Related Research Articles

Swahili, also known by its local name Kiswahili, is a Bantu language originally spoken by the Swahili people, who are found primarily in Tanzania, Kenya, and Mozambique. Estimates of the number of Swahili speakers, including both native and second-language speakers, vary widely. They generally range from 150 million to 200 million; with most of its native speakers residing in Tanzania and Kenya.

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to the south; Zambia to the southwest; and Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west. According to the 2022 national census, Tanzania has a population of around 62 million, making it the most populous country located entirely south of the equator.

The modern-day African Great Lakes state of Tanzania dates formally from 1964, when it was formed out of the union of the much larger mainland territory of Tanganyika and the coastal archipelago of Zanzibar. The former was a colony and part of German East Africa from the 1880s to 1919 when, under the League of Nations, it became a British mandate. It served as a British mir II]], providing financial help, munitions, and soldiers. In 1947, Tanganyika became a United Nations Trust Territory under British administration, a status it kept until its independence in 1961. The island of Zanzibar thrived as a trading hub, successively controlled by the Portuguese, the Sultanate of Oman, and then as a British protectorate by the end of the nineteenth century.

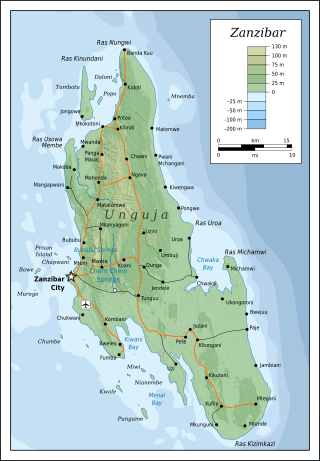

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small islands and two large ones: Unguja and Pemba Island. The capital is Zanzibar City, located on the island of Unguja. Its historic centre, Stone Town, is a World Heritage Site.

"Mungu ibariki Afrika" is the national anthem of Tanzania. It is a Swahili language version of Enoch Sontonga's Xhosa language hymn "Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika".

The Swahili people comprise mainly Bantu, Afro-Arab, and Comorian ethnic groups inhabiting the Swahili coast, an area encompassing the East African coast across southern Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and northern Mozambique, and various archipelagos off the coast, such as Zanzibar, Lamu, and the Comoro Islands.

Johann Ludwig Krapf was a German missionary in East Africa, as well as an explorer, linguist, and traveler. Krapf played an important role in exploring East Africa with Johannes Rebmann. They were the first Europeans to see Mount Kenya with the help of Akamba who dwelled at its slopes and Kilimanjaro. Ludwig Krapf visited Ukambani, the homeland of the Kamba people, in 1849 and again in 1850. He successfully translated the New Testament to the Kamba language. Krapf also played a key role in exploring the East African coastline, especially in Mombasa.

Unyamwezi is a historical region in what is now Tanzania, around the modern city of Tabora to the south of Lake Victoria and east of Lake Tanganyika. It lay on the trade route from the coast to Lake Tanganyika and to the kingdoms to the west of Lake Victoria. The various peoples of the region were known as long-distance traders, providing porters for caravans and arranging caravans in their own right. At first the main trade was in ivory, but later slaving became more important.

Unguja is the largest and most populated island of the Zanzibar archipelago, in Tanzania.

Swahili literature is literature written in the Swahili language, particularly by Swahili people of the East African coast and the neighboring islands. It may also refer to literature written by people who write in the Swahili language. It is an offshoot of the Bantu culture.

Baraza la Kiswahili la Taifa is a Tanzanian institution responsible with regulating and promoting the Kiswahili language.

Digo (Chidigo) is a Bantu language spoken primarily along the East African coast between Mombasa and Tanga by the Digo people of Kenya and Tanzania. The ethnic Digo population has been estimated at around 360,000, the majority of whom are presumably speakers of the language. All adult speakers of Digo are bilingual in Swahili, East Africa's lingua franca. The two languages are closely related, and Digo also has much vocabulary borrowed from neighbouring Swahili dialects.

Johannes Rebmann, also sometimes anglicised as John Rebman, was a German missionary, linguist, and explorer credited with feats including being the first European, along with his colleague Johann Ludwig Krapf, to enter Africa from the Indian Ocean coast. In addition, he was the first European to find Kilimanjaro. News of Rebmann's discovery was published in the Church Missionary Intelligencer in May 1849, but disregarded as mere fantasy for the next twelve years. The Geographical Society of London held that snow could not possibly occur let alone persist in such latitudes and considered the report to be the hallucination of a malaria-stricken missionary. It was only in 1861 that researchers began their efforts to measure Kilimanjaro. Expeditions to Tanganyika between 1861 and 1865, led by the German Baron Karl Klaus von der Decken, confirmed Rebmann's report. Together with his colleague Johann Ludwig Krapf they were also the first Europeans to visit and report Mount Kenya. Their work there is also thought to have had effects on future African expeditions by Europeans, including the exploits of Sir Richard Burton, John Hanning Speke, and David Livingstone.

Up to the second half of the 20th century, Tanzanian literature was primarily oral. Major oral literary forms include folktales, poems, riddles, proverbs, and songs. The majority of the oral literature in Tanzania that has been recorded is in Swahili, though each of the country's languages has its own oral tradition. The country's oral literature is currently declining because of social changes that make transmission of oral literature more difficult and because of the devaluation of oral literature that has accompanied Tanzania's development. Tanzania's written literary tradition has produced relatively few writers and works; Tanzania does not have a strong reading culture, and books are often expensive and hard to come by. Most Tanzanian literature is orally performed or written in Swahili, and a smaller number of works have been published in English. Major figures in Tanzanian modern literature include Shaaban Robert, Muhammed Said Abdulla, Aniceti Kitereza, Ebrahim Hussein, Abdulrazak Gurnah and Penina Muhando.

Lake Uniamési or the Uniamesi Sea was the name given by missionaries in the 1840s and 1850s to a huge lake or inland sea they supposed to lie within a region of Central East Africa with the same name.

Taasisi ya Taaluma za Kiswahili, known by its acronym TATAKI, is a research body dedicated to the research of the Kiswahili language and literature at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

Francis Roger Hodgson was a British Anglican missionary and Bible translator in Zanzibar, and later a parish priest in Devon, England.

Arthur Cornwallis Madan (1846–1917) was a British linguist and Anglican missionary who became famous for his research on African languages and his Swahili dictionaries.

Mrima or Mrima Coast is the traditional name for the part of the East African coast facing Zanzibar. The inhabitants were often called "Wamrima" or Mrima people even though they could belong to different tribes and language groups.

Cecil Majaliwa was a former slave from Zanzibar who became the first African to be ordained as a priest in what is now Tanzania. After being freed, he was educated in Zanzibar and England by the Universities' Mission to Central Africa. He was highly successful during eleven years as an Anglican missionary in the south of the country. However, the European leaders of the mission downplayed his achievements and failed to promote him.

References

- Robinson, Morgan J. (2024-01-30). "History of the Standard Swahili Language". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.1012. ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4 . Retrieved 2024-03-31.

- Robinson, Morgan J. (2022). A language for the world: the standardization of Swahili. New African histories. Athens: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-4781-9.