In statistics, an estimator is a rule for calculating an estimate of a given quantity based on observed data: thus the rule, the quantity of interest and its result are distinguished. For example, the sample mean is a commonly used estimator of the population mean.

Frequentist probability or frequentism is an interpretation of probability; it defines an event's probability as the limit of its relative frequency in many trials. Probabilities can be found by a repeatable objective process. The continued use of frequentist methods in scientific inference, however, has been called into question.

A histogram is an approximate representation of the distribution of numerical data. The term was first introduced by Karl Pearson. To construct a histogram, the first step is to "bin" the range of values—that is, divide the entire range of values into a series of intervals—and then count how many values fall into each interval. The bins are usually specified as consecutive, non-overlapping intervals of a variable. The bins (intervals) must be adjacent and are often of equal size.

Probability is the branch of mathematics concerning numerical descriptions of how likely an event is to occur, or how likely it is that a proposition is true. The probability of an event is a number between 0 and 1, where, roughly speaking, 0 indicates impossibility of the event and 1 indicates certainty. The higher the probability of an event, the more likely it is that the event will occur. A simple example is the tossing of a fair (unbiased) coin. Since the coin is fair, the two outcomes are both equally probable; the probability of "heads" equals the probability of "tails"; and since no other outcomes are possible, the probability of either "heads" or "tails" is 1/2.

The word probability has been used in a variety of ways since it was first applied to the mathematical study of games of chance. Does probability measure the real, physical, tendency of something to occur, or is it a measure of how strongly one believes it will occur, or does it draw on both these elements? In answering such questions, mathematicians interpret the probability values of probability theory.

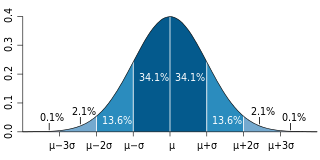

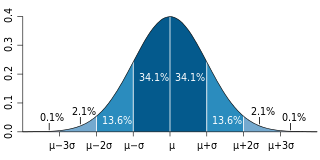

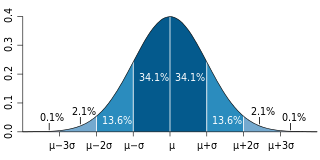

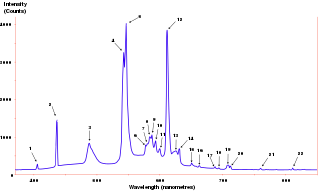

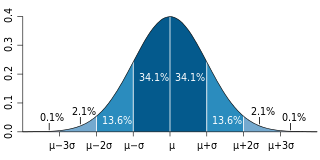

Probability theory is the branch of mathematics concerned with probability. Although there are several different probability interpretations, probability theory treats the concept in a rigorous mathematical manner by expressing it through a set of axioms. Typically these axioms formalise probability in terms of a probability space, which assigns a measure taking values between 0 and 1, termed the probability measure, to a set of outcomes called the sample space. Any specified subset of the sample space is called an event. Central subjects in probability theory include discrete and continuous random variables, probability distributions, and stochastic processes . Although it is not possible to perfectly predict random events, much can be said about their behavior. Two major results in probability theory describing such behaviour are the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem.

In probability theory and statistics, a probability distribution is the mathematical function that gives the probabilities of occurrence of different possible outcomes for an experiment. It is a mathematical description of a random phenomenon in terms of its sample space and the probabilities of events.

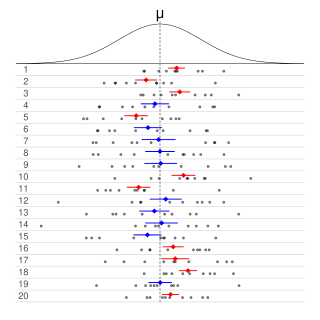

Statistical inference is the process of using data analysis to infer properties of an underlying distribution of probability. Inferential statistical analysis infers properties of a population, for example by testing hypotheses and deriving estimates. It is assumed that the observed data set is sampled from a larger population.

