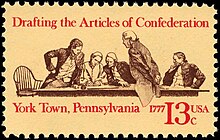

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 states of the United States, formerly the Thirteen Colonies, that served as the nation's first frame of government. It was debated by the Second Continental Congress at Independence Hall in Philadelphia between July 1776 and November 1777, and finalized by the Congress on November 15, 1777. It came into force on March 1, 1781, after being ratified by all 13 colonial states. A guiding principle of the Articles was the establishment and preservation of the independence and sovereignty of the states. The Articles consciously established a weak confederal government, affording it only those powers the former colonies had recognized as belonging to king and parliament. The document provided clearly written rules for how the states' league of friendship, known as the Perpetual Union, would be organized.

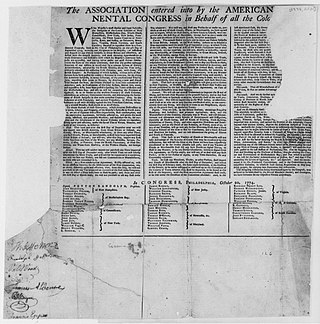

Richard Henry Lee was an American statesman and Founding Father from Virginia, best known for the June 1776 Lee Resolution, the motion in the Second Continental Congress calling for the colonies' independence from Great Britain leading to the United States Declaration of Independence, which he signed. Lee also served a one-year term as the president of the Continental Congress, proposed and was a signatory to the Continental Association, signed the Articles of Confederation, and was a United States Senator from Virginia from 1789 to 1792, serving part of that time as the second president pro tempore of the upper house.

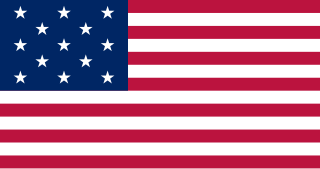

The Declaration of Independence, formally titled The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America in both the engrossed version and the original printing, is the founding document of the United States. On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress, who convened at Pennsylvania State House, later renamed Independence Hall, in the colonial era capital of Philadelphia. The 56 delegates who signed the Declaration of Independence came to be known as the nation's Founding Fathers.

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. The Continental Congress refers to both the First and Second Congresses of 1774–1781 and at the time, also described the Congress of the Confederation of 1781–1789. The Confederation Congress operated as the first federal government until being replaced following ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Until 1785, the Congress met predominantly at what is today Independence Hall in Philadelphia, though it was relocated temporarily on several occasions during the Revolutionary War and the fall of Philadelphia.

Samuel Huntington was a Founding Father of the United States and a lawyer, jurist, statesman, and Patriot in the American Revolution from Connecticut. As a delegate to the Continental Congress, he signed the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. He also served as President of the Continental Congress from 1779 to 1781, President of the United States in Congress Assembled in 1781, chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court from 1784 to 1785, and the 18th Governor of Connecticut from 1786 until his death. He was the first United States governor to have died while in office.

The history of the United States from 1776 to 1789 was marked by the nation's transition from the American Revolutionary War to the establishment of a novel constitutional order.

The Olive Branch Petition was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 5, 1775, and signed on July 8, 1775 in a final attempt to avoid war between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies in America. The Congress had already authorized the invasion of Canada more than a week earlier, but the petition affirmed American loyalty to Great Britain and entreated King George III to prevent further conflict. It was followed by the July 6, 1775 Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, however, which made its success unlikely in London. In August 1775, the colonies were formally declared to be in rebellion by the Proclamation of Rebellion, and the petition was rejected by the British government; King George had refused to read it before declaring the colonists traitors.

The Founding Fathers of the United States, often simply referred to as the Founding Fathers or the Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American revolutionary leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the War of Independence from Great Britain, established the United States of America, and crafted a framework of government for the new nation.

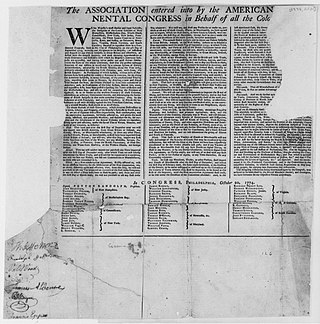

The Continental Association, also known as the Articles of Association or simply the Association, was an agreement among the American colonies adopted by the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia on October 20, 1774. It was a result of the escalating American Revolution and called for a trade boycott against British merchants by the colonies. Congress hoped that placing economic sanctions on British imports and exports would pressure Parliament into addressing the colonies' grievances, especially repealing the Intolerable Acts, which were strongly opposed by the colonies.

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates of 12 of the Thirteen Colonies held from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia at the beginning of the American Revolution. The meeting was organized by the delegates after the British Navy implemented a blockade of Boston Harbor and the Parliament of Great Britain passed the punitive Intolerable Acts in response to the Boston Tea Party.

