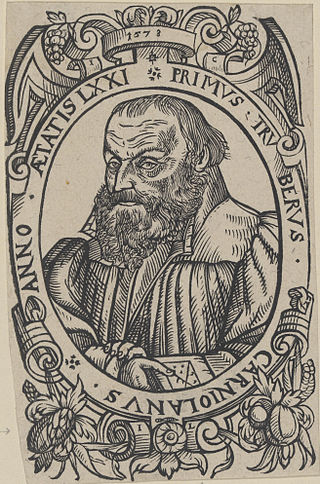

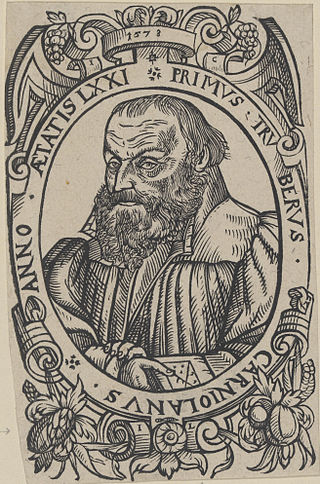

Primož Trubar or Primus Truber was a Slovene Protestant Reformer of the Lutheran tradition, mostly known as the author of the first Slovene language printed book, the founder and the first superintendent of the Protestant Church of the Duchy of Carniola, and for consolidating the Slovenian language. Trubar introduced The Reformation in Slovenia, leading the Austrian Habsburgs to wage the Counter-Reformation, which a small Protestant community survived. Trubar is a key figure of Slovenian history and in many aspects a major historical personality.

Shtokavian or Štokavian is the prestige supradialect of the pluricentric Serbo-Croatian language and the basis of its Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian and Montenegrin standards. It is a part of the South Slavic dialect continuum. Its name comes from the form for the interrogative pronoun for "what" što. This is in contrast to Kajkavian and Chakavian.

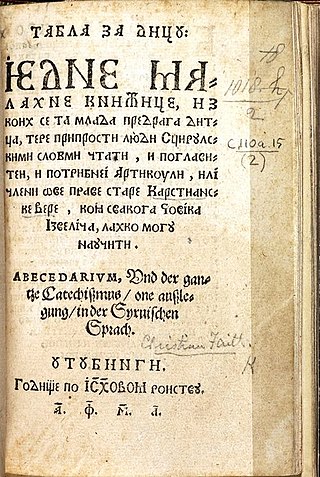

Bosnian Cyrillic, widely known as Bosančica, is a variant of the Cyrillic alphabet that originated in medieval Bosnia. The term was coined at the end of the 19th century by Ćiro Truhelka. It was widely used in modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina and the bordering areas of modern-day Croatia. Its name in Serbo-Croatian is Bosančica and Bosanica the latter of which might be translated as Bosnian script. Serb scholars call it Serbian script, Serbian–Bosnian script, Bosnian–Serb Cyrillic, as part of variant of Serbian Cyrillic and deem the term "bosančica" Austro-Hungarian propaganda. Croat scholars also call it Croatian script, Croatian–Bosnian script, Bosnian–Croat Cyrillic, harvacko pismo, arvatica or Western Cyrillic. For other names of Bosnian Cyrillic, see below.

In a purely dialectological sense, Slovene dialects are the regionally diverse varieties that evolved from old Slovene, a South Slavic language of which the standardized modern version is Standard Slovene. This also includes several dialects in Croatia, most notably the so-called Western Goran dialect, which is actually Kostel dialect. In reality, speakers in Croatia self-identify themselves as speaking Croatian, which is a result of a ten centuries old country border passing through the dialects since the Francia. In addition, two dialects situated in Slovene did not evolve from Slovene. The Čičarija dialect is a Chakavian dialect and parts of White Carniola were populated by Serbs during the Turkish invasion and therefore Shtokavian is spoken there.

Burgenland Croatian is a regional variety of the Chakavian dialect of Croatian spoken in Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia. Burgenland Croatian is recognized as a minority language in the Austrian state of Burgenland, where it is spoken by 19,412 people according to official reports (2001). Many of the Burgenland Croatian speakers in Austria also live in Vienna and Graz, due to the process of urbanization, which is mostly driven by the poor economic situation of large parts of Burgenland.

