in social life.

Alexandre Lacassagne was a French physician and criminologist who was a native of Cahors. He was the founder of the Lacassagne school of criminology, based in Lyon and influential from 1885 to 1914, and the main rival to Lombroso's Italian school.

Emile Waxweiler (1867–1916) was a Belgian engineer and sociologist. He was a member of the Royal Academy of Belgium as well as the International Institute of Statistics.

Michel Maffesoli is a French sociologist.

Gilbert Durand was a French academic known for his work on the imaginary, symbolic anthropology and mythology.

Patricia Barchas (1934-1993) was a scholar committed to the study of the interaction of social behavior and physiological processes. She was a pioneer in the study of brain electrical activity and hormonal function in social processes, such as the development of status hierarchies in small social groups.

Eugène Dupréel was a Belgian philosopher. He has been professor at the Université libre de Bruxelles from 1907 to 1950, teaching logic, metaphysics, greek philosophy, moral philosophy and sociological theory. He developed an ethical theory and a theory of knowledge deeply influenced by sociology, and worked closely with the Institut de Sociologie Solvay. Leader of the "École de Bruxelles", he had a major influence on the argumentation theorist Chaïm Perelman and thus has been instrumental in the renewal of rhetoric.

Alain Testart was a French social anthropologist, emeritus research director at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in Paris and member of the Laboratory for Social Anthropology at the Collège de France. He specialized in primitives societies and comparative anthropology. His research themes included: slavery, marriage arrangements, funeral practices, gift and exchange, typology of societies, the political, the evolution of the societies, and questions of interpretation in prehistoric archaeology.

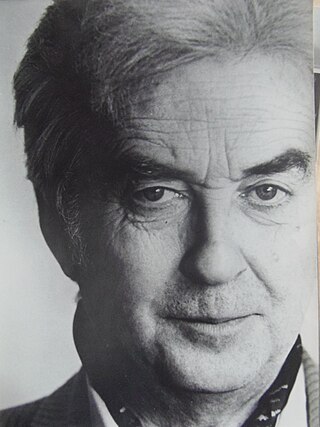

Julien Freund was a French philosopher and sociologist. Freund was called an "unsatisfied liberal-conservative" by Pierre-André Taguieff, for introducing France to the ideas of Max Weber. His work as a sociologist and political theorist is a continuation of Carl Schmitt's. Freund, like many people from Alsace, was fluent in German and French. His works have been translated into nearly 20 languages.

Barbare "Varia" Kipiani was the first Georgian trained as a psychophysiologist and is recognized as a pioneering woman scholar of Georgia. Born into a noble family, Kipiani and her sisters were raised by her father after her parents' divorce. After graduating from St. Nino's School in Tbilisi in 1899, she taught in a school in Khoni for two years. Moving to Belgium, where her father had relocated, she entered the medical faculty of the Free University of Brussels in 1902. Unable to afford her tuition, Kipiani was mentored by Polish academic, Józefa Joteyko, who paid her school fees and allowed her to work in a laboratory. She wrote a paper titled "L'ergographie du sucre", which evaluated the use of sugar in alleviating fatigue. Her study won a silver medal from the Association des chimistes de France et des colonies in 1906. After completing her coursework in the medical faculty in 1907, Kipiani lectured at various universities and continued research with Joteyko on nutrition and fatigue. They jointly were awarded the Vernois Prize of the French Académie Nationale de Médecine in 1908 for their work on vegetarianism.

Nadine Ivanitzky was a Ukrainian sociologist who specialized in research on primitive people. After earning a degree from the University of Geneva, she attended courses at the Sorbonne and earned a doctorate from the Free University of Brussels. Her doctoral advisor was Emile Waxweiler, who hired her as one of the ten permanent researchers at the Solvay Institute of Sociology. She was in charge of cultural anthropological research at the institute and became a specialist in studying pre-industrial cultures.

References

- Adler, H. M. (2002). The sociophysiology of caring in the doctor–patient relationship. Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 17, no. 11, pp. 883–890.

- Barchas, P. R. (1986). A sociophysiological orientation to small groups. In E. J. Lawler, ed., Advances in Group Processes, vol. 3, pp. 209–246. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Di Mascio, A., Boyd, R. W., Greenblatt, M., and H. C. Solomon. (1955). The psychiatric interview (a sociophysiologic study). Diseases of the Nervous System, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 4–9.

- Ellwood, C. A. (1916). Objectivism in sociology. American Journal of Sociology, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 289–305.

- Freund, P. E. S. (1988). Bringing society into the body: Understanding socialized human nature. Theory and Society, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 839–864.

- Gardner Jr., R. J. (1997). Sociophysiology as the basic science of psychiatry. Theoretical Medicine, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 335–356.

- Gardner Jr., R. J., and J. S. Price. (1999). Sociophysiology and depression. In T. E. Joiner and J. C. Coyne, eds., The Interactional Nature of Depression: Advances in Interpersonal Approaches. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Lilienfeld, P. (1879). Die sociale Physiologie. Volume 4 of Gedanken über die Socialwissenschaft der Zukunft. Mitau: E. Behre's Verlag.

- Mauss, M. (1936). Les techniques du corps. Journal de Psychologie, vol. 32, nos. 3–4, 15 mars – 15 avril 1936. Reprinted in M. Mauss, Sociologie et anthropologie, Paris: PUF, 1950, pp. xxx-xxx. doi : 10.1522/cla.mam.tec

- Oxley, D. R. et al. (2008). Political attitudes vary with physiological traits. Science 19 September 2008: Vol. 321. no. 5896, pp. 1667–1670. doi : 10.1126/science.1157627

- Solvay, E. (1906). Note sur des formules d’introduction à l’énergétique physio- et psycho-sociologique. Fascicule 1 des Notes et Mémoires de l’Institut de Sociologie, Instituts Solvay, Parc Léopold, Bruxelles. Bruxelles et Leipzig: Misch et Thron.

- Waxweiler, E. (1906). Esquisse d’une sociologie. Fascicule 2 des Notes et Mémoires de l’Institut de Sociologie, Instituts Solvay, Parc Léopold, Bruxelles. Bruxelles et Leipzig: Misch et Thron.

- Zeliony, G. P. (1912). Über die zukünftige Soziophysiologie. Archiv für Rassen- und Gesellschafts-Biologie, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 405–429.