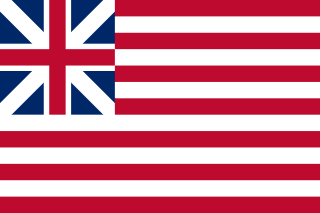

The American Revolution was a rebellion and political movement in the Thirteen Colonies which peaked when colonists initiated an ultimately successful war for independence against the Kingdom of Great Britain. Leaders of the American Revolution were colonial separatist leaders who originally sought more autonomy within the British political system as British subjects, but later assembled to support the Revolutionary War, which successfully ended British colonial rule over the colonies, establishing their independence, and leading to the creation of the United States of America.

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. The Continental Congress refers to both the First and Second Congresses of 1774–1781 and at the time, also described the Congress of the Confederation of 1781–1789. The Confederation Congress operated as the first federal government until being replaced following ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Until 1785, the Congress met predominantly at what is today Independence Hall in Philadelphia, though it was relocated temporarily on several occasions during the Revolutionary War and the fall of Philadelphia.

Silas Deane was an American merchant, politician, and diplomat, and a supporter of American independence. Deane served as a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, and then became the first foreign diplomat from the United States to France, where he helped negotiate the 1778 Treaty of Alliance that allied France with the United States during the American Revolutionary War.

Joseph Hewes was an American Founding Father and a signer of the Continental Association and U.S. Declaration of Independence. Hewes was a native of Princeton, New Jersey, where he was born in 1730. His parents were members of the Society of Friends, commonly known as Quakers. Early biographies of Hewes falsely claim that his parents came from Connecticut. Hewes may have attended the College of New Jersey, known today as Princeton University but there is no record of his attendance. He did, in all probability, attend the grammar school set up by the Stonybrook Quaker Meeting near Princeton.

The Intolerable Acts, sometimes referred to as the Insufferable Acts or Coercive Acts, were a series of five punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure enacted by Parliament in May 1773. In Great Britain, these laws were referred to as the Coercive Acts. They were a key development leading to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in April 1775.

The Second Continental Congress was the late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and the Revolutionary War, which established American independence from the British Empire. The Congress constituted a new federation that it first named the United Colonies, and in 1776, renamed the United States of America. The Congress began convening in Philadelphia, on May 10, 1775, with representatives from 12 of the 13 colonies, after the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

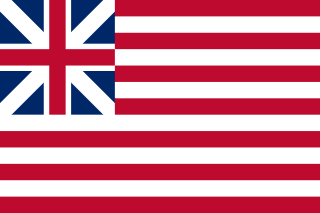

The Continental Association, also known as the Articles of Association or simply the Association, was an agreement among the American colonies adopted by the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia on October 20, 1774. It was a result of the escalating American Revolution and called for a trade boycott against British merchants by the colonies. Congress hoped that placing economic sanctions on British imports and exports would pressure Parliament into addressing the colonies' grievances, especially repealing the Intolerable Acts, which were strongly opposed by the colonies.

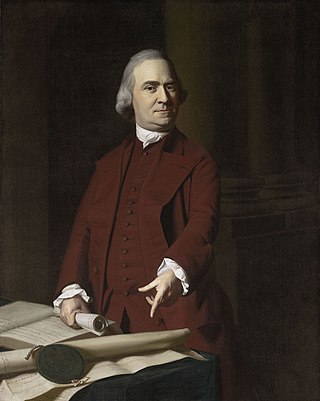

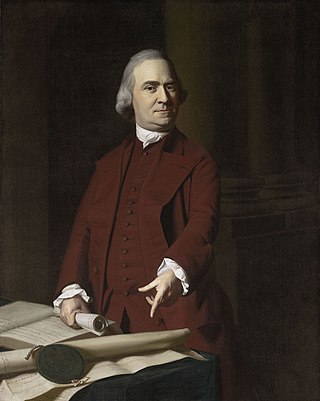

The committees of correspondence were a collection of American political organizations that sought to coordinate opposition to British Parliament and, later, support for American independence during the American Revolution. The brainchild of Samuel Adams, a Patriot from Boston, the committees sought to establish, through the writing of letters, an underground network of communication among Patriot leaders in the Thirteen Colonies. The committees were instrumental in setting up the First Continental Congress, which convened in Philadelphia in September and October 1774.

