Significance of the moments

The nth raw moment (i.e., moment about zero) of a random variable with density function is defined by [2] The nth moment of a real-valued continuous random variable with density function about a value is the integral

It is possible to define moments for random variables in a more general fashion than moments for real-valued functions – see moments in metric spaces. The moment of a function, without further explanation, usually refers to the above expression with . For the second and higher moments, the central moment (moments about the mean, with c being the mean) are usually used rather than the moments about zero, because they provide clearer information about the distribution's shape.

Other moments may also be defined. For example, the nth inverse moment about zero is and the nth logarithmic moment about zero is

The nth moment about zero of a probability density function is the expected value of and is called a raw moment or crude moment. [3] The moments about its mean are called central moments; these describe the shape of the function, independently of translation.

If is a probability density function, then the value of the integral above is called the nth moment of the probability distribution. More generally, if F is a cumulative probability distribution function of any probability distribution, which may not have a density function, then the nth moment of the probability distribution is given by the Riemann–Stieltjes integral where X is a random variable that has this cumulative distribution F, and E is the expectation operator or mean. Whenthe moment is said not to exist. If the nth moment about any point exists, so does the (n − 1)th moment (and thus, all lower-order moments) about every point. The zeroth moment of any probability density function is 1, since the area under any probability density function must be equal to one.

| Moment ordinal | Moment | Cumulant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | Central | Standardized | Raw | Normalized | |

| 1 | Mean | 0 | 0 | Mean | — |

| 2 | — | Variance | 1 | Variance | 1 |

| 3 | — | — | Skewness | — | Skewness |

| 4 | — | — | (Non-excess or historical) kurtosis | — | Excess kurtosis |

| 5 | — | — | Hyperskewness | — | — |

| 6 | — | — | Hypertailedness | — | — |

| 7+ | — | — | — | — | — |

Standardized moments

The normalisednth central moment or standardised moment is the nth central moment divided by σn; the normalised nth central moment of the random variable X is

These normalised central moments are dimensionless quantities, which represent the distribution independently of any linear change of scale.

Notable moments

Mean

The first raw moment is the mean, usually denoted

Variance

The second central moment is the variance. The positive square root of the variance is the standard deviation

Skewness

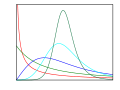

The third central moment is the measure of the lopsidedness of the distribution; any symmetric distribution will have a third central moment, if defined, of zero. The normalised third central moment is called the skewness, often γ. A distribution that is skewed to the left (the tail of the distribution is longer on the left) will have a negative skewness. A distribution that is skewed to the right (the tail of the distribution is longer on the right), will have a positive skewness.

For distributions that are not too different from the normal distribution, the median will be somewhere near μ − γσ/6; the mode about μ − γσ/2.

Kurtosis

The fourth central moment is a measure of the heaviness of the tail of the distribution. Since it is the expectation of a fourth power, the fourth central moment, where defined, is always nonnegative; and except for a point distribution, it is always strictly positive. The fourth central moment of a normal distribution is 3σ4.

The kurtosis κ is defined to be the standardized fourth central moment. (Equivalently, as in the next section, excess kurtosis is the fourth cumulant divided by the square of the second cumulant.) [4] [5] If a distribution has heavy tails, the kurtosis will be high (sometimes called leptokurtic); conversely, light-tailed distributions (for example, bounded distributions such as the uniform) have low kurtosis (sometimes called platykurtic).

The kurtosis can be positive without limit, but κ must be greater than or equal to γ2 + 1; equality only holds for binary distributions. For unbounded skew distributions not too far from normal, κ tends to be somewhere in the area of γ2 and 2γ2.

The inequality can be proven by consideringwhere T = (X − μ)/σ. This is the expectation of a square, so it is non-negative for all a; however it is also a quadratic polynomial in a. Its discriminant must be non-positive, which gives the required relationship.

Higher moments

High-order moments are moments beyond 4th-order moments.

As with variance, skewness, and kurtosis, these are higher-order statistics, involving non-linear combinations of the data, and can be used for description or estimation of further shape parameters. The higher the moment, the harder it is to estimate, in the sense that larger samples are required in order to obtain estimates of similar quality. This is due to the excess degrees of freedom consumed by the higher orders. Further, they can be subtle to interpret, often being most easily understood in terms of lower order moments – compare the higher-order derivatives of jerk and jounce in physics. For example, just as the 4th-order moment (kurtosis) can be interpreted as "relative importance of tails as compared to shoulders in contribution to dispersion" (for a given amount of dispersion, higher kurtosis corresponds to thicker tails, while lower kurtosis corresponds to broader shoulders), the 5th-order moment can be interpreted as measuring "relative importance of tails as compared to center (mode and shoulders) in contribution to skewness" (for a given amount of skewness, higher 5th moment corresponds to higher skewness in the tail portions and little skewness of mode, while lower 5th moment corresponds to more skewness in shoulders).

Mixed moments

Mixed moments are moments involving multiple variables.

The value is called the moment of order (moments are also defined for non-integral ). The moments of the joint distribution of random variables are defined similarly. For any integers , the mathematical expectation is called a mixed moment of order (where ), and is called a central mixed moment of order . The mixed moment is called the covariance and is one of the basic characteristics of dependency between random variables.

Some examples are covariance, coskewness and cokurtosis. While there is a unique covariance, there are multiple co-skewnesses and co-kurtoses.