Pedro Calderón de la Barca y Barreda González de Henao Ruiz de Blasco y Riaño was a Spanish dramatist, poet, writer and knight of the Order of Santiago. He is known as one of the most distinguished Baroque writers of the Spanish Golden Age, especially for his plays.

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist. He was one of the key figures in the Spanish Golden Age of Baroque literature. His reputation in the world of Spanish literature is second only to that of Miguel de Cervantes, while the sheer volume of his literary output is unequalled, making him one of the most prolific authors in the history of literature. He was nicknamed "The Phoenix of Wits" and "Monster of Nature" by Cervantes because of his prolific nature.

The Spanish Golden Age is a period of flourishing in arts and literature in Spain, coinciding with the political rise of the Spanish Empire under the Catholic Monarchs of Spain and the Spanish Habsburgs. The greatest patron of Spanish art and culture during this period was King Philip II (1556–1598), whose royal palace, El Escorial, invited the attention of some of Europe's greatest architects and painters such as El Greco, who infused Spanish art with foreign styles and helped create a uniquely Spanish style of painting. It is associated with the reigns of Isabella I, Ferdinand II, Charles V, Philip II, Philip III, and Philip IV, when Spain was the most powerful country in the world.

Lope de Rueda (c.1505<1510–1565) was a Spanish dramatist and author, regarded by some as the best of his era. A versatile writer, he also wrote comedies, farces, and pasos. He was the precursor to what is considered the golden age of Spanish literature.

Zan Ganassa was the stage name of an early actor-manager of Commedia dell'arte, whose company was one of the first to tour outside Italy. Ganassa's real name was probably Alberto Naseli.

Entremés, is a short, comic theatrical performance of one act, usually played during the interlude of a performance of a long dramatic work, in the 16th and 17th centuries in Spain. Later, it became the sainete.

Autos sacramentales are a form of dramatic literature which is unique to Spain and Hispanic America, though in some respects similar in character to the old Morality plays of England.

Juan de la Cueva de Garoza (1543–1612) was a Spanish dramatist and poet. He was born in Seville to an aristocratic family; his younger brother Claudio, with whom he spent some time in Guadalajara, Mexico, went on to become an archdeacon and inquisitor. He was acquainted with a number of major contemporary intellectual figures, including Fernando de Herrera and Juan de Mal Lara, and took part in the Casa de Pilatos literary academy in Seville. After his return to Spain in 1577, he began writing for the stage and produced a total of ten comedies and four tragedies. He appears never to have married, though some of his poetical works are dedicated to a Felipa de la Paz. After apparently spending some time in Cuenca after 1610, he died in Granada in 1612.

A loa is a short theatrical piece, a prologue, written to introduce plays of the Spanish Golden Age or Siglo de Oro during the 16th and 17th centuries. These plays included comedias and autos sacramentales. The main purposes for the loa included initially capturing the interest of the audience, pleading for their attention throughout the play, and setting the mood for the rest of the performance. This Spanish prologue is specifically characterized by praise and laudatory language for various people and places, often the royal court for example, to introduce the full-length play. The loa was also popular with Latin American or "New World" playwrights during the 17th and 18th centuries through Spanish colonization.

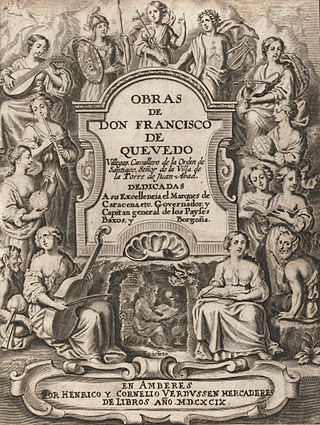

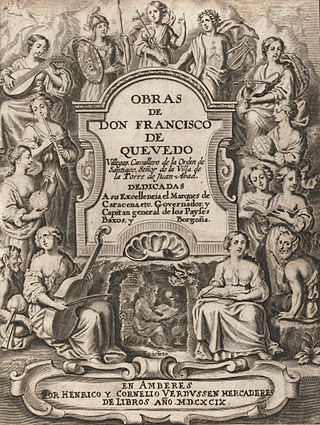

Spanish Baroque literature is the literature written in Spain during the Baroque, which occurred during the 17th century in which prose writers such as Baltasar Gracián and Francisco de Quevedo, playwrights such as Lope de Vega, Tirso de Molina, Calderón de la Barca and Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, or the poetic production of the aforementioned Francisco de Quevedo, Lope de Vega and Luis de Góngora reached their zenith. Spanish Baroque literature is a period of writing which begins approximately with the first works of Luis de Góngora and Lope de Vega, in the 1580s, and continues into the late 17th century.

The history of theatre charts the development of theatre over the past 2,500 years. While performative elements are present in every society, it is customary to acknowledge a distinction between theatre as an art form and entertainment, and theatrical or performative elements in other activities. The history of theatre is primarily concerned with the origin and subsequent development of the theatre as an autonomous activity. Since classical Athens in the 5th century BC, vibrant traditions of theatre have flourished in cultures across the world.

Teatro Español is a public theatre administered by the Government of Madrid, Spain. The original location was an open-air theatre in medieval times, where short performances and some theatrical pieces, which became part of famous classical literature in later years, were staged. Its establishment was authorized by a royal decree of Philip II in 1565.

Corral de comedias is a type of open-air theatre specific to Spain. In Spanish all secular plays were called comedias, which embraced three genres: tragedy, drama, and comedy itself. During the Spanish Golden Age, corrals became popular sites for theatrical presentations in the early 16th century when the theatre took on a special importance in the country. The performance was held in the afternoon and lasted two to three hours, there being no intermission, and few breaks. The entertainment was continuous, including complete shows with parts sung and danced. All spectators were placed according to their sex and social status.

Corral de comedias de Almagro is located at Plaza Mayor in Almagro, Castile-La Mancha, Spain. The building is the best preserved example of the corral de comedias of the 17th century.

Punishment without Vengeance is a 1631 tragedy written by the Spanish playwright Lope de Vega at the age of 68, centred on adultery and a near-incestuous relationship between step-mother and step-son. It is regarded as one of Lope’s supreme achievements.

The Steel of Madrid is a 1608 play by the Spanish writer Lope de Vega, considered part of the Spanish Golden Age of literature.

John Rutter Chorley was an English author, bibliophile, and Hispanist.

Ana Caro de Mallén is a poet and playwright of the Spanish Golden Age.