The Suffolk Resolves was a declaration made on September 9, 1774, by the leaders of Suffolk County, Massachusetts. The declaration rejected the Massachusetts Government Act and resulted in a boycott of imported goods from Britain unless the Intolerable Acts were repealed. The Resolves were recognized by statesman Edmund Burke as a major development in colonial animosity leading to adoption of the United States Declaration of Independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1776, and he urged British conciliation with the American colonies, to little effect. The First Continental Congress endorsed the Resolves on September 17, 1774, and passed the similarly themed Continental Association on October 20, 1774.

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates of 12 of the Thirteen Colonies held from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia at the beginning of the American Revolution. The meeting was organized by the delegates after the British Navy implemented a blockade of Boston Harbor and the Parliament of Great Britain passed the punitive Intolerable Acts in response to the Boston Tea Party.

William Montgomery was a colonial-American patriot, pioneer, soldier, public servant, and abolitionist.

The United Colonies was the name used by the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia to describe the proto-state comprising the Thirteen Colonies in 1775 and 1776, before and as independence was declared. Continental currency banknotes displayed the name 'The United Colonies' from May 1775 until February 1777, and the name was being used as a colloquial phrase to refer to the colonies as a whole before the Second Congress met, although the precise place or date of its origin is unknown.

The Committee of Sixty or Committee of Observation was a committee of inspection formed in the City and County of New York, in 1775, by rebels to enforce the Continental Association, a boycott of British goods enacted by the First Continental Congress. It was the successor to the Committee of Fifty-one, which had originally called for the Congress to be held, and was replaced by the Committee of One Hundred.

The New York Provincial Congress (1775–1777) was a revolutionary provisional government formed by colonists in 1775, during the American Revolution, as a pro-American alternative to the more conservative New York General Assembly, and as a replacement for the Committee of One Hundred. The Fourth Provincial Congress, resolving itself as the Convention of Representatives of the State of New York, adopted the first Constitution of the State of New York on April 20, 1777.

The Lexington Alarm announced, throughout the American Colonies, that the Revolutionary War began with the Battle of Lexington and the Siege of Boston on April 19, 1775. The goal was to rally patriots at a grass roots level to fight against the British Redcoats and support the minutemen of the Massachusetts militia.

The Provincial Congresses were extra-legal legislative bodies established in ten of the Thirteen Colonies early in the American Revolution. Some were referred to as congresses while others used different terms for a similar type body. These bodies were generally renamed or replaced with other bodies when the provinces declared themselves states.

Samuel Adams was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and other founding documents, and one of the architects of the principles of American republicanism that shaped the political culture of the United States. He was a second cousin to his fellow Founding Father, President John Adams.

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress (1774–1780) was a provisional government created in the Province of Massachusetts Bay early in the American Revolution. Based on the terms of the colonial charter, it exercised de facto control over the rebellious portions of the province, and after the British withdrawal from Boston in March 1776, the entire province. When Massachusetts Bay declared its independence in 1776, the Congress continued to govern under this arrangement for several years. Increasing calls for constitutional change led to a failed proposal for a constitution produced by the Congress in 1778, and then a successful constitutional convention that produced a constitution for the state in 1780. The Provincial Congress came to an end with elections in October 1780.

The Augusta Declaration, or the Memorial of Augusta County Committee, May 10, 1776, was a statement presented to the Fifth Virginia Convention in Williamsburg, Virginia on May 10, 1776. The Declaration announced the necessity of the Thirteen Colonies to form a permanent and independent union of states and national government separate from Great Britain, with whom the Colonies were at war.

Tory Act of 1776 was penned as seven resolutions passed by the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on January 2, 1776. The legislative resolutions emphasized the American Patriots opposing sentiments towards the colonial political factions, better known as British America's Tories or Royalists.