Related Research Articles

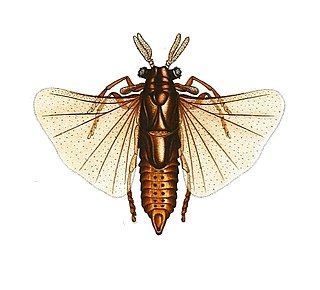

The Strepsiptera are an order of insects with eleven extant families that include about 600 described species. They are endoparasites of other insects, such as bees, wasps, leafhoppers, silverfish, and cockroaches. Females of most species never emerge from the host after entering its body, finally dying inside it. The early-stage larvae do emerge because they must find an unoccupied living host, and the short-lived males must emerge to seek a receptive female in her host. They are believed to be most closely related to beetles, from which they diverged 300–350 million years ago, but do not appear in the fossil record until the mid-Cretaceous around 100 million years ago.

Hemiptera is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from 1 mm (0.04 in) to around 15 cm (6 in), and share a common arrangement of piercing-sucking mouthparts. The name "true bugs" is often limited to the suborder Heteroptera.

The Cimicidae are a family of small parasitic bugs that feed exclusively on the blood of warm-blooded animals. They are called cimicids or, loosely, bed bugs, though the latter term properly refers to the most well-known member of the family, Cimex lectularius, the common bed bug and its tropical relation Cimex hemipterus. The family contains over 100 species. Cimicids appeared in the fossil record in the Cretaceous period. When bats evolved in the Eocene, Cimicids switched hosts and now feed mainly on bats or birds. Members of the group have colonised humans on three occasions.

Penis fencing is a mating behavior engaged in by many species of flatworm, such as Pseudobiceros hancockanus. Species which engage in the practice are hermaphroditic; each individual has both egg-producing ovaries and sperm-producing testes.

Sexual conflict or sexual antagonism occurs when the two sexes have conflicting optimal fitness strategies concerning reproduction, particularly over the mode and frequency of mating, potentially leading to an evolutionary arms race between males and females. In one example, males may benefit from multiple matings, while multiple matings may harm or endanger females, due to the anatomical differences of that species. Sexual conflict underlies the evolutionary distinction between male and female.

Idiosepius paradoxus, also known as the northern pygmy squid, is a species of pygmy squid native to the western Pacific Ocean. This species can be found inhabiting shallow, inshore waters around central China, South Korea, and Japan.

Traumatic insemination, also known as hypodermic insemination, is the mating practice in some species of invertebrates in which the male pierces the female's abdomen with his aedeagus and injects his sperm through the wound into her abdominal cavity (hemocoel). The sperm diffuses through the female's hemolymph, reaching the ovaries and resulting in fertilization.

Xenos vesparum is a parasitic insect species of the order Strepsiptera that are endoparasites of paper wasps in the genus Polistes that was first described in 1793. Like other members of this family, X. vesparum displays a peculiar lifestyle, and demonstrates extensive sexual dimorphism.

Cimex is a genus of insects in the family Cimicidae. Cimex species are ectoparasites that typically feed on the blood of birds and mammals. Two species, Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus, are known as bed bugs and frequently feed on humans, although other species may parasitize humans opportunistically. Species that primarily parasitize bats are known as bat bugs.

Afrocimex constrictus, also called the African bat bug, is an insect parasite of Egyptian fruit bats in bat caves in East Africa. Population sizes can comprise millions of individuals and in a cave there can be one to 15 bugs per bat. It was estimated that adult African bat bugs feed approximately once per week thus withdrawing 1-28 microlitre blood per day per bat.

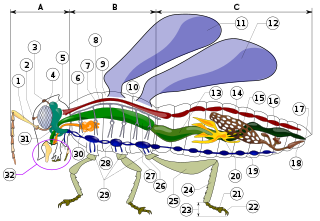

Insect morphology is the study and description of the physical form of insects. The terminology used to describe insects is similar to that used for other arthropods due to their shared evolutionary history. Three physical features separate insects from other arthropods: they have a body divided into three regions, three pairs of legs, and mouthparts located outside of the head capsule. This position of the mouthparts divides them from their closest relatives, the non-insect hexapods, which include Protura, Diplura, and Collembola.

