Harold Pinter was a British playwright, screenwriter, director and actor. A Nobel Prize winner, Pinter was one of the most influential modern British dramatists with a writing career that spanned more than 50 years. His best-known plays include The Birthday Party (1957), The Homecoming (1964) and Betrayal (1978), each of which he adapted for the screen. His screenplay adaptations of others' works include The Servant (1963), The Go-Between (1971), The French Lieutenant's Woman (1981), The Trial (1993) and Sleuth (2007). He also directed or acted in radio, stage, television and film productions of his own and others' works.

Sir Alan Arthur Bates was an English actor who came to prominence in the 1960s, when he appeared in films ranging from the popular crime drama Whistle Down the Wind to the "kitchen sink" drama A Kind of Loving.

Howard Barker is a British playwright, screenwriter and writer of radio drama, painter, poet, and essayist, writing predominantly on playwriting and the theatre. The author of an extensive body of dramatic works since the 1970s, he is best known for his plays Scenes from an Execution, Victory, The Castle, The Possibilities, The Europeans, Judith and Gertrude – The Cry as well as being a founding member of, primary playwright for and stage designer for British theatre company The Wrestling School.

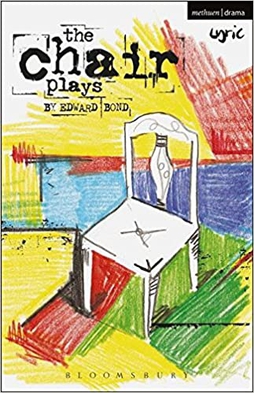

Thomas Edward Bond was an English playwright, theatre director, poet, dramatic theorist and screenwriter. He was the author of some 50 plays, among them Saved (1965), the production of which was instrumental in the abolition of theatre censorship in the UK. His other well-received works include Narrow Road to the Deep North (1968), Lear (1971), The Sea (1973), The Fool (1975), Restoration (1981), and the War trilogy (1985). Bond was broadly considered among the major living dramatists but he has always been and remains highly controversial because of the violence shown in his plays, the radicalism of his statements about modern theatre and society, and his theories on drama.

The Experimental Theatre Club (ETC) is a student dramatic society at the University of Oxford, England. It was founded in 1936 by Nevill Coghill as an alternative company to the Oxford University Dramatic Society (OUDS), and produces several productions a year.

Aikaterini Hadjipateras, known professionally as Kathryn Hunter, is a British–American actress and theatre director, known for her appearances as Arabella Figg in the Harry Potter film series, Eedy Karn in the Disney+ Star Wars spinoff series Andor, as the Three Witches in Joel Coen's The Tragedy of Macbeth, and most recently as Swiney in Yorgos Lanthimos's Poor Things. Hunter was born in New York to Greek parents, and was raised in England. She trained at RADA where she is now an associate, and regularly directs student productions.

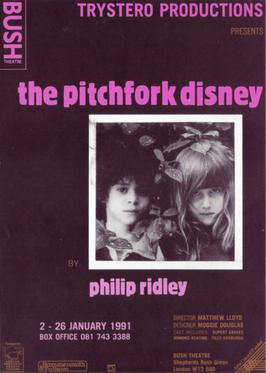

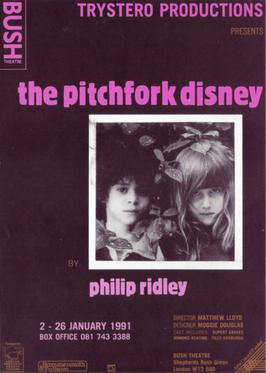

The Pitchfork Disney is a 1991 stage play by Philip Ridley. It was his first professional stage work, having also produced work as a visual artist, novelist, filmmaker, and scriptwriter for film and radio. The play premiered at the Bush Theatre in London, UK in 1991 and was directed by Matthew Lloyd, who directed most of Ridley's subsequent early plays.

Milton Shulman was a Canadian author, film and theatre critic who was based in the United Kingdom from 1943.

Mercury Fur is a play written by Philip Ridley which premiered in 2005. It is Ridley's fifth adult stage play and premiered at the Plymouth Theatre Royal, before moving to the Menier Chocolate Factory in London.

