Breton is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language group spoken in Brittany, part of modern-day France. It is the only Celtic language still widely in use on the European mainland, albeit as a member of the insular branch instead of the continental grouping.

Occitan, also known as lenga d'òc by its native speakers, and sometimes also referred to as Provençal, is a Romance language spoken in Southern France, Monaco, Italy's Occitan Valleys, as well as Spain's Val d'Aran in Catalonia; collectively, these regions are sometimes referred to as Occitania. It is also spoken in Calabria in a linguistic enclave of Cosenza area. Some include Catalan in Occitan, as the distance between this language and some Occitan dialects is similar to the distance between different Occitan dialects. Catalan was considered a dialect of Occitan until the end of the 19th century and still today remains its closest relative.

Kornigou are cakes baked in the shape of antlers to commemorate the god of winter shedding his "cuckold" horns as he returns to his kingdom in the Otherworld. This tradition is typically upheld in Celtic households in Brittany and is enacted during Samhain (Halloween). It is a distinctly Pagan tradition which continues to this day.

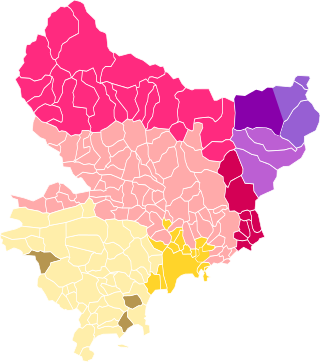

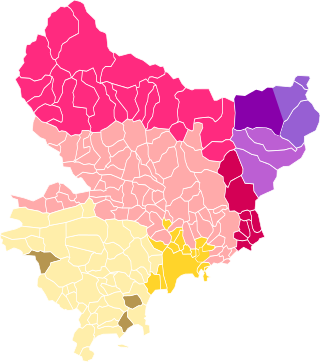

Occitania is the historical region in Western and Southern Europe where the Occitan language was historically spoken and where it is occasionally used as a second language. This cultural area roughly encompasses much of the southern third of France as well as part of Spain, Monaco, and parts of Italy.

France has one official language, the French language. The French government does not regulate the choice of language in publications by individuals, but the use of French is required by law in commercial and workplace communications. In addition to mandating the use of French in the territory of the Republic, the French government tries to promote French in the European Union and globally through institutions such as La Francophonie. The perceived threat from Anglicisation has prompted efforts to safeguard the position of the French language in France.

Niçard, nissart/Niçart, niçois, or nizzardo is the dialect that was historically spoken in the city of Nice, in France, and in a few surrounding communes. Niçard is a subdialect of Provençal, itself a dialect of Occitan. Some Italian irredentists have claimed it as a Ligurian dialect, on false grounds.

The Occitano-Romance or Gallo-Narbonnese, or rarely East Iberian, is a branch of the Romance language group that encompasses the Catalan/Valencian and Occitan languages spoken in parts of southern France and northeastern Spain.

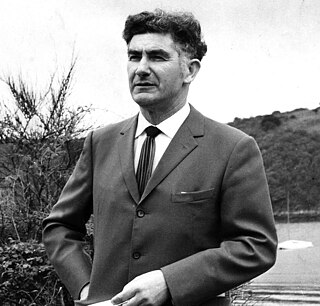

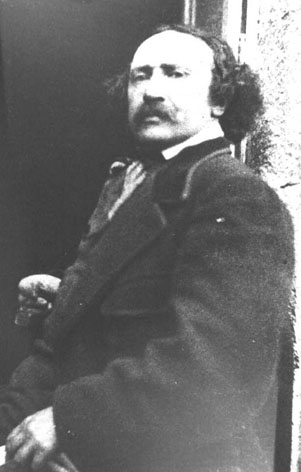

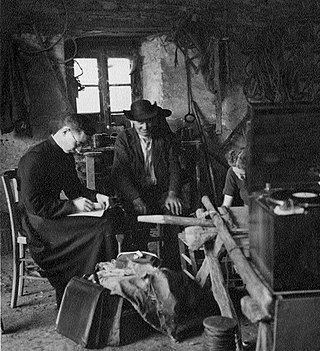

François-Marie Luzel, often known by his Breton name Fañch an Uhel, was a French folklorist and Breton-language poet.

