Related Research Articles

The Tamil people, also known as Tamilar, or simply Tamils, are a Dravidian ethno-linguistic group who trace their ancestry mainly to India’s southern state of Tamil Nadu, union territory of Puducherry and to Sri Lanka. Tamils who speak the Tamil Language and are born in Tamil clans are considered Tamilians. Tamils constitute 5.9% of the population in India, 15% in Sri Lanka, 7% in Malaysia, 6% in Mauritius, and 5% in Singapore.

The caste systems in Sri Lanka are social stratification systems found among the ethnic groups of the island since ancient times. The models are similar to those found in Continental India, but are less extensive and important for various reasons, although the caste systems still play an important and at least symbolic role in religion and politics. Sri Lanka is often considered to be a casteless or caste-blind society by Indians.

Koneswaram Temple of Trincomalee or Thirukonamalai Konesar Temple – The Temple of the Thousand Pillars and Dakshina-Then Kailasam is a classical-medieval Hindu temple complex in Trincomalee, a Hindu religious pilgrimage centre in Eastern Province, Sri Lanka. The most sacred of the Pancha Ishwarams of Sri Lanka, it was built significantly during the ancient period on top of Konesar Malai, a promontory overlooking Trincomalee District, Gokarna bay and the Indian Ocean. The monument contains its main shrine to Shiva in the form Kona-Eiswara, shortened to Konesar.

Vellalar is a generic Tamil term used primarily to refer to various castes who traditionally pursued agriculture as a profession in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and northeastern parts of Sri Lanka. The Vellalar are members of several endogamous castes such as the numerically strong Arunattu Vellalar, Chozhia Vellalar, Karkarthar Vellalar, Kongu Vellalar, Thuluva Vellalar and Sri Lankan Vellalar.

The Jaffna Kingdom, also known as Kingdom of Aryachakravarti, was a historical kingdom of what today is northern Sri Lanka. It came into existence around the town of Jaffna on the Jaffna peninsula and was traditionally thought to have been established after the invasion of Kalinga Magha from Kalinga in India. Established as a powerful force in the north, northeast and west of the island, it eventually became a tribute-paying feudatory of the Pandyan Empire in modern South India in 1258, gaining independence when the last Pandyan ruler of Madurai was defeated and expelled in 1323 by Malik Kafur, the army general of the Delhi Sultanate. For a brief period in the early to mid-14th century it was an ascendant power in the island of Sri Lanka, to which all regional kingdoms accepted subordination. However, the kingdom was overpowered by the rival Kotte Kingdom around 1450 when it was invaded by Prince Sapumal under the orders of Parakramabahu VI.

Sri Lankan Tamils, also known as Ceylon Tamils or Eelam Tamils, are Tamils native to the South Asian island state of Sri Lanka. Today, they constitute a majority in the Northern Province, live in significant numbers in the Eastern Province and are in the minority throughout the rest of the country. 70% of Sri Lankan Tamils in Sri Lanka live in the Northern and Eastern provinces.

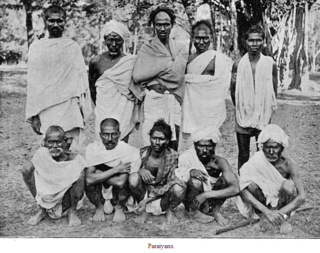

Paraiyar, or Parayar or Maraiyar, is a caste group found in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala, and Sri Lanka.

Tamiḻakam refers to the geographical region inhabited by the ancient Tamil people, covering the southernmost region of the Indian subcontinent. Tamilakam covered today's Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry, Lakshadweep and southern parts of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. Traditional accounts and the Tolkāppiyam referred to these territories as a single cultural area, where Tamil was the natural language and permeated the culture of all its inhabitants. The ancient Tamil country was divided into kingdoms. The best known among them were the Cheras, Cholas, Pandyans and Pallavas. During the Sangam period, Tamil culture began to spread outside Tamilakam. Ancient Tamil settlements were also established in Sri Lanka and the Maldives (Giravarus).

Koviyar is a Tamil caste found in Sri Lanka. They are traditional agriculturalists and temple workers. Kattavarayan as caste deity is observed by the Koviar.

Karaiyar is a Sri Lankan Tamil caste found mainly on the northern and eastern coastal areas of Sri Lanka, and globally among the Tamil diaspora.

