Related Research Articles

The Testament of Adam is a Christian work of Old Testament pseudepigrapha that dates from the 2nd to 5th centuries AD in origin, perhaps composed within the Christian communities of Syria. It purports to relate the final words of Adam to his son Seth; Seth records the Testament and then buries the account in the legendary Cave of Treasures. Adam speaks of prayer and which parts of Creation praise God each hour of the day; he then prophesies both the coming of the Messiah and the Great Flood; and finally, a description of the celestial hierarchy of angels is given.

The story of Dhu al-Qarnayn is mentioned in Surah al-Kahf of the Quran. It has long been recognised in modern scholarship that the story of Dhu al-Qarnayn has strong similarities with the Syriac Legend of Alexander the Great. According to this legend, Alexander travelled to the ends of the world then built a wall in the Caucasus Mountains to keep Gog and Magog out of civilized lands.

The Fountain of Life, or in its earlier form the Fountain of Living Waters, is a Christian iconography symbol associated with baptism and/or eucharist, first appearing in the 5th century in illuminated manuscripts and later in other art forms such as panel paintings.

Syriac literature is literature in the Syriac language. It is a tradition going back to the Late Antiquity. It is strongly associated with Syriac Christianity.

The Alexander Romance is an account of the life and exploits of Alexander the Great. Of uncertain authorship, it has been described as "antiquity's most successful novel". The Romance describes Alexander the Great from his birth, to his succession of the throne of Macedon, his conquests including that of the Persian Empire, and finally his death. Although constructed around a historical core, the romance is mostly fantastical, including many miraculous tales and encounters with mythical creatures such as sirens or centaurs. In this context, the term Romance refers not to the meaning of the word in modern times but in the Old French sense of a novel or roman, a "lengthy prose narrative of a complex and fictional character".

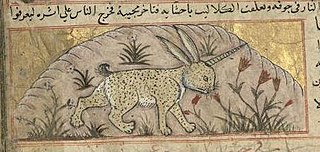

Al-Mi'raj or Almiraj is a mythical creature resembling a one-horned hare or rabbit, mentioned in medieval Arabic literature.

Apocalypse of Pseudo-Ephraem is a pseudoepigraphical text attributed to the church father Ephrem the Syrian. Two distinct documents have survived — one in Syriac and one in Latin. The Syriac document focuses on apocalyptic themes through the lens of Middle Eastern events which took place at the time it was written. Confusion exists around the Pseudo-Ephraem text primarily because of its doubtful authorship and date, differences between the Syriac and Latin versions, the small number of extant manuscripts, and the limited study that has been conducted of the text. Additionally, many extant works have been ascribed to Ephrem despite his authorship of these documents being doubtful. This has created significant difficulty in the area of textual criticism.

Odontotyrannos, also odontotyrannus or dentityrannus ("tooth-tyrant") is a mythical three-horned beast said to have attacked Alexander the Great and his men at their camp in India, according to the apocryphal Letter from Alexander to Aristotle and other medieval romantic retellings of Alexandrian legend.

The vast conquests of the Macedonian king Alexander the Great quickly inspired the formation and diffusion of legendary material about his deity, journeys, and tales. These appeared shortly after his death, and some may have already begun forming during his lifetime. Common themes and symbols among legends about Alexander include the Gates of Alexander, the Horns of Alexander, and the Gordian Knot.

Christina, born Yazdoi, was a Sasanian Persian noblewoman and Christian venerated after her death as a virgin martyr.

Jean-Baptiste Chabot was a Roman Catholic secular priest and the leading French Syriac scholar in the first half of the twentieth century.

The History of the Captivity in Babylon is a pseudepigraphical text of the Old Testament that supposedly provides omitted details concerning the prophet Jeremiah. It is preserved in Coptic, Arabic, and Garshuni manuscripts. It was most likely originally written in Greek sometime between 70 and 132 CE by a Jewish author and then subsequently reworked into a second, Christian edition in the form of 4 Baruch. It is no. 227 in the Clavis apocryphorum Veteris Testamenti, where it is referred to as Apocryphon Jeremiae de captivitate Babylonis. However, the simple form Apocryphon of Jeremiah, which is sometimes employed, should be avoided as the latter is used to describe fragments among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The Mingana Collection of Middle Eastern manuscripts, comprising over 3,000 documents, is held by the University of Birmingham's Cadbury Research Library.

The Syriac Alexander Legend, is a Syriac legendary account of the exploits of Alexander the Great composed in the sixth or seventh century. For the first time in this text, the motifs of Gates of Alexander, an apocalyptic incursion, and the barbarian tribes of Gog and Magog are fused into a single narrative. The Legend would go on to influence Syriac literature about Alexander, like in the Song of Alexander. It would also exert a strong influence on subsequent apocalyptic literature, like the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius composed in the late seventh century. In Quranic studies, the representation of Alexander in the Legend is also seen as closely related to the Quranic figure named Dhu al-Qarnayn.

