Related Research Articles

The Federal Reserve System is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of financial panics led to the desire for central control of the monetary system in order to alleviate financial crises. Over the years, events such as the Great Depression in the 1930s and the Great Recession during the 2000s have led to the expansion of the roles and responsibilities of the Federal Reserve System.

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836. The bank's formal name, according to section 9 of its charter as passed by Congress, was "The President, Directors, and Company, of the Bank of the United States". While other banks in the US were chartered by and only allowed to have branches in a single state, it was authorized to have branches in multiple states and lend money to the US government.

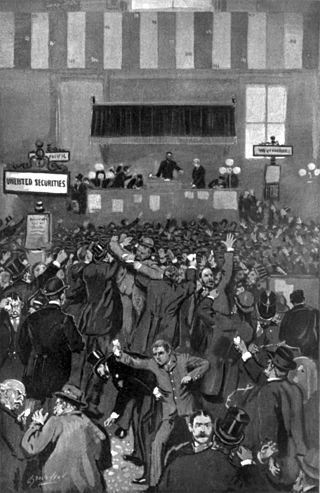

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the presidency of William McKinley.

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that began a major depression, which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages dropped, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment rose, and pessimism abounded.

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic heralded the transition of the nation from its colonial commercial status with Europe toward an independent economy.

Fractional-reserve banking is the system of banking in all countries worldwide, under which banks that take deposits from the public keep only part of their deposit liabilities in liquid assets as a reserve, typically lending the remainder to borrowers. Bank reserves are held as cash in the bank or as balances in the bank's account at the central bank. Fractional-reserve banking differs from the hypothetical alternative model, full-reserve banking, in which banks would keep all depositor funds on hand as reserves.

The Panic of 1857 was a financial crisis in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was the first financial crisis to spread rapidly throughout the United States. The world economy was more interconnected by the 1850s, which made the Panic of 1857 the first worldwide economic crisis. In Britain, the Palmerston government circumvented the requirements of the Bank Charter Act 1844, which required gold and silver reserves to back up the amount of money in circulation. Surfacing news of this circumvention set off the Panic in Britain.

This history of central banking in the United States encompasses various bank regulations, from early wildcat banking practices through the present Federal Reserve System.

Wildcat banking was the issuance of paper currency in the United States by poorly capitalized state-chartered banks. These wildcat banks existed alongside more stable state banks during the Free Banking Era from 1836 to 1865, when the country had no national banking system. States granted banking charters readily and applied regulations ineffectively, if at all. Bank closures and outright scams regularly occurred, leaving people with worthless money.

Pet banks is a derogatory term for state banks selected by the U.S. Department of Treasury to receive surplus Treasury funds in 1833. Pet banks are sometimes confused with wildcat banks. Although the two are distinct types of institutions that arose concomitantly, some pet banks were known to also engage in practices of wildcat banking. They were chosen among the big U.S. banks when President Andrew Jackson vetoed the recharter for the Second Bank of the United States, proposed by Henry Clay four years before the recharter was due. Clay intended to use the rechartering of the bank as a topic in the upcoming election of 1832. The charter for the Second Bank of the United States, which was headed by Nicholas Biddle, was for a period of twenty years beginning in 1816, but Jackson's distrust of the national banking system led to Biddle's proposal to recharter early, and the beginning of the Bank War. Jackson cited four reasons for vetoing the recharter, each degrading the Second Bank of the United States in claims of it holding an exorbitant amount of power. These reasons for vetoing the recharter were centered around Jackson's belief in his role as the representative of the common man. Amos Kendall, who was the intellectual driving force behind Jackson's 1832 election and Jackson himself, led Jackson to believe that the bank posed a political threat to Jackson. Kendall cautioned Jackson that unless he got rid of the Second Bank of the United States, it would find a way to elect its own candidate to the White House after Jackson was gone. Jackson saw the bank as a threat to the common man and "the great enemy of republicanism", and argued that as long as the national bank existed, the working class was constantly in danger of losing their stake in government.

