Guinevere, also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First mentioned in literature in the early 12th century, nearly 700 years after the purported times of Arthur, Guinevere has since been portrayed as everything from a fatally flawed, villainous, and opportunistic traitor to a noble and virtuous lady. The variably told motif of abduction of Guinevere, or of her being rescued from some other peril, features recurrently and prominently in many versions of the legend.

Lancelot du Lac, alternatively written as Launcelot and other variants, is a popular character in Arthurian legend's chivalric romance tradition. He is typically depicted as King Arthur's close companion and one of the greatest Knights of the Round Table, as well as a secret lover of Arthur's wife, Guinevere.

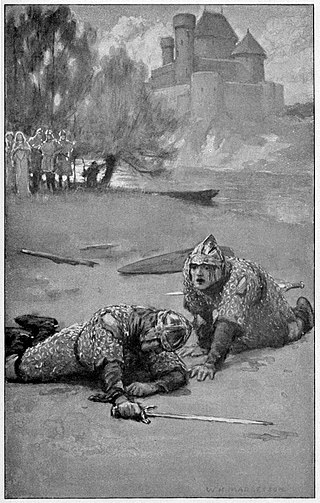

Mordred or Modred is a major figure in the legend of King Arthur. The earliest known mention of a possibly historical Medraut is in the Welsh chronicle Annales Cambriae, wherein he and Arthur are ambiguously associated with the Battle of Camlann in a brief entry for the year 537. Medraut's figure seemed to have been regarded positively in the early Welsh tradition and may have been related to that of Arthur's son. As Modredus, Mordred was depicted as Arthur's traitorous nephew and a legitimate son of King Lot in the pseudo-historical work Historia Regum Britanniae, which then served as the basis for the subsequent evolution of the legend from the 12th century. Later variants most often characterised Mordred as Arthur's villainous bastard son, born of an incestuous relationship with his half-sister, the queen of Lothian or Orkney named either Anna, Orcades, or Morgause. The accounts presented in the Historia and most other versions include Mordred's death at Camlann, typically in a final duel, during which he manages to mortally wound his own slayer, Arthur. Mordred is usually a brother or half-brother to Gawain; however, his other family relations, as well as his relationships with Arthur's wife Guinevere, vary greatly.

Galahad, sometimes referred to as Galeas or Galath, among other versions of his name, is a knight of King Arthur's Round Table and one of the three achievers of the Holy Grail in Arthurian legend. He is the illegitimate son of Sir Lancelot du Lac and Lady Elaine of Corbenic and is renowned for his gallantry and purity as the most perfect of all knights. Emerging quite late in the medieval Arthurian tradition, Sir Galahad first appears in the Lancelot–Grail cycle, and his story is taken up in later works, such as the Post-Vulgate Cycle, and Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur. In Arthurian literature, he replaced Percival as the hero in the quest for the Holy Grail.

The Knights of the Round Table are the legendary knights of the fellowship of King Arthur that first appeared in the Matter of Britain literature in the mid-12th century. The Knights are a chivalric order dedicated to ensuring the peace of Arthur's kingdom following an early warring period, entrusted in later years to undergo a mystical quest for the Holy Grail. The Round Table at which they meet is a symbol of the equality of its members, who range from sovereign royals to minor nobles.

Le Morte d'Arthur is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the Round Table, along with their respective folklore. In order to tell a "complete" story of Arthur from his conception to his death, Malory compiled, rearranged, interpreted and modified material from various French and English sources. Today, this is one of the best-known works of Arthurian literature. Many authors since the 19th-century revival of the legend have used Malory as their principal source.

Gareth is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend. He is the youngest son of King Lot and Queen Morgause, King Arthur's half-sister, thus making him Arthur's nephew, as well as brother to Gawain, Agravain and Gaheris, and either a brother or half-brother of Mordred. Gareth is particularly notable in Le Morte d'Arthur, where one of its eight books is named after and largely dedicated to him, and in which he is also known by his nickname Beaumains.

Maleagant is a villain from Arthurian legend. In a number of versions of a popular episode, Maleagant abducts King Arthur’s wife, Queen Guinevere, necessitating her rescue by Arthur and his knights. The earliest surviving version of this episode names the abductor Melwas; as Maleagant, he debuts as Lancelot's archenemy in Chrétien de Troyes' French romance Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart. However, all surviving versions seem to be later adaptations of a stock narrative of significantly earlier provenance.

Gaheris is a Knight of the Round Table in the chivalric romance tradition of Arthurian legend. A nephew of King Arthur, Gaheris is the third son of Arthur's sister or half-sister Morgause and her husband Lot, King of Orkney and Lothian. He is the younger brother of Gawain and Agravain, the older brother of Gareth, and half-brother of Mordred. His figure may have been originally derived from that of a brother of Gawain in the early Welsh tradition and then later split into a separate character of another brother, today best known as Gareth. German poetry also described him as Gawain's cousin instead of brother.

