The philosophy of perception is concerned with the nature of perceptual experience and the status of perceptual data, in particular how they relate to beliefs about, or knowledge of, the world. Any explicit account of perception requires a commitment to one of a variety of ontological or metaphysical views. Philosophers distinguish internalist accounts, which assume that perceptions of objects, and knowledge or beliefs about them, are aspects of an individual's mind, and externalist accounts, which state that they constitute real aspects of the world external to the individual. The position of naïve realism—the 'everyday' impression of physical objects constituting what is perceived—is to some extent contradicted by the occurrence of perceptual illusions and hallucinations and the relativity of perceptual experience as well as certain insights in science. Realist conceptions include phenomenalism and direct and indirect realism. Anti-realist conceptions include idealism and skepticism. Recent philosophical work have expanded on the philosophical features of perception by going beyond the single paradigm of vision.

Perception is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system, which in turn result from physical or chemical stimulation of the sensory system. Vision involves light striking the retina of the eye; smell is mediated by odor molecules; and hearing involves pressure waves.

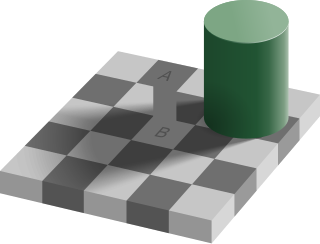

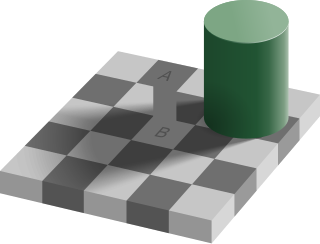

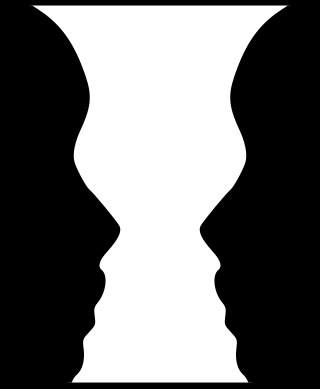

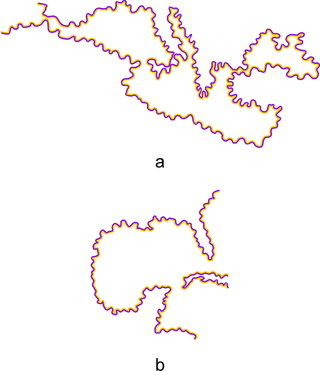

In visual perception, an optical illusion is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide variety; their categorization is difficult because the underlying cause is often not clear but a classification proposed by Richard Gregory is useful as an orientation. According to that, there are three main classes: physical, physiological, and cognitive illusions, and in each class there are four kinds: Ambiguities, distortions, paradoxes, and fictions. A classical example for a physical distortion would be the apparent bending of a stick half immerged in water; an example for a physiological paradox is the motion aftereffect. An example for a physiological fiction is an afterimage. Three typical cognitive distortions are the Ponzo, Poggendorff, and Müller-Lyer illusion. Physical illusions are caused by the physical environment, e.g. by the optical properties of water. Physiological illusions arise in the eye or the visual pathway, e.g. from the effects of excessive stimulation of a specific receptor type. Cognitive visual illusions are the result of unconscious inferences and are perhaps those most widely known.

Gestalt psychology, gestaltism, or configurationism is a school of psychology and a theory of perception that emphasises the processing of entire patterns and configurations, and not merely individual components. It emerged in the early twentieth century in Austria and Germany as a rejection of basic principles of Wilhelm Wundt's and Edward Titchener's elementalist and structuralist psychology.

The term phi phenomenon is used in a narrow sense for an apparent motion that is observed if two nearby optical stimuli are presented in alternation with a relatively high frequency. In contrast to beta movement, seen at lower frequencies, the stimuli themselves do not appear to move. Instead, a diffuse, amorphous shadowlike something seems to jump in front of the stimuli and occlude them temporarily. This shadow seems to have nearly the color of the background. Max Wertheimer first described this form of apparent movement in his habilitation thesis, published 1912, marking the birth of Gestalt psychology.

The consciousness and binding problem is the problem of how objects, background and abstract or emotional features are combined into a single experience.

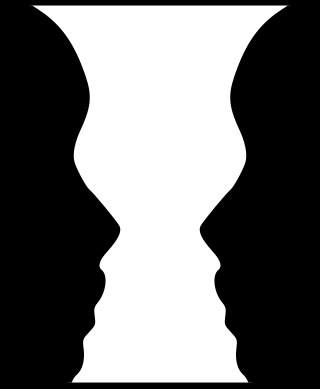

Figure–ground organization is a type of perceptual grouping that is a vital necessity for recognizing objects through vision. In Gestalt psychology it is known as identifying a figure from the background. For example, black words on a printed paper are seen as the "figure", and the white sheet as the "background".

Holonomic brain theory is a branch of neuroscience investigating the idea that human consciousness is formed by quantum effects in or between brain cells. Holonomic refers to representations in a Hilbert phase space defined by both spectral and space-time coordinates. Holonomic brain theory is opposed by traditional neuroscience, which investigates the brain's behavior by looking at patterns of neurons and the surrounding chemistry.