In probability theory and related fields, a stochastic or random process is a mathematical object usually defined as a family of random variables. Stochastic processes are widely used as mathematical models of systems and phenomena that appear to vary in a random manner. Examples include the growth of a bacterial population, an electrical current fluctuating due to thermal noise, or the movement of a gas molecule. Stochastic processes have applications in many disciplines such as biology, chemistry, ecology, neuroscience, physics, image processing, signal processing, control theory, information theory, computer science, cryptography and telecommunications. Furthermore, seemingly random changes in financial markets have motivated the extensive use of stochastic processes in finance.

In probability theory, the law of large numbers (LLN) is a theorem that describes the result of performing the same experiment a large number of times. According to the law, the average of the results obtained from a large number of trials should be close to the expected value and tends to become closer to the expected value as more trials are performed.

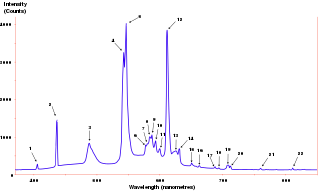

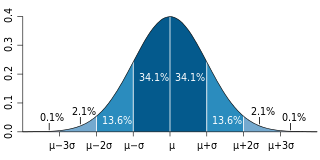

The power spectrum of a time series describes the distribution of power into frequency components composing that signal. According to Fourier analysis, any physical signal can be decomposed into a number of discrete frequencies, or a spectrum of frequencies over a continuous range. The statistical average of a certain signal or sort of signal as analyzed in terms of its frequency content, is called its spectrum.

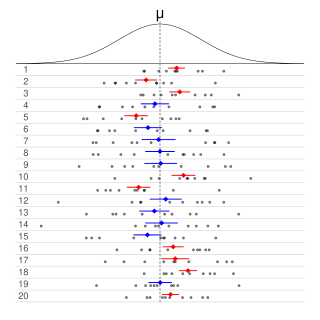

In frequentist statistics, a confidence interval (CI) is a range of estimates for an unknown parameter. A confidence interval is computed at a designated confidence level; the 95% confidence level is most common, but other levels, such as 90% or 99%, are sometimes used. The confidence level represents the long-run proportion of corresponding CIs that contain the true value of the parameter. For example, out of all intervals computed at the 95% level, 95% of them should contain the parameter's true value.

In probability theory, the law of the iterated logarithm describes the magnitude of the fluctuations of a random walk. The original statement of the law of the iterated logarithm is due to A. Ya. Khinchin (1924). Another statement was given by A. N. Kolmogorov in 1929.

This glossary of statistics and probability is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in the mathematical sciences of statistics and probability, their sub-disciplines, and related fields. For additional related terms, see Glossary of mathematics and Glossary of experimental design.

In applied mathematics, the Wiener–Khinchin theorem or Wiener–Khintchine theorem, also known as the Wiener–Khinchin–Einstein theorem or the Khinchin–Kolmogorov theorem, states that the autocorrelation function of a wide-sense-stationary random process has a spectral decomposition given by the power spectrum of that process.

Intuitively, an algorithmically random sequence is a sequence of binary digits that appears random to any algorithm running on a universal Turing machine. The notion can be applied analogously to sequences on any finite alphabet. Random sequences are key objects of study in algorithmic information theory.

In statistics, the frequency of an event is the number of times the observation occurred/recorded in an experiment or study. These frequencies are often depicted graphically or in tabular form.

In probability theory, conditional probability is a measure of the probability of an event occurring, given that another event has already occurred. This particular method relies on event B occurring with some sort of relationship with another event A. In this event, the event B can be analyzed by a conditional probability with respect to A. If the event of interest is A and the event B is known or assumed to have occurred, "the conditional probability of A given B", or "the probability of A under the condition B", is usually written as P(A|B) or occasionally PB(A). This can also be understood as the fraction of probability B that intersects with A: .