The Serb-Catholic movement in Dubrovnik was a cultural and political movement of people from Dubrovnik who, while Catholic, declared themselves Serbs, while Dubrovnik was part of the Habsburg-ruled Kingdom of Dalmatia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially spearheaded by intellectuals who espoused strong pro-Serbian sentiments, there were two prominent incarnations of the movement: an early pan-Slavic phase under Matija Ban and Medo Pucić that corresponded to the Illyrian movement, and a later, more Serbian nationalist group that was active between the 1880s and 1908, including a large number of Dubrovnik intellectuals at the time. The movement, whose adherents are known as Serb-Catholics or Catholic Serbs, largely disappeared with the creation of Yugoslavia.

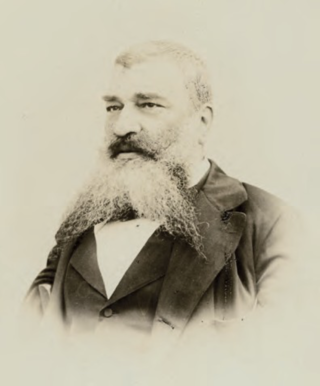

Luko Zore was a philologist and Slavist from Dubrovnik. He was one of the leaders of the opposition to Austro-Hungarian Empire and Italy in Dubrovnik and a member of the Serb Catholic movement in Dubrovnik. Later in life he lived in Montenegro.

The Encyclopedia of Yugoslavia or Yugoslavika was the national encyclopedia of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Published under the auspices of the Yugoslav Lexicographical Institute in Zagreb and overseen by Miroslav Krleža, it is a prominent source and comprehensive reference work about Yugoslavia and related topics.

Bible translations into Serbian started to appear in fragments in the 11th century. Efforts to make a complete translation started in the 16th century. The first published complete translations were made in the 19th century.

Bible translations into Croatian started to appear in fragments in the 14th century. Efforts to make a complete translation started in the 16th century. The first published complete translations were made in the 19th century.

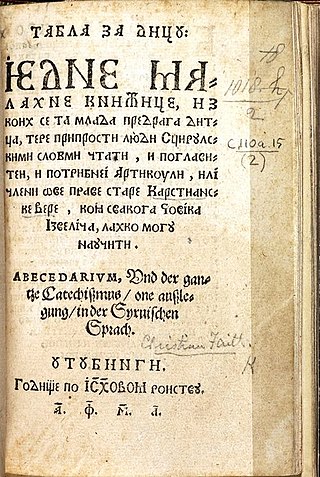

Jovan Maleševac was a Serbian Orthodox monk and scribe who collaborated in 1561 with the Slovene Protestant reformer Primož Trubar to print religious books in Cyrillic. Between 1524 and 1546, Maleševac wrote five liturgical books in Church Slavonic at Serbian Orthodox monasteries in Herzegovina and Montenegro. He later settled in the region of White Carniola, in present-day Slovenia. In 1561, he was engaged by Trubar to proof-read Cyrillic Protestant liturgical books produced in the South Slavic Bible Institute in Urach, Germany, where he stayed for five months.

Benedikt Benko Vinković was a Croatian prelate of the Catholic Church who served as the bishop of Pécs from 1630 to 1637 and the bishop of Zagreb from 1637 to his death in 1642.

Stipan/Stjepan Konzul Istranin, or Stephanus Consul, was a 16th-century Croatian Protestant reformator who authored and translated religious books to Čakavian dialect. Istranin was the most important Croatian Protestant writer.

Antun Aleksandrović Dalmatin was 16th century translator and publisher of Protestant liturgical books.

Hans von Ungnad (1493–1564) was 16th-century Habsburg nobleman who was best known as founder of the South Slavic Bible Institute established to publish Protestant books translated to South Slavic languages.

Matija Popović was 16th-century Serbian Orthodox priest from Ottoman Bosnia. Popović was printer in the South Slavic Bible Institute.

Dimitrije Ljubavić was a Serbian Orthodox deacon, humanist, writer and printer who together with German reformer Philip Melanchthon initiated the first formal contact between the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Lutherans in 1559 when Ljubavić took a copy of the Augsburg Confession to Patriarch Joasaph II of Constantinople. He is also referred to as Demetrios Mysos or Demetrius Mysos in Lutheran and other Western books.

Juraj Juričić, was a Croatian Protestant preacher and translator. Born in Croatia, Juričić translated and wrote in German, Slovenian and Croatian. In his Slovenian translations there are many elements of Croatian.

Juraj Cvečić,, was an Istrian Croatian translator, preacher and editor of Protestant books.

Ivan Paleček was a Croatian and Yugoslavian politician and lawyer.