Related Research Articles

Indro Alessandro Raffaello Schizogene MontanelliKnight Grand Cross OMRI was an Italian journalist, historian, and writer. He was one of the fifty World Press Freedom Heroes according to the International Press Institute.

il Giornale is an Italian language daily newspaper published in Milan, Italy.

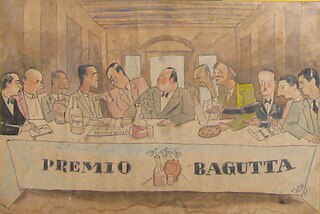

The Bagutta Prize is an Italian literary prize that is awarded annually to Italian writers. The prize originated among patrons of Milan's Bagutta Ristorante. The writer Riccardo Bacchelli discovered the restaurant and soon he regularly gathered numerous friends who would dine there together and discuss books. They began charging fines to the person who arrived last to an appointed meal, or who failed to appear.

Pietro Valpreda was an Italian anarchist, poet, dancer and novelist.

The Years of Lead is a term used for a period of social and political turmoil in Italy that lasted from the late 1960s until the late 1980s, marked by a wave of both far-left and far-right incidents of political terrorism.

This is a timeline of Italian history, comprising important legal and territorial changes and political events in Italy and its predecessor states, including Ancient Rome and Prehistoric Italy. Date of the prehistoric era are approximate. For further background, see history of Italy and list of Prime Ministers of Italy.

Antonio Annarumma was an Italian policeman, and killed at age 22 while serving during a demonstration called by the Italian (Marxist–Leninist) Communist Party and from the Student Movement. He is considered to be the first victim of the Years of Lead, a period of social and political upheaval in Italy.

Luciano del Castillo is an Italian photographer and journalist specializing in war photography.

The Guerin Sportivo is an Italian sports magazine. It is the oldest sport magazine in the world.

The Acqui Award of History is an Italian prize. The prize was founded in 1968 for remembering the victims of the Acqui Military Division who died in Cefalonia fighting against the Nazis. The jury is composed of seven members: six full professors of history and a group of sixty (60) ordinary readers who have just one representative in the jury. The Acqui Award Prize is divided into three sections: history, popular history, and historical novels. A special prize entitled “Witness to the Times,” given to individual personalities known for their cultural contributions and who have distinguished themselves in describing historical events and contemporary society, may also be conferred. Beginning in 2003 special recognition for work in multimedia and iconography--”History through Images”—was instituted.

The kidnapping of Aldo Moro, also referred to in Italy as Moro Case, was a seminal event in Italian political history.

Sansepolcrismo is a term used to refer to the movement led by Benito Mussolini that preceded Fascism. The Sansepolcrismo takes its name from the rally organized by Mussolini at Piazza San Sepolcro in Milan on March 23, 1919, where he proclaimed the principles of Fasci Italiani di Combattimento, and then published them in the newspaper he co-founded, Il Popolo d'Italia, on June 6, 1919.

Sergio Romano is an Italian writer, journalist, and historian. He is a columnist for the newspaper Corriere della Sera. Romano is also a former Italian ambassador to Moscow.

Inge Feltrinelli was a German-born Italian photographer and director, who with her son Carlo ran the Italian publishing house Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore.

The Italian presidential election of 1971 was held in Italy on 9–24 December 1971.

Mario Cervi was an Italian essayist and journalist.

Leopoldo Longanesi was an Italian journalist, publicist, screenplayer, playwright, writer, and publisher. Longanesi is mostly known in his country for his satirical works on Italian society and people. He also founded the eponymous publishing house in Milan in 1946 and was a mentor-like figure for Indro Montanelli: journalist, historian, and founder of Il Giornale, one of Italy's biggest newspapers.

The expression Years of Mud is used to identify a period of Italian history that coincides roughly with the 1980s.

Roberto Gervaso was an Italian writer and journalist. He won the Premio Bancarella twice: for L'Italia dei Comuni in 1967, and for Cagliostro in 1973.

In Italy, after the war, many armed, paramilitary, far-right organizations were active, as well as far-left ones.

References

- ↑ Book's preface

- ↑ "Anni di piombo: restano le cicatrici" (in Italian). La Stampa. January 4, 1992. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ↑ "quegli anni di piombo e di camaleonti" (in Italian). Corriere della Sera. January 17, 1992. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ↑ "MONTANELLI Addio Italia, patria perduta" (in Italian). Corriere della Sera. November 23, 1997. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)