Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer.

Dmitri Shostakovich's String Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110, was written in three days.

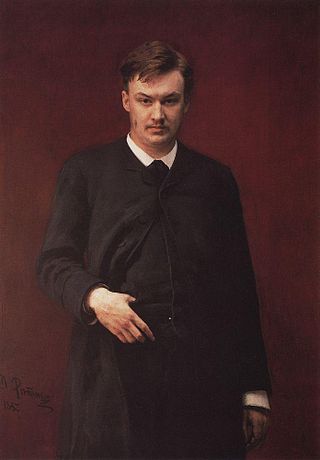

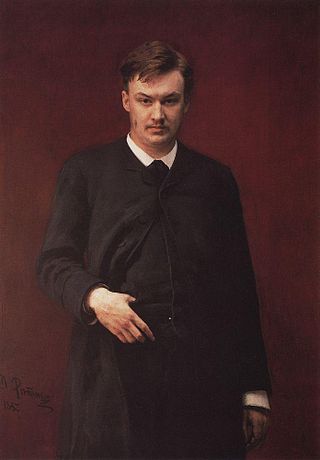

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 and 1928 and was instrumental in the reorganization of the institute into the Petrograd Conservatory, then the Leningrad Conservatory, following the Bolshevik Revolution. He continued as head of the Conservatory until 1930, though he had left the Soviet Union in 1928 and did not return. The best-known student under his tenure during the early Soviet years was Dmitri Shostakovich.

Dmitri Shostakovich's Symphony No. 7 in C major, Op. 60, nicknamed the Leningrad, was begun in Leningrad, completed in the city of Samara in December 1941, and premiered in that city on March 5, 1942. At first dedicated to Lenin, it was eventually submitted in honor of the besieged city of Leningrad, where it was first played under dire circumstances on August 9, 1942, nearly a year into the siege by German forces.

Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his Symphony No. 2 in B major, Op. 14, subtitled To October, for the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. It was first performed by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra and the Academy Capella Choir under Nikolai Malko, on 5 November 1927. After the premiere, Shostakovich made some revisions to the score, and this final version was first played in Moscow later in 1927 under the baton of Konstantin Saradzhev. It was also the first time any version of the work had been played in Moscow.

Dmitri Shostakovich composed his Symphony No. 4 in C minor, Op. 43, between September 1935 and May 1936, after abandoning some preliminary sketch material. In January 1936, halfway through this period, Pravda—under direct orders from Joseph Stalin—published an editorial "Muddle Instead of Music" that denounced the composer and targeted his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. Despite this attack and the political climate of the time, Shostakovich completed the symphony and planned its premiere for December 1936 in Leningrad. After rehearsals began, the orchestra's management cancelled the performance, offering a statement that Shostakovich had withdrawn the work. He may have agreed to withdraw it to relieve orchestra officials of responsibility. The symphony was premiered on 30 December 1961 by the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra led by Kirill Kondrashin.

The Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47, by Dmitri Shostakovich is a work for orchestra composed between April and July 1937. Its first performance was on November 21, 1937, in Leningrad by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky. The premiere was a "triumphal success" that appealed to both the public and official critics, receiving an ovation that lasted well over half an hour.

The Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 54 by Dmitri Shostakovich was written in 1939, and first performed in Leningrad on November 5, 1939 by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky.

The Symphony No. 11 in G minor, Op. 103, by Dmitri Shostakovich was written in 1957 and premiered by the USSR Symphony Orchestra under Natan Rakhlin on 30 October 1957. The subtitle of the symphony refers to the events of the Russian Revolution of 1905, which the symphony depicts. The first performance given outside the Soviet Union took place in London's Royal Festival Hall on 22 January 1958 when Sir Malcolm Sargent conducted the BBC Symphony Orchestra. The United States premiere was performed by Leopold Stokowski conducting the Houston Symphony on 7 April 1958. The symphony was conceived as a popular piece and proved an instant success in Russia, his greatest one since the Leningrad Symphony fifteen years earlier. The work's popular success, as well as its earning him a Lenin Prize in April 1958, marked the composer's formal rehabilitation from the Zhdanov Doctrine of 1948.

The Symphony No. 9 in E-flat major, Op. 70, was composed by Dmitri Shostakovich in 1945. It was premiered on 3 November 1945 in Leningrad by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky.