Tom Burke is an English actor. He is best known for his roles as Athos in the 2014–2016 BBC TV series The Musketeers, Dolokhov in the 2016 BBC literary-adaptation miniseries War & Peace, the eponymous character Cormoran Strike in the BBC series Strike, and Orson Welles in the 2020 film Mank.

Denise Gough is an Irish actress. She has received a number of accolades, including two Laurence Olivier Awards as well as a nominations for a Tony Award and a British Academy Television Award.

Blue Heart is two one act plays, written by Caryl Churchill and copyrighted in 1997. The first play, Heart’s Desire, is about a family waiting on the arrival of their daughter Suzy. The second play Blue Kettle, is about a man named Derek who goes around telling women they're his mother because he was adopted at birth. The women believe him and truly find ways to tell him the way he is their son. Blue Heart is highly regarded by critics.

Scenes from an Execution is a play by the English playwright Howard Barker. The plot revolves around a female artist's struggles against the Venetian city-state in the aftermath of the 16th century Battle of Lepanto. Although the city commissions the painting to celebrate the victory over the Turks, the artist's vision differs dramatically from that of the Doge and the Catholic Church. The play has been described as "Barker's most famous and accessible play".

Caryl Lesley Churchill is a British playwright known for dramatising the abuses of power, for her use of non-naturalistic techniques, and for her exploration of sexual politics and feminist themes. Celebrated for works such as Cloud 9 (1979), Top Girls (1982), Serious Money (1987), Blue Heart (1997), Far Away (2000), and A Number (2002), she has been described as "one of Britain's greatest poets and innovators for the contemporary stage". In a 2011 dramatists' poll by The Village Voice, five out of the 20 polled writers listed Churchill as the greatest living playwright.

The Fastest Clock in the Universe is a two act play by Philip Ridley. It was Ridley's second stage play and premiered at the Hampstead Theatre, London on 14 May 1992 and featured Jude Law in his first paid theatre role, playing the part of Foxtrot Darling. The production was the second collaboration between Ridley and director Matthew Lloyd, who would go on to direct the original productions for the majority of Ridley's plays until the year 2001.

Andrew Rissik is a British scriptwriter, journalist and critic best known for the BBC Radio 3 trilogy, Troy and the five-part thriller serial for Radio 4, The Psychedelic Spy. He was theatre critic at The Independent from 1986 to 1988, and a book reviewer for The Guardian from 1999 to 2001. His full-time writing and journalistic career came to an end in early 1988 when he was diagnosed with Myalgic encephalomyelitis (M.E.), from which he still suffers.

Alice Birch is a British playwright and screenwriter. Birch has written several plays, including Revolt. She Said. Revolt Again. for which she was awarded the George Devine Award for Most Promising New Playwright, and Anatomy of a Suicide for which she won the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize. Birch was also the screenwriter for the film Lady Macbeth and has written for such television shows as Succession, Normal People, and Dead Ringers.

Here We Go is a 2015 play by Caryl Churchill. Critics' reviews were generally positive.

Glass. Kill. Bluebeard. Imp. is a 2019 series of plays by British playwright Caryl Churchill that were premiered together.

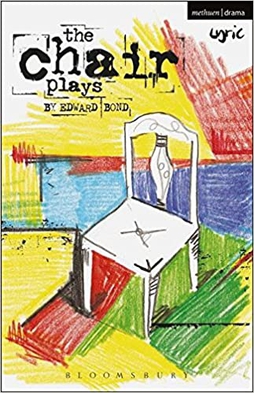

The Chair Plays are a trilogy of plays by English dramatist Edward Bond. The trilogy includes Have I None, The Under Room, and Chair. Have I None was premiered by Big Brum on 2 November 2000 at Birmingham's Castle Vale Artsite. The Under Room was also premiered by Big Brum at MAC in October 2005. Chair was written specially for radio, and while it was written in 2000, its first staged production was in Lisbon, at the Teatro da Cornucópia in June 2005. The London premiere of the entire trilogy was at Lyric Hammersmith, on 19 April 2012. Have I None and Chair received mostly positive reviews, but The Under Room polarized critics.