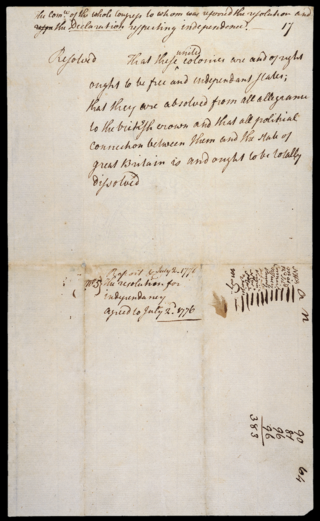

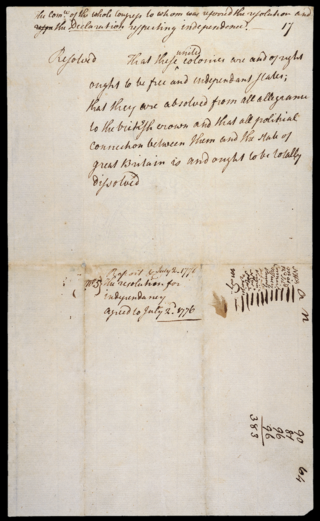

The Lee Resolution, also known as "The Resolution for Independence", was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2, 1776, resolving that the Thirteen Colonies were "free and independent States" and separate from the British Empire. This created what became the United States of America, and news of the act was published that evening in The Pennsylvania Evening Post and the following day in The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Declaration of Independence, which officially announced and explained the case for independence, was approved two days later, on July 4, 1776.

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States from March 1, 1781, until March 3, 1789, during the Confederation period. A unicameral body with legislative and executive function, it was composed of delegates appointed by the legislatures of the several states. Each state delegation had one vote. The Congress was created by the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union upon its ratification in 1781, formally replacing the Second Continental Congress.

Pennsylvania was the site of many key events associated with the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War. The city of Philadelphia, then capital of the Thirteen Colonies and the largest city in the colonies, was a gathering place for the Founding Fathers who discussed, debated, developed, and ultimately implemented many of the acts, including signing the Declaration of Independence, that inspired and launched the revolution and the quest for independence from the British Empire.

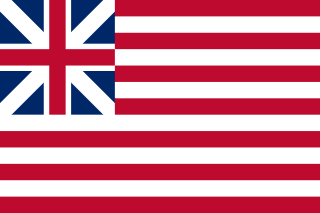

The United Colonies of North America was the official name as used by the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia for the newly formed proto-state comprising the Thirteen Colonies in 1775 and 1776, before and as independence was declared. Continental currency banknotes displayed the name 'The United Colonies' from May 1775 until February 1777, and the name was being used to refer to the colonies as a whole before the Second Congress met.

The Journals of the Continental Congress are official records from the first three representative bodies of the original United Colonies and ultimately the United States of America. The First Continental Congress was formed and met on September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, early in the American Revolution. Its purpose was to address "intolerable acts" and other infringements imposed on the colonies by the British Parliament. On October 20, 1774, it passed the Continental Association, and it ultimately formed the Second Continental Congress in May 1775 which, through 1781, was responsible for the Declaration of Independence and many critical articles establishing the United States of America. The Congress of the Confederation (1781–1789) immediately succeeded it after ratification of the Articles of Confederation and lasted through the end of the War for American Independence till 1789.

The New York Provincial Congress (1775–1777) was a revolutionary provisional government formed by colonists in 1775, during the American Revolution, as a pro-American alternative to the more conservative New York General Assembly, and as a replacement for the Committee of One Hundred. The Fourth Provincial Congress, resolving itself as the Convention of Representatives of the State of New York, adopted the first Constitution of the State of New York on April 20, 1777.

The Confederation period was the era of the United States' history in the 1780s after the American Revolution and prior to the ratification of the United States Constitution. In 1781, the United States ratified the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union and prevailed in the Battle of Yorktown, the last major land battle between British and American Continental forces in the American Revolutionary War. American independence was confirmed with the 1783 signing of the Treaty of Paris. The fledgling United States faced several challenges, many of which stemmed from the lack of an effective central government and unified political culture. The period ended in 1789 following the ratification of the United States Constitution, which established a new, more effective, federal government.

Then Province of Maryland had been a British / English colony since 1632, when Sir George Calvert, first Baron of Baltimore and Lord Baltimore (1579-1632), received a charter and grant from King Charles I of England and first created a haven for English Roman Catholics in the New World, with his son, Cecilius Calvert (1605-1675), the second Lord Baltimore equipping and sending over the first colonists to the Chesapeake Bay region in March 1634. The first signs of rebellion against the mother country occurred in 1765, when the tax collector Zachariah Hood was injured while landing at the second provincial capital of Annapolis docks, arguably the first violent resistance to British taxation in the colonies. After a decade of bitter argument and internal discord, Maryland declared itself a sovereign state in 1776. The province was one of the Thirteen Colonies of British America to declare independence from Great Britain and joined the others in signing a collective Declaration of Independence that summer in the Second Continental Congress in nearby Philadelphia. Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton signed on Maryland's behalf.

The Augusta Declaration, or the Memorial of Augusta County Committee, May 10, 1776, was a statement presented to the Fifth Virginia Convention in Williamsburg, Virginia on May 10, 1776. The Declaration announced the necessity of the Thirteen Colonies to form a permanent and independent union of states and national government separate from Great Britain, with whom the Colonies were at war.