Related Research Articles

Poseidon is one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses. He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cities and colonies. In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, Poseidon was venerated as a chief deity at Pylos and Thebes, with the cult title "earth shaker"; in the myths of isolated Arcadia, he is related to Demeter and Persephone and was venerated as a horse, and as a god of the waters. Poseidon maintained both associations among most Greeks: he was regarded as the tamer or father of horses, who, with a strike of his trident, created springs. His Roman equivalent is Neptune.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Helios is the god who personifies the Sun. His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyperion and Phaethon. Helios is often depicted in art with a radiant crown and driving a horse-drawn chariot through the sky. He was a guardian of oaths and also the god of sight. Though Helios was a relatively minor deity in Classical Greece, his worship grew more prominent in late antiquity thanks to his identification with several major solar divinities of the Roman period, particularly Apollo and Sol. The Roman Emperor Julian made Helios the central divinity of his short-lived revival of traditional Roman religious practices in the 4th century AD.

Alope was in Greek mythology a mortal woman, the daughter of Cercyon, known for her great beauty.

Ageladas or Hagelaedas was a celebrated Greek (Argive) sculptor, who flourished in the latter part of the 6th and the early part of the 5th century BC.

In Greek mythology, Pelops was king of Pisa in the Peloponnesus region. He was the son of Tantalus and the father of Atreus.

Hippodamia was a Greek mythological figure. She was the queen of Pisa and the wife of Pelops, appearing with Pelops at a potential cult site in Ancient Olympia.

In Greek mythology, Myrtilus was a divine hero and son of Hermes. His mother is said variously to be the Amazon Myrto; Phaethusa, daughter of Danaus; or a nymph or mortal woman named Clytie, Clymene or Cleobule (Theobule). Myrtilus was the charioteer of King Oenomaus of Pisa in Elis, on the northwest coast of the Peloponnesus.

In Greek mythology, King Oenomaus of Pisa, was the father of Hippodamia and the son of Ares. His name Oinomaos denotes a wine man.

Neptune is the god of freshwater and the sea in the Roman religion. He is the counterpart of the Greek god Poseidon. In the Greek-inspired tradition, he is a brother of Jupiter and Pluto, with whom he presides over the realms of heaven, the earthly world, and the seas. Salacia is his wife.

Panhellenic Games is the collective term for four separate religious festivals held in ancient Greece that became especially well known for the athletic competitions they included. The four festivals were: the Olympic Games, which were held at Olympia in honor of Zeus; the Pythian Games, which took place in Delphi and honored Apollo; the Nemean Games, occurring at Nemea and also honoring Zeus; and, finally, the Isthmian Games set in Isthmia and held in honor of Poseidon. The places at which these games were held were considered to be "the four great panhellenic sanctuaries." Each of these Games took place in turn every four years, starting with the Olympics. Along with the fame and notoriety of winning the ancient Games, the athletes earned different crowns of leaves from the different Games. From the Olympics, the victor won an olive wreath, from the Pythian Games a laurel wreath, from the Nemean Games a crown of wild celery leaves, and from the Isthmian Games a crown of pine.

Chariot racing was one of the most popular ancient Greek, Roman, and Byzantine sports. In Greece, chariot racing played an essential role in aristocratic funeral games from a very early time. With the institution of formal races and permanent racetracks, chariot racing was adopted by many Greek states and their religious festivals. Horses and chariots were very costly. Their ownership was a preserve of the wealthiest aristocrats, whose reputations and status benefitted from offering such extravagant, exciting displays. Their successes could be further broadcast and celebrated through commissioned odes and other poetry.

The hippocampus, or hippocamp or hippokampos, sometimes called a "sea-horse" in English, is a mythological creature mentioned in Etruscan, Greek, Phoenician, Pictish and Roman mythologies, typically depicted as having the upper body of a horse with the lower body of a fish.

The ancient Olympic Games, or the ancient Olympics, were a series of athletic competitions among representatives of city-states and one of the Panhellenic Games of ancient Greece. They were held at the Panhellenic religious sanctuary of Olympia, in honor of Zeus, and the Greeks gave them a mythological origin. The originating Olympic Games are traditionally dated to 776 BC. The games were held every four years, or Olympiad, which became a unit of time in historical chronologies. These Olympiads were referred to based on the winner of their stadion sprint, e.g., "the third year of the eighteenth Olympiad when Ladas of Argos won the stadion". They continued to be celebrated when Greece came under Roman rule in the 2nd century BC. Their last recorded celebration was in AD 393, under the emperor Theodosius I, but archaeological evidence indicates that some games were still held after this date. The games likely came to an end under Theodosius II, possibly in connection with a fire that burned down the temple of the Olympian Zeus during his reign.