Kayts, is one of the important villages in Velanai Island which is a small island off the coast of the Jaffna Peninsula in northern Sri Lanka. There are number of other villages within the Velanai Islands such as Allaippiddi, Mankumpan, Velanai, Saravanai, Puliyankoodal, Suruvil, Naranthanai, Karampon and Melinchimunai.

Sri Lankan Vellalar is a caste in Sri Lanka, predominantly found in the Jaffna peninsula and adjacent Vanni region, who comprise about half of the Sri Lankan Tamil population. They were traditionally involved in agriculture, but also included merchants, landowners and temple patrons. They also form part of the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora.

Nainativu, is a small but notable island off the coast of Jaffna Peninsula in the Northern Province, Sri Lanka. The name of the island alludes to the folklore inhabitants, the Naga people. It is home to the Hindu shrine of Nagapooshani Amman Temple; one of the prominent 64 Shakti Peethas, and the Buddhist shrine Nagadeepa Purana Viharaya.

Vanniar or Vanniyar was a title borne by chiefs in medieval Sri Lanka who ruled in the Chiefdom of Vavuni regions as tribute payers to the Jaffna vassal state. There are a number of origin theories for the feudal chiefs, coming from an indigenous formation. The most famous of the Vavni chieftains was Pandara Vannian, known for his resistance against the British colonial power.

The Vanni chieftaincies or Vanni principalities was a region between Anuradhapura and Jaffna, but also extending to along the eastern coast to Panama and Yala, during the Transitional and Kandyan periods of Sri Lanka. The heavily forested land was a collection of chieftaincies of principalities that were a collective buffer zone between the Jaffna Kingdom, in the north of Sri Lanka, and the Sinhalese kingdoms in the south. Traditionally the forest regions were ruled by Vedda rulers. Later on, the emergence of these chieftaincies were a direct result of the breakdown of central authority and the collapse of the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa in the 13th century, as well as the establishment of the Jaffna Kingdom in the Jaffna Peninsula. Control of this area was taken over by dispossessed Sinhalese nobles and chiefs of the South Indian military of Māgha of Kalinga (1215–1236), whose 1215 invasion of Polonnaruwa led to the kingdom's downfall. Sinhalese chieftaincies would lay on the northern border of the Sinhalese kingdom while the Tamil chieftaincies would border the Jaffna Kingdom and the remoter areas of the eastern coast, north western coast outside of the control of either kingdom.

The Naga people are believed by some to be an ancient tribe who once inhabited Sri Lanka and various parts of Southern India. There are references to Nagas in several ancient texts such as Mahavamsa, Manimekalai, Mahabharata and also in other Sanskrit and Pali literature. They were generally represented as a class of super-humans taking the form of serpents who inhabit a subterranean world.

When to date the start of the history of the Jaffna kingdom is debated among historians.

Kulakkottan was an early Chola king and descendant of Manu Needhi Cholan who was mentioned in chronicles such as the Yalpana Vaipava Malai and stone inscriptions like Konesar Kalvettu. His name Kulakkottan means 'builder of tank and temple'.

Madapalli is a caste found mainly in the northern part of Sri Lanka. Found today as a subcaste of the Sri Lankan Vellalar, the Madapallis were considered an independent caste until recently.

Sri Lankan Pallar is a Tamil caste found in northern and eastern Sri Lanka. They are traditionally involved in agriculture and were also involved in toddy tapping and artisanal fishing.

References

- 1 2 3 David, Kenneth (2011-06-03). The New Wind: Changing Identities in South Asia. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 191, 203. ISBN 9783110807752.

- ↑ Shankar, S. (2012-07-02). Flesh and Fish Blood: Postcolonialism, Translation, and the Vernacular. University of California Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780520272521.

- ↑ Jesudasan, Hephzibah; Samuel, G. John; Thiagarajan, P. (1999). Count-down from Solomon, Or, The Tamils Down the Ages Through Their Literature: Caṅkam and the aftermath. Chennai, Tamil Nadu: Institute of Asian Studies. p. 133.

- ↑ Sykes, Jim (2018-08-31). The Musical Gift: Sonic Generosity in Post-War Sri Lanka. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190912031.

- 1 2 Pillay, Kolappa Pillay Kanakasabhapathi (1979). Studies in Indian history: with special reference to Tamil Nādu. p. 412.