The Symphony No. 13 in B-flat minor, Op. 113 for bass soloist, bass chorus, and large orchestra was composed by Dmitri Shostakovich in 1962. It consists of five movements, each a setting of a Yevgeny Yevtushenko poem that describes aspects of Soviet history and life. Although the symphony is commonly referred to by the nickname Babi Yar, no such subtitle is designated in Shostakovich's manuscript score.

The Symphony No. 14 in G minor, Op. 135, by Dmitri Shostakovich was completed in the spring of 1969, and was premiered later that year. It is a work for soprano, bass and a small string orchestra with percussion, consisting of eleven linked settings of poems by four authors. Most of the poems deal with the theme of death, particularly that of unjust or early death. They were set in Russian, although two other versions of the work exist with the texts all back-translated from Russian either into their original languages or into German. The symphony is dedicated to Benjamin Britten.

The Symphony No. 15 in A major, Op. 141, composed between late 1970 and July 29, 1971, is the final symphony by Dmitri Shostakovich. It was his first purely instrumental and non-programmatic symphony since the Tenth from 1953. Shostakovich began to plan and sketch the Fifteenth in late 1970, with the intention of composing for himself a cheerful work to mark his 65th birthday the next year. After completing the sketch score in April 1971, he wrote the orchestral score in June while receiving medical treatment in the town of Kurgan. The symphony was completed the following month at his summer dacha in Repino. This was followed by a prolonged period of creative inactivity which did not end until the composition of the Fourteenth Quartet in 1973.

Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his Cello Concerto No. 2, Op. 126, in 1966 in the Crimea. Like the first concerto, it was written for Mstislav Rostropovich, who gave the premiere in Moscow under Yevgeny Svetlanov on 25 September 1966 at the composer's 60th birthday concert. The concerto is sometimes listed as in the key of G, but the score gives no such indication.

The Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77, was originally composed by Dmitri Shostakovich in 1947–48. He was still working on the piece at the time of the Zhdanov Doctrine, and it could not be performed in the period following the composer's denunciation. In the time between the work's initial completion and the first performance, the composer, sometimes with the collaboration of its dedicatee, David Oistrakh, worked on several revisions. The concerto was finally premiered by the Leningrad Philharmonic under Yevgeny Mravinsky on 29 October 1955. It was well-received, Oistrakh remarking on the "depth of its artistic content" and describing the violin part as a "pithy 'Shakespearian' role."

Antiformalist Rayok, also known as Learner's Manual, without opus number, is a satirical cantata for four voices, chorus, and piano by Dmitri Shostakovich. It is subtitled As an aid to students: the struggle of the realistic and formalistic directions in music. It satirizes the conferences that resulted from the Zhdanov decree of 1948 and the anti-formalism campaign in Soviet arts which followed it.

The Symphony No. 6 in E-flat minor, Op. 111, by Sergei Prokofiev was completed and premiered in 1947. Sketches for the symphony exist as early as from June 1945; Prokofiev had reportedly begun work on it prior to composing his Fifth Symphony. He later remarked that the Sixth memorialized the victims of the Great Patriotic War.

A choral symphony is a musical composition for orchestra, choir, and sometimes solo vocalists that, in its internal workings and overall musical architecture, adheres broadly to symphonic musical form. The term "choral symphony" in this context was coined by Hector Berlioz when he described his Roméo et Juliette as such in his five-paragraph introduction to that work. The direct antecedent for the choral symphony is Ludwig van Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. Beethoven's Ninth incorporates part of the Ode an die Freude, a poem by Friedrich Schiller, with text sung by soloists and chorus in the last movement. It is the first example of a major composer's use of the human voice on the same level as instruments in a symphony.

"Muddle Instead of Music: On the Opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District" is an editorial that appeared in the Soviet newspaper Pravda on 28 January 1936. The unsigned article condemned Dmitri Shostakovich's popular opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District as, among other labels, "formalist", "bourgeois", "coarse" and "vulgar". Immediately after publication rumors began to circulate that Joseph Stalin had written the opinion. While this is unlikely, it is almost certain that Stalin was aware of and agreed with the article. "Muddle Instead of Music" was a turning point in Shostakovich's career. The article has since become a well-known example of Soviet censorship of the arts.

The Execution of Stepan Razin is a cantata composed by Dimitri Shostakovich to a libretto by Yevgeny Yevtushenko in 1964. The subject is the execution of Stepan Razin, a Cossack leader who headed a major uprising (1670–71) against the nobility and tsarist bureaucracy in southern Russia.