A mold or mould is one of the structures that certain fungi can form. The dust-like, colored appearance of molds is due to the formation of spores containing fungal secondary metabolites. The spores are the dispersal units of the fungi. Not all fungi form molds. Some fungi form mushrooms; others grow as single cells and are called microfungi.

Fusarium oxysporum, an ascomycete fungus, comprises all the species, varieties and forms recognized by Wollenweber and Reinking within an infrageneric grouping called section Elegans. It is part of the family Nectriaceae.

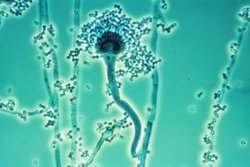

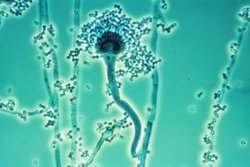

Aspergillus fumigatus is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus, and is one of the most common Aspergillus species to cause disease in individuals with an immunodeficiency.

A conidium, sometimes termed an asexual chlamydospore or chlamydoconidium, is an asexual, non-motile spore of a fungus. The word conidium comes from the Ancient Greek word for dust, κόνις (kónis). They are also called mitospores due to the way they are generated through the cellular process of mitosis. They are produced exogenously. The two new haploid cells are genetically identical to the haploid parent, and can develop into new organisms if conditions are favorable, and serve in biological dispersal.

Mycoremediation is a form of bioremediation in which fungi-based remediation methods are used to decontaminate the environment. Fungi have been proven to be a cheap, effective and environmentally sound way for removing a wide array of contaminants from damaged environments or wastewater. These contaminants include heavy metals, organic pollutants, textile dyes, leather tanning chemicals and wastewater, petroleum fuels, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, pharmaceuticals and personal care products, pesticides and herbicides in land, fresh water, and marine environments.

Microbial corrosion, also called microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC), microbially induced corrosion (MIC), or biocorrosion, is when microbes affect the electrochemical environment of the surface they are on. This usually involves building a biofilm, which can lead to either an increase in corrosion of the surface or, in a process called microbial corrosion inhibition, protect the surface from corrosion.

Gliotoxin is a sulfur-containing mycotoxin that belongs to a class of naturally occurring 2,5-diketopiperazines produced by several species of fungi, especially those of marine origin. It is the most prominent member of the epipolythiopiperazines, a large class of natural products featuring a diketopiperazine with di- or polysulfide linkage. These highly bioactive compounds have been the subject of numerous studies aimed at new therapeutics. Gliotoxin was originally isolated from Gliocladium fimbriatum, and was named accordingly. It is an epipolythiodioxopiperazine metabolite that is one of the most abundantly produced metabolites in human invasive Aspergillosis (IA).

Mycotoxicology is the branch of mycology that focuses on analyzing and studying the toxins produced by fungi, known as mycotoxins. In the food industry it is important to adopt measures that keep mycotoxin levels as low as practicable, especially those that are heat-stable. These chemical compounds are the result of secondary metabolism initiated in response to specific developmental or environmental signals. This includes biological stress from the environment, such as lower nutrients or competition for those available. Under this secondary path the fungus produces a wide array of compounds in order to gain some level of advantage, such as incrementing the efficiency of metabolic processes to gain more energy from less food, or attacking other microorganisms and being able to use their remains as a food source.

Fusarium solani is a species complex of at least 26 closely related filamentous fungi in the division Ascomycota, family Nectriaceae. It is the anamorph of Nectria haematococca. It is a common soil inhabiting mold. Fusarium solani is implicated in plant diseases as well as in serious human diseases such as fungal keratitis.

A fungus is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one of the traditional eukaryotic kingdoms, along with Animalia, Plantae and either Protista or Protozoa and Chromista.

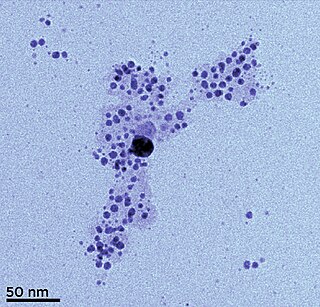

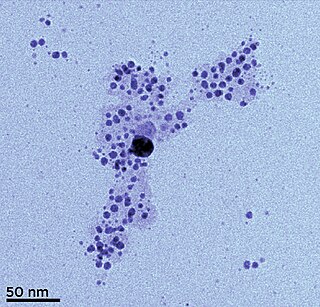

Silver nanoparticles are nanoparticles of silver of between 1 nm and 100 nm in size. While frequently described as being 'silver' some are composed of a large percentage of silver oxide due to their large ratio of surface to bulk silver atoms. Numerous shapes of nanoparticles can be constructed depending on the application at hand. Commonly used silver nanoparticles are spherical, but diamond, octagonal, and thin sheets are also common.