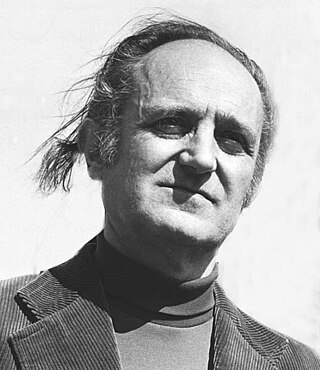

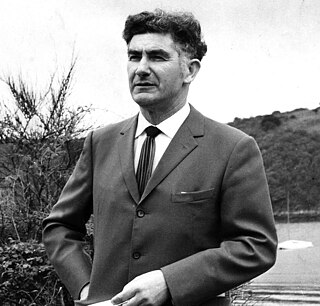

Robèrt Lafont was a French intellectual from Provence. He was a linguist, an author, an historian, an expert in literature and a political theoretician. His name in French reads Robert Lafont.

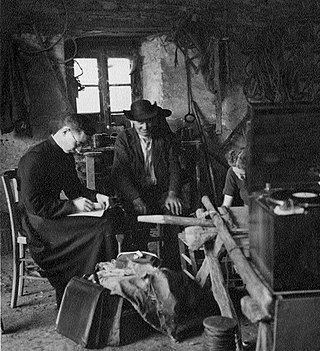

In Occitan, vergonha refers to the effects of various language discriminatory policies of the government of France on its minorities whose native language was deemed a patois, where a Romance language spoken in the country other than Standard French, such as Occitan or the langues d'oïl, as well as other non-Romance languages such as Alsatian and Basque, were suppressed. Vergonha is imagined as a process of "being made to reject and feel ashamed of one's mother tongue through official exclusion, humiliation at school and rejection from the media", as organized and sanctioned by French political leaders from Henri Grégoire onward.

The Croissant is a linguistic transitional zone between the Langue d'oc dialects and the Langue d'oïl dialects, situated in the centre of France where Occitan dialects are spoken that have transitional traits toward French. The name derives from the contours of the zone that resemble a croissant, or crescent.

François Falcʼhun was a French linguist known for his theories about the origin of the Breton language. He was also an ordained Canon in the Catholic clergy.

Fañch Broudig or François Broudic is a Breton journalist and Breton- and French-language writer.

Occitan nationalism is a social and political movement in Occitania. Nationalists seek self-determination, greater autonomy or the creation of a sovereign state of Occitania. The basis of nationalism is linguistic and cultural although currently the Occitan varieties are minority languages within the language area.

Occitania is the southernmost administrative region of metropolitan France excluding Corsica, created on 1 January 2016 from the former regions of Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrénées. The Council of State approved Occitania as the new name of the region on 28 September 2016, coming into effect on 30 September 2016.

The Bourbonnais dialects are spoken in the historic region of Bourbonnais, located in central France and including the department of Allier the area surrounding Saint-Amand-Montrond, in southeastern Cher. This linguistic zone is located between those home to the languages of Oïl, Occitan, and Franco-Provençal.

Paul Sérant is the pen name of Paul Salleron, a French journalist and writer. He was the brother of the Catholic theoretician Louis Salleron. He was a great lover of the French language, but was also a lover of regional diversity, and supported preservation of local cultures such as Breton, Occitan and Basque. His vision for Europe was one in which the nation-states would be dissolved, leaving a federation of ethnic groups.

Jean-Yves Veillard was a French historian.

Charles Le Gall, known as Charlez ar Gall, was a Breton radio broadcaster, activist, and writer. After a career in radio, he worked as a broadcaster for the ORTF's Breton-language programming until his resignation in 1974, and along with his wife Chanig ar Gall, was a pioneer in Breton-language broadcasting.