The Independent Treasury was the system for managing the money supply of the United States federal government through the U.S. Treasury and its sub-treasuries, independently of the national banking and financial systems. It was created on August 6, 1846 by the 29th Congress, with the enactment of the Independent Treasury Act of 1846. It was expanded with the creation of the national banking system in 1863. It functioned until the early 20th century, when the Federal Reserve System replaced it. During this time, the Treasury took over an ever-larger number of functions of a central bank and the U.S. Treasury Department came to be the major force in the U.S. money market.

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shutdown of the Bank and its replacement by state banks.

Suffolk Bank was a private clearinghouse bank in Boston, Massachusetts, that exchanged specie or locally backed bank notes for notes from country banks to which city-dwellers could not easily travel to redeem notes. The bank was issued its corporate charter on February 10, 1818 by the 38th Massachusetts General Court to a group of the Boston Associates, and the charter's holders and bank's directors met periodically from February 27 to March 19 at the Boston Exchange Coffee House to discuss the organization of the bank. On April 1, 1818, the bank opened for business in rented offices on State Street until the bank moved permanently to the corner of State and Kilby Streets on April 17. In addition to Jackson and Parker, other prominent shareholders of the bank included William Appleton, Nathan Appleton, Timothy Bigelow, John Brooks, Gardiner Greene, Henry Hubbard, Augustine Heard, Amos Lawrence, Abbott Lawrence, Luther Lawrence, William Prescott, Dudley Leavitt Pickman, and Benjamin Seaver.

A Treasury Note is a type of short term debt instrument issued by the United States prior to the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913. Without the alternatives offered by a federal paper money or a central bank, the U.S. government relied on these instruments for funding during periods of financial stress such as the War of 1812, the Panic of 1837, and the American Civil War. While the Treasury Notes, as issued, were neither legal tender nor representative money, some issues were used as money in lieu of an official federal paper money. However the motivation behind their issuance was always funding federal expenditures rather than the provision of a circulating medium. These notes typically were hand-signed, of large denomination, of large dimension, bore interest, were payable to the order of the owner, and matured in no more than three years – though some issues lacked one or more of these properties. Often they were receivable at face value by the government in payment of taxes and for purchases of publicly owned land, and thus "might to some extent be regarded as paper money." On many issues the interest rate was chosen to make interest calculations particularly easy, paying either 1, 1+1⁄2, or 2 cents per day on a $100 note.

The Clearing House is a banking association and payments company owned by the largest commercial banks in the United States. The Clearing House is the parent organization of The Clearing House Payments Company L.L.C., which owns and operates core payments system infrastructure in the United States, including ACH, wire payments, check image clearing, and real-time payments through the RTP network, a modern real-time payment system for the U.S.

This article details the history of banking in the United States. Banking in the United States is regulated by both the federal and state governments.

Monetary policy in the United States is associated with interest rates and availability of credit.

The Safety Fund System was one of many banking systems created after the failure of the Second Bank of the United States and before a national banking system was established. Other notable systems include the Suffolk System, the free banking system, and the Forstall System. The Safety Fund System was the nation's first experiment in bank liability insurance. It was enacted by the New York legislature in 1829 and it began to fail following the Panic of 1837.

The Real Estate Bank of Arkansas was a bank in Arkansas during the 1830s through 1850s. Formed in 1836, the bank had a troubled history with accusations of waste and favoritism, as well as violations of the bank's legal charter. The bank suspended specie payments in 1839 to allow it to lend out more money. Paper money issued by the bank lost value, and the bank entered trusteeship in 1842. An act of the Arkansas legislature approved of the transfer to the trustees in 1843, but the trustees did not forward information to the state and personally benefited from the arrangement. In 1853, the Arkansas legislature passed a bill to have the Arkansas Attorney General take the bank to chancery court, but the filing could not be made until 1854 because of lack of cooperation from the trustees. April 1855 saw the bank's assets transferred from the trustees to the state, and in 1856 the first full public accounting of the bank's finances was made. The bonds related to the bank were not fully extinguished until 1894, and a portion of them, known as the Holford Bonds, proved particularly problematic.

Edmond Jean Forstall was an American banker, merchant, and planter, from New Orleans, Louisiana, from a prominent Louisiana Creole family through his mother, and Irish heritage on his father's side. He is known for developing The Forstall System in 1842.

References

Hammond, Bray. “Long and Short Term Credit in Early American Banking”. Quarterly Journal of Economics 49.1 (1934): 79–103.