An intromittent organ is any external organ of a male organism that is specialized to deliver sperm during copulation. Intromittent organs are found most often in terrestrial species, as most non-mammalian aquatic species fertilize their eggs externally, although there are exceptions. For many species in the animal kingdom, the male intromittent organ is a hallmark characteristic of internal fertilization.

Female sperm storage is a biological process and often a type of sexual selection in which sperm cells transferred to a female during mating are temporarily retained within a specific part of the reproductive tract before the oocyte, or egg, is fertilized. This process takes place in some species of animals, but not in humans. The site of storage is variable among different animal taxa and ranges from structures that appear to function solely for sperm retention, such as insect spermatheca and bird sperm storage tubules, to more general regions of the reproductive tract enriched with receptors to which sperm associate before fertilization, such as the caudal portion of the cow oviduct containing sperm-associating annexins. Female sperm storage is an integral stage in the reproductive process for many animals with internal fertilization. It has several documented biological functions including:

Sexual antagonistic co-evolution is the relationship between males and females where sexual morphology changes over time to counteract the opposite's sex traits to achieve the maximum reproductive success. This has been compared to an arms race between sexes. In many cases, male mating behavior is detrimental to the female's fitness. For example, when insects reproduce by means of traumatic insemination, it is very disadvantageous to the female's health. During mating, males will try to inseminate as many females as possible, however, the more times a female's abdomen is punctured, the less likely she is to survive. Females that possess traits to avoid multiple matings will be more likely to survive, resulting in a change in morphology. In males, genitalia is relatively simple and more likely to vary among generations compared to female genitalia. This results in a new trait that females have to avoid in order to survive.

Jacques Carayon was a French entomologist, best known for his pioneering research into traumatic insemination. Carayon was Chairman of Entomology at the National Museum in Paris from 1975 to 1985.

Cryptic female choice is a form of mate choice which occurs both in pre and post copulatory circumstances when females in certain species use physical or chemical mechanisms to control a male's success of fertilizing their ova or ovum; i.e. by selecting whether sperm are successful in fertilizing their eggs or not. It occurs in internally-fertilizing species and involves differential use of sperm by females when sperm are available in the reproductive tract.

Primicimex is a monotypic genus of ectoparasitic bed bugs in the family Cimicidae, the only species being Primicimex cavernis, which is both the largest cimicid, and the most primitive one. It feeds on bats and was described from Ney Cave in Medina County, Texas but has since been found in four other caves in Guatemala, Mexico, and southern United States.

Lyctocoridae is a reconstituted family of bugs, formerly classified within the minute pirate bugs of the family Anthocoridae. It is widely distributed, with one species, being cosmopolitan.

Lasiochilinae is a subfamily of bugs, in the family Anthocoridae; some authorities place this at family level: "Lasiochilidae". It is most diverse in tropical areas, especially in the New World.

Michael 'Mike' Siva-Jothy is an entomologist in the UK, he is Professor of Entomology at the University of Sheffield.

References

- ↑ Siva-Jothy, M. T. (2006) "Trauma, disease and collateral damage: conflict in cimicids," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 361, 269–275.

- 1 2 Edward H. Morrow & Goran Arnqvist (2003). "Costly traumatic insemination and a female counter-adaptation in bed bugs" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B . 270 (1531): 2377–2381. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2514. PMC 1691516 . PMID 14667354. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Reinhardt, K., Naylor, R. & Siva-Jothy, M. T. (2003) "Reducing a cost of traumatic insemination: female bedbugs evolve a unique organ," Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 270, 2371–2375.

- ↑ Carayon, J. (1966) Traumatic insemination and the paragenital system. In Monograph of Cimicidae (Hemiptera—Heteroptera) (ed. R. L. Usinger), pp. 81–166. College Park, MD: Entomological Society of America.

- ↑ Ryne, C. (2009) "Homosexual interactions in bed bugs: alarm pheromones as male recognition signals," Animal Behaviour, 78, 1471–1475.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Reinhardt, K. & Siva-Jothy, M. T. (2007) "Biology of the bed bugs (Cimicidae)," Annual Review of Entomology, 52, 351–374.

- 1 2 Siva-Jothy MT (2006-02-28). "Trauma, disease and collateral damage: conflict in cimicids". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 361 (1466): 269–75. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1789. PMC 1569606 . PMID 16612886.