- ↑ Devi, R. Leela (1986). History of Kerala. Vidyarthi Mithram Press & Book Depot. p. 102.

- ↑ Kōtilmoḻiyaṉ, Ciṉ (1988). Tolkāppiyattil cātineṟi (in Tamil). Vacanta Celvi Patippakam. p. 80.

சாம்பு என்னும் சொல் 'பறை' என்னும் பொருளுடையது: The word cāmpu share meaning with the word "paṟai".

- ↑ Singh, Kumar Suresh; India, Anthropological Survey of (2002). People of India. Anthropological Survey of India. p. 1203. ISBN 978-81-85938-99-8.

- ↑ Deliège, Robert (1997-01-01). The World of the "untouchables": Paraiyars of Tamil Nadu. Oxford University Press. p. 134. ISBN 9780195642308.

- ↑ K. Sivathamby (1981). Drama in Ancient Tamil Society. New Century Book House. p. 201.

- ↑ The Secret Garland: Āṇṭāls Tiruppāvai and Nācciyār Tirumoli. Oxford University Press. 2010. p. 19. ISBN 9780195391756.

- ↑ Vincentnathan, Lynn (1987). Harijan Subculture and Self-esteem Management in a South Indian Community. University of Wisconsin-Medison. p. 42.

- 1 2 Parasher-Sen, Aloka (2004). Subordinate and Marginal Groups in Early India. Oxford University Press. pp. 131, 135, 141. ISBN 9780195690897.

- ↑ Nayagam, Xavier S. Thani (1971). Thirumathi Sornammal Endowment Lectures on Tirukkural, 1959-60 to 1968-69. University of Madras 1971. p. 212.

- ↑ Moffatt, Michael (2015-03-08). An Untouchable Community in South India: Structure and Consensus. Princeton University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9781400870363.

- ↑ Journal of the Epigraphical Society of India. Epigraphical Society of India. 1999. p. 95.

- ↑ Orr, Leslie C. (2000-03-09). Donors, Devotees, and Daughters of God: Temple Women in Medieval Tamilnadu. Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780195356724.

- ↑ Parasher-Sen, Aloka (2004). Subordinate and Marginal Groups in Early India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195665420.

- ↑ University, Vijaya Ramaswamy, Jawaharlal Nehru (2017-08-25). Historical Dictionary of the Tamils. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 153–154. ISBN 9781538106860.

- ↑ Stein, Burton (1994). Peasant State and Society in Medieval South India. Oxford University Press. pp. 188–189.

- 1 2 3 4 Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. University of Jaffna: Thillimalar Ragupathy. pp. 166–167, 210.

- 1 2 Raghavan, M. D. (1971). Tamil culture in Ceylon: a general introduction. Kalai Nilayam. p. 181.

- ↑ Arasaratnam, S. (1981-07-01). "Social History of a Dominant Caste Society: The Vellalar of North Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in the 18th Century". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 18 (3–4): 377–391. doi:10.1177/001946468101800306. ISSN 0019-4646. S2CID 143603755.

- ↑ Holt, John (2011-04-13). The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. p. 205. ISBN 9780822349822.

- ↑ Peebles, Patrick (2001-01-01). The Plantation Tamils of Ceylon. A&C Black. p. 68. ISBN 9780718501549.

- ↑ Bass, Daniel (2004). A place on the plantations: up-country Tamil ethnicity in Sri Lanka. University of Michigan. p. 29.

- ↑ The Ceylon Antiquary and Literary Register. 1924.

- ↑ Pillay, Kolappa Pillay Kanakasabhapathi (1977). The Caste System in Tamil Nadu. University of Madras. p. 33.

- 1 2 Sykes, Jim (2018-08-31). The Musical Gift: Sonic Generosity in Post-War Sri Lanka. Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 9780190912048.

- ↑ Mcgilvray, Dennis B. (1983). "Paraiyar Drummers of Sri Lanka: consensus and constraint in an untouchable caste". American Ethnologist. 10 (1): 97–115. doi: 10.1525/ae.1983.10.1.02a00060 . ISSN 1548-1425.

- ↑ Leach, E. R. (1960). Aspects of Caste in South India, Ceylon and North-West Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 64, 73. ISBN 9780521096645.

- ↑ Ponnambalam, Raghupathy. Tamil Social Formation in Sri Lanka A Historical Outline. University of Jaffna: Institute of Research and Development. p. 2.