Marine fungi are species of fungi that live in marine or estuarine environments. They are not a taxonomic group, but share a common habitat. Obligate marine fungi grow exclusively in the marine habitat while wholly or sporadically submerged in sea water. Facultative marine fungi normally occupy terrestrial or freshwater habitats, but are capable of living or even sporulating in a marine habitat. About 444 species of marine fungi have been described, including seven genera and ten species of basidiomycetes, and 177 genera and 360 species of ascomycetes. The remainder of the marine fungi are chytrids and mitosporic or asexual fungi. Many species of marine fungi are known only from spores and it is likely a large number of species have yet to be discovered. In fact, it is thought that less than 1% of all marine fungal species have been described, due to difficulty in targeting marine fungal DNA and difficulties that arise in attempting to grow cultures of marine fungi. It is impracticable to culture many of these fungi, but their nature can be investigated by examining seawater samples and undertaking rDNA analysis of the fungal material found.

The mycorrhizosphere is the region around a mycorrhizal fungus in which nutrients released from the fungus increase the microbial population and its activities. The roots of most terrestrial plants, including most crop plants and almost all woody plants, are colonized by mycorrhiza-forming symbiotic fungi. In this relationship, the plant roots are infected by a fungus, but the rest of the fungal mycelium continues to grow through the soil, digesting and absorbing nutrients and water and sharing these with its plant host. The fungus in turn benefits by receiving photosynthetic sugars from its host. The mycorrhizosphere consists of roots, hyphae of the directly connected mycorrhizal fungi, associated microorganisms, and the soil in their direct influence.

Myceliophthora thermophila is an ascomycete fungus that grows optimally at 45–50 °C (113–122 °F). It efficiently degrades cellulose and is of interest in the production of biofuels. The genome has recently been sequenced, revealing the full range of enzymes used by this organism for the degradation of plant cell wall material.

Aspergillus clavatus is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus with conidia dimensions 3–4.5 x 2.5–4.5 μm. It is found in soil and animal manure. The fungus was first described scientifically in 1834 by the French mycologist John Baptiste Henri Joseph Desmazières.

Plant–fungus horizontal gene transfer is the movement of genetic material between individuals in the plant and fungus kingdoms. Horizontal gene transfer is universal in fungi, viruses, bacteria, and other eukaryotes. Horizontal gene transfer research often focuses on prokaryotes because of the abundant sequence data from diverse lineages, and because it is assumed not to play a significant role in eukaryotes.

Cladosporium oxysporum is an airborne fungus that is commonly found outdoors and is distributed throughout the tropical and subtropical region, it is mostly located In Asia and Africa. It spreads through airborne spores and is often extremely abundant in outdoor air during the spring and summer seasons. It mainly feeds on decomposing organic matter in warmer climates, but can also be parasitic and feed on living plants. The airborne spores can occasionally cause cutaneous infections in humans, and the high prevalence of C. oxysporum in outdoor air during warm seasons contributes to its importance as an etiological agent of allergic disease and possibly human cutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in tropical regions.

Aspergillus giganteus is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus that grows as a mold. It was first described in 1901 by Wehmer, and is one of six Aspergillus species from the Clavati section of the subgenus Fumigati. Its closest taxonomic relatives are Aspergillus rhizopodus and Aspergillus longivescia.

Priyabrata Mukherjee is an American, academic researcher and professor. He is a Presbyterian Health Foundation presidential professor at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and associate director for translational research at Stephenson Cancer Center at the OU Health Sciences Center. He also holds the Peggy and Charles Stephenson endowed chair in cancer laboratory research at the OU Health Sciences Center.

Hemibiotrophs are the spectrum of plant pathogens, including bacteria, oomycete and a group of plant pathogenic fungi that keep its host alive while establishing itself within the host tissue, taking up the nutrients with brief biotrophic-like phase. It then, in later stages of infection switches to a necrotrophic life-style, where it rampantly kills the host cells, deriving its nutrients from the dead tissues.