Agravain is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend, whose first known appearance is in the works of Chrétien de Troyes. He is the second eldest son of King Lot of Orkney with one of King Arthur's sisters known as Anna or Morgause, thus nephew of King Arthur, and brother to Sir Gawain, Gaheris, and Gareth, as well as half-brother to Mordred. Agravain secretly makes attempts on the life of his hated brother Gaheris starting in the Vulgate Cycle, participates in the slayings of Lamorak and Palamedes in the Post-Vulgate Cycle, and murders Dinadan in the Prose Tristan. In the French prose cycle tradition included in Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, together with Mordred, he then plays a leading role by exposing his aunt Guinevere's affair with Lancelot, which leads to his death at Lancelot's hand.

Lamorak is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend. Introduced in the Prose Tristan, Lamorak reappears in later works including the Post-Vulgate Cycle and Thomas Malory's compilation Le Morte d'Arthur. Malory refers to him as Arthur's third best knight, only inferior to Lancelot and Tristan, and the Prose Tristan names his as one of the top five, but Lamorak was not exceptionally popular in the romance tradition, confined to the cyclical material and subordinate to more prominent characters.

Balinthe Savage, also known as the Knight with the Two Swords, is a character in the Arthurian legend. Like Galahad, Balin is a late addition to the medieval Arthurian world. His story, as told by Thomas Malory in Le Morte d'Arthur, is based upon that told in the continuation of the second book of the Post-Vulgate cycle of legend, the Suite du Merlin.

Dinadan is a Cornish Knight of the Round Table in the Arthurian legend's chivalric romance tradition. In the Prose Tristan and its adaptations, Dinadan is a close friend of the protagonist Tristan. Known for his cynical humor and pragmatism, and also for his severe anti-chivalric attitudes in the original French texts, he serves as a foil to Tristan in his softened portrayal in the English compilation Le Morte d'Arthur. In both Malory and his French sources, Dinadan appears in several often comedic episodes until his murder by Mordred and Agravain. Despite his relatively minor role, he has become a major subject of especially Malorian scholarship.

Bagdemagus, also known as Bademagu, Bademagus, Bademaguz, Bagdemagu, Bagomedés, Baldemagu, Baldemagus, Bandemagu, Bandemagus, Bangdemagew, Baudemagu, Baudemagus, and other variants, is a character in the Arthurian legend, usually depicted as king of the land of Gorre and a Knight of the Round Table. He originally figures in literature the father of the knight Maleagant, who abducts King Arthur's wife Queen Guinevere in several versions of a popular episode. Bagdemagus first appears in French sources, but the character may have developed out of the earlier Welsh traditions of Guinevere's abduction, an evolution suggested by the distinctively otherworldly portrayal of his realm. He is portrayed as a kinsman and ally of Arthur and a wise and virtuous king, despite the actions of his son. In later versions, his connection to Maleagant disappears altogether.

King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table is a retelling of the Arthurian legends, principally Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, by Roger Lancelyn Green. It was intended for children. It was first published by Puffin Books in 1953 and has since been reprinted many times. In 2008, it was reissued in the Puffin Classics series with an introduction by David Almond, and the original illustrations by Lotte Reiniger.

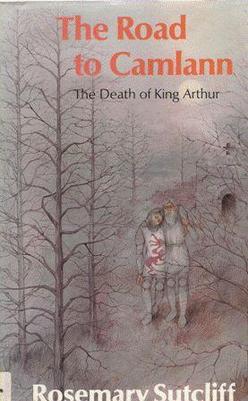

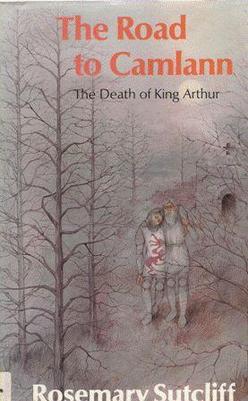

The Road to Camlann: The Death of King Arthur is the third book in Rosemary Sutcliff's Arthurian trilogy, after The Sword and the Circle and The Light Beyond the Forest. This book portrays the events that lead to the Battle of Camlann and the downfall of Camelot, including Guinevere and Lancelot's secret affair, and the betrayal of Arthur's illegitimate son Mordred.

The StanzaicMorte Arthur is an anonymous 14th-century Middle English poem in 3,969 lines, about the adulterous affair between Lancelot and Guinevere, and Lancelot's tragic dissension with King Arthur. The poem is usually called the Stanzaic Morte Arthur or Stanzaic Morte to distinguish it from another Middle English poem, the Alliterative Morte Arthure. It exercised enough influence on Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur to have, in the words of one recent scholar, "played a decisive though largely unacknowledged role in the way succeeding generations have read the Arthurian legend".

The Story of King Arthur and His Knights is a 1903 children's novel by the American illustrator and writer Howard Pyle. The book contains a compilation of various stories, adapted by Pyle, regarding the legendary King Arthur of Britain and select Knights of the Round Table. Pyle's novel begins with Arthur in his youth and continues through numerous tales of bravery, romance, battle, and knighthood.

Guiomar is the best known name of a character appearing in many medieval texts relating to the Arthurian legend, often in relationship with Morgan le Fay or a similar fairy queen type character.