Amodal perception is the perception of the whole of a physical structure when only parts of it affect the sensory receptors. For example, a table will be perceived as a complete volumetric structure even if only part of it—the facing surface—projects to the retina; it is perceived as possessing internal volume and hidden rear surfaces despite the fact that only the near surfaces are exposed to view. Similarly, the world around us is perceived as a surrounding plenum, even though only part of it is in view at any time. Another much quoted example is that of the "dog behind a picket fence" in which a long narrow object is partially occluded by fence-posts in front of it, but is nevertheless perceived as a single continuous object. Albert Bregman noted an auditory analogue of this phenomenon: when a melody is interrupted by bursts of white noise, it is nonetheless heard as a single melody continuing "behind" the bursts of noise.

The Ehrenstein illusion is an optical illusion of brightness or colour perception. The visual phenomena was studied by the German psychologist Walter H. Ehrenstein (1899–1961) who originally wanted to modify the theory behind the Hermann grid illusion. In the discovery of the optical illusion, Ehrenstein found that grating patterns of straight lines that stop at a certain point appear to have a brighter centre, compared to the background.

Visual perception is the ability to interpret the surrounding environment through photopic vision, color vision, scotopic vision, and mesopic vision, using light in the visible spectrum reflected by objects in the environment. This is different from visual acuity, which refers to how clearly a person sees. A person can have problems with visual perceptual processing even if they have 20/20 vision.

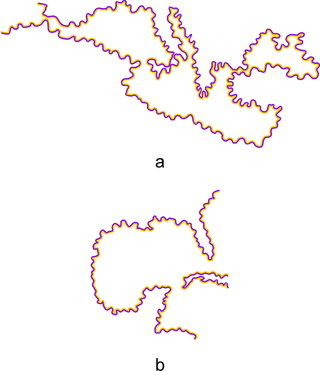

Scene statistics is a discipline within the field of perception. It is concerned with the statistical regularities related to scenes. It is based on the premise that a perceptual system is designed to interpret scenes.

The principles of grouping are a set of principles in psychology, first proposed by Gestalt psychologists to account for the observation that humans naturally perceive objects as organized patterns and objects, a principle known as Prägnanz. Gestalt psychologists argued that these principles exist because the mind has an innate disposition to perceive patterns in the stimulus based on certain rules. These principles are organized into five categories: Proximity, Similarity, Continuity, Closure, and Connectedness.

The watercolor illusion, also referred to as the water-color effect, is an optical illusion in which a white area takes on a pale tint of a thin, bright, intensely colored polygon surrounding it if the coloured polygon is itself surrounded by a thin, darker border. The inner and outer borders of watercolor illusion objects often are of complementary colours. The watercolor illusion is best when the inner and outer contours have chromaticities in opposite directions in color space. The most common complementary pair is orange and purple. The watercolor illusion is dependent on the combination of luminance and color contrast of the contour lines in order to have the color spreading effect occur.

Rainer Mausfeld is a retired German professor of psychology at Kiel University. He did research on the psychology of perception, cognitive science, and the history of psychology. Since 2015, he has published on manipulation in media and politics and the transformation of representative democracy to neoliberal elite democracy.

Amodal completion is the ability to see an entire object despite parts of it being covered by another object in front of it. It is one of the many functions of the visual system which aid in both seeing and understanding objects encountered on an everyday basis. This mechanism allows the world to be perceived as though it is made of coherent wholes. For example, when the sun sets over the horizon it is still perceived as a full circle, despite occlusion causing it to appear as a semi-circle. Another example of this is a cat behind a picket fence. Amodal completion allows the cats to be seen as a full animal continuing behind each picket of the fence. Essentially amodal completion allows for sensory stimulation from any parts of an occluded object we can not directly see.

Kurt Koffka was a German psychologist and professor. He was born and educated in Berlin, Germany; he died in Northampton, Massachusetts, from coronary thrombosis. He was influenced by his maternal uncle, a biologist, to pursue science. He had many interests including visual perception, brain damage, sound localization, developmental psychology, and experimental psychology. He worked alongside Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler to develop Gestalt psychology. Koffka had several publications including "The Growth of the Mind: An Introduction to Child Psychology" (1924) and "The Principles of Gestalt Psychology" (1935) which elaborated on his research.

Ensemble coding, also known as ensemble perception or summary representation, is a theory in cognitive neuroscience about the internal representation of groups of objects in the human mind. Ensemble coding proposes that such information is recorded via summary statistics, particularly the average or variance. Experimental evidence tends to support the theory for low-level visual information, such as shapes and sizes, as well as some high-level features such as face gender. Nonetheless, it remains unclear the extent to which ensemble coding applies to high-level or non-visual stimuli, and the theory remains the subject of active research.

Michael Kubovy is an Israeli American psychologist known for his work on the psychology of perception and psychology of art.

Johan Wagemans is a Belgian experimental psychologist. He is a full professor at the KU Leuven in Leuven (Belgium). He directs a long-term Methusalem project that focuses upon the psychology and neuroscience of visual perception and most recently art perception.