The Legend of Hilaria is a Coptic romance, possibly a Christian version of the pagan Tale of Bentresh. It was written between the 6th and 9th centuries AD. During the Middle Ages, it was translated into Syriac, Arabic and Ethiopic. It tells the tale of Hilaria, daughter of the Roman emperor Zeno, who disguised herself as a man to become a monk and later heals her sister of an ailment. The tale was incorporated into the synaxaries of the Oriental Orthodox churches, and Hilaria came to be celebrated as a saint.

The Apocalypse of Pseudo-Ezra is a set of visions of the end times composed in the Syriac language sometime between the 7th and 12th centuries. It is a pseudepigraphon falsely attributed to Ezra. It is a short text of about seven manuscript pages. It recapitulates history in the form of prophecy using obscure animal imagery. Written to console Christians living under Islamic rule, it predicts the end of such rule in the Near East.

The Horns of Alexander represent an artistic tradition that depicted Alexander the Great with two horns on his head, a form of expression that was associated originally as the Horns of Ammon. Alexander's horns came with connotations of political and/or religious legitimacy, including indications of his status as a god, and these representations of Alexander under his successors carried implications of their divine lineage or succession from his reign. Mediums of expression of the horns of Alexander included coinage, sculpture, medallions, textiles, and literary texts, such as in the tradition of the Alexander Romance literature. Rarely was anyone other than Alexander depicted with the two horns as this was considered unique to his imagery.

The Armenian Alexander Romance, known in Armenian as The History of Alexander of Macedon, is an Armenian recension of the Greek Alexander Romance from the fifth-century. It incorporates many of its own elements, materials, and narratives not found in the original Greek version. While the text did not substantially influence Eastern legend, the Armenian romance is considered to be a highly important resource in reconstructing the text of the original Greek romance. The text continued to be copied until the eighteenth century, and the first Armenian and scholar to substantially study the text was Father Raphael Tʿreanc. He published an Armenian edition of it in 1842.

The Syriac Alexander Romance is an anonymous Christian text in the tradition of the Greek Alexander Romance of Pseudo-Callisthenes, potentially translated into Syriac the late sixth or early seventh century. Just like the Res gestae Alexandri Macedonis of Julius Valerius Alexander Polemius, the Armenian Alexander Romance and the Historia de preliis of Leo the Archpriest, the Syriac Romance belongs to the α recension of the Greek Romance, as is represented by the Greek manuscript A. Another text, the Syriac Alexander Legend, appears as an appendix in manuscripts of the Syriac Alexander Romance, but the inclusion of the Legend into manuscripts of the Romance is the work of later redactors and does not reflect an original relationship between the two.

Alexander the Great was the king of the Kingdom of Macedon and the founder of an empire that stretched from Greece to northwestern India. Legends surrounding his life quickly sprung up soon after his own death. His predecessors represented him in their coinage as the son of Zeus Ammon, wearing what would become the Horns of Alexander as originally signified by the Horns of Ammon. Legends of Alexander's exploits coalesced into the third-century Alexander Romance which, in the premodern period, went through over one hundred recensions, translations, and derivations and was translated into almost every European vernacular and every language of the Islamic world. After the Bible, it was the most popular form of European literature. It was also translated into every language from the Islamicized regions of Asia and Africa, from Mali to Malaysia.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Reinink, Gerrit J. (2003). "Alexander the Great in Seventh-Century Syriac 'Apocalyptic' Texts". Byzantinorossica. 2: 150–178.

- ↑ Nöldeke, Theodor (1890). Beiträge zur geschichte des Alexanderromans. University of Michigan. Wien, F. Tempsky. pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Bousset, Wilhelm (1900). "Beiträge zur Geschichte der Eschatologie". Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte (in German). 20 (2).

- 1 2 Tesei 2023, p. 22.

- ↑ E. A. Wallis Budge. The History of Alexander the Great, being the Syriac version of the Pseudo-Callisthenes. pp. 163–200.

- 1 2 Monferrer-Sala, Juan Pedro (2011-01-01), "Chapter Three. Alexander The Great In The Syriac Literary Tradition", A Companion to Alexander Literature in the Middle Ages, Brill, p. 45, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004183452.i-410.24, ISBN 978-90-04-21193-3 , retrieved 2024-03-25

- 1 2 Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2018). The Qur'an and the Bible: text and commentary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 463–465. ISBN 978-0-300-18132-6.

- ↑ Crone, Patricia (2016). Islam, the Ancient Near East and Varieties of Godlessness: Collected Studies in Three Volumes, Volume 3. Brill. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-90-04-31931-8.

Sources

- Tesei, Tommaso (2023). The Syriac Legend of Alexander's Gate. Oxford University Press.