The trigarium was an equestrian training ground in the northwest corner of the Campus Martius in ancient Rome. Its name was taken from the triga, a three-horse chariot.

The di inferi or dii inferi were a shadowy collective of ancient Roman deities associated with death and the underworld. The epithet inferi is also given to the mysterious Manes, a collective of ancestral spirits. The most likely origin of the word Manes is from manus or manis, meaning "good" or "kindly," which was a euphemistic way to speak of the inferi so as to avert their potential to harm or cause fear.

In ancient Roman religion, the October Horse was an animal sacrifice to Mars carried out on October 15, coinciding with the end of the agricultural and military campaigning season. The rite took place during one of three horse-racing festivals held in honor of Mars, the others being the two Equirria on February 27 and March 14.

In the topography of ancient Rome, the Tarentum or Terentum was a religious precinct north of the Trigarium, a field for equestrian exercise, in the Campus Martius. The archaeological survey of the site shows that it had no buildings.

The Greek lyric poet Pindar composed odes to celebrate victories at all four Panhellenic Games. Of his fourteen Olympian Odes, glorifying victors at the Ancient Olympic Games, the First was positioned at the beginning of the collection by Aristophanes of Byzantium since it included praise for the games as well as of Pelops, who first competed at Elis. It was the most quoted in antiquity and was hailed as the "best of all the odes" by Lucian. Pindar composed the epinikion in honour of his then patron Hieron I, tyrant of Syracuse, whose horse Pherenikos and its jockey were victorious in the single horse race in 476 BC.

The Hippodrome of Olympia housed the equestrian contests of the Ancient Olympic Games. According to Pausanias, it was situated to the south of the Stadium and covered a large area four stadia long and one stade four plethora wide. The hippodrome was a wide, flat, open space where the starting point and the finish line were designated with a pole and a second smaller pole called nyssa designated the turning point.

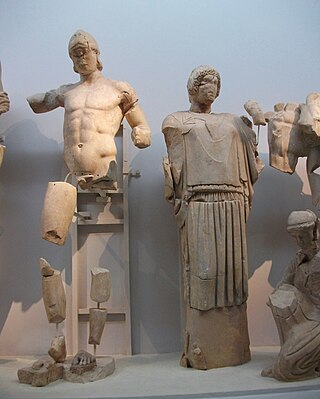

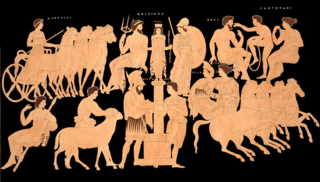

The Eastern pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia depicts the tale of Pelops just before the chariot race wherein he kills the king Oenomaus in order to win the hand of his daughter Hippodamia. The depiction of this chariot race on the east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, along with that of the Twelve Labours of Heracles on the metopes of the frieze, relate to the location of the temple in Olympia; the chariot race and Heracles were both believed to have started the tradition of the Olympic Games.

References

- ↑ Translated into Latin as equorum conturbator by Gerolamo Cardano, De subtilitate (Basil, 1664), Book 7 de lapidibus, p. 282.

- ↑ John H. Humphrey, Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing (University of California Press, 1986), p. 9.

- ↑ Humphrey, Roman Circuses, p. 9.

- ↑ Robert Parker, On Greek Religion (Cornell University Press, 2011), pp. 105–106; Robert Kugelmann, The Windows of Soul: Psychological Physiology of the Human Eye and Primary Glaucoma (Associated University Presses, 1983), pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Robin Hard, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology Based on H. J. Rose's Handbook of Greek Mythology (Routledge, 2004), p. 432; Pausanias (6.20.19) says the Olympian Taraxippos was the most terrifying.

- ↑ Pausanias, Guide to Greece 6.20.15.

- ↑ Humphrey, Roman Circuses, p. 258.

- ↑ Gregory Nagy, Greek Mythology and Poetics (Cornell University Press, 1990), pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Humphrey, Roman Circuses, p. 62.

- ↑ Humphrey, Roman Circuses, pp. 15, 62.

- ↑ Humphrey, Roman Circuses, p. 258; Paul Plass, The Game of Death in Ancient Rome: Arena Sport and Political Suicide (University of Wisconsin Press, 1995), p. 40.

- ↑ Eva D'Ambra, "Racing with Death: Circus Sarcophagi and the Commemoration of Children in Roman Italy" in Constructions of Childhood in Ancient Greece and Italy (American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2007), p. 351.

- ↑ William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology

- ↑ Lycophron, Alexandra 31, note on Ischenus.

- ↑ Pausanias, Guide to Greece 6.20.19.

- ↑ Pausanias, Guide to Greece 6.20.19.

- ↑ Aristophanes, Knights 247; Lowell Edmunds, Cleon, Knights and Aristophanes' Politics (University Press of America, 1987), p. 5.