The American Revolutionary War, also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was an armed conflict that was part of the broader American Revolution, in which American Patriot forces organized as the Continental Army and commanded by George Washington defeated the British Army. The conflict was fought in North America, the Caribbean, and the Atlantic Ocean. The war ended with the Treaty of Paris (1783), which resulted in Great Britain ultimately recognizing the independence of the United States of America.

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was an ideological and political movement in the Thirteen Colonies which peaked when colonists initiated the ultimately successful war for independence against the Kingdom of Great Britain. Leaders of the American Revolution were colonial separatist leaders who originally sought more autonomy as British subjects, but later assembled to support the Revolutionary War, which ended British colonial rule over the colonies, establishing their independence as the United States of America in July 1776.

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. The Continental Congress refers to both the First and Second Congresses of 1774–1781 and at the time, also described the Congress of the Confederation of 1781–1789. The Confederation Congress operated as the first federal government until being replaced following ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Until 1785, the Congress met predominantly at what is today Independence Hall in Philadelphia, though it was relocated temporarily on several occasions during the Revolutionary War and the fall of Philadelphia.

Silas Deane was an American merchant, politician, and diplomat, and a supporter of American independence. Deane served as a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, and then became the first foreign diplomat from the United States to France, where he helped negotiate the 1778 Treaty of Alliance that allied France with the United States during the American Revolutionary War.

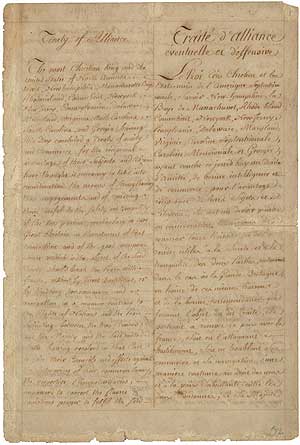

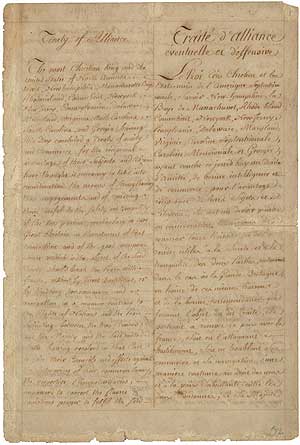

The Treaty of Alliance, also known as the Franco-American Treaty, was a defensive alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States formed amid the American Revolutionary War with Great Britain. It was signed by delegates of King Louis XVI and the Second Continental Congress in Paris on February 6, 1778, along with the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and a secret clause providing for the entry of other European allies; together these instruments are sometimes known as the Franco-American Alliance or the Treaties of Alliance. The agreements marked the official entry of the United States on the world stage, and formalized French recognition and support of U.S. independence that was to be decisive in America's victory.

The Continental Navy was the navy of the Thirteen Colonies during the American Revolutionary War. Founded on October 13, 1775, the fleet developed into a substantial force throughout the Revolutionary War, owing partially to the efforts of naval patrons within the Continental Congress. These congressional patrons included the likes of John Adams, who served as the chairman of the Naval Committee until 1776, when Commodore Esek Hopkins received instruction from the Continental Congress to assume command of the force.

Arthur Lee was an American physician, diplomat and abolitionist who was born in the British colony of Virginia. He helped negotiate and signed the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France, along with Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane, which allied France and the United States in fighting the war.

During the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Army and British Army conducted espionage operations against one another to collect military intelligence to inform military operations. In addition, both sides conducted political action, covert action, counterintelligence, deception, and propaganda operations as part of their overall strategies.

John Fell (1721–1798) was an American merchant and jurist. Born in New York City, he was engaged in overseas trade and had acquired a small fleet of ships by the time he moved to Bergen County, New Jersey, in the 1760s, and lived at "Peterfield", a home in present-day Allendale, New Jersey that has become known as the "John Fell House". He served as judge of the court of common pleas in Bergen County from 1766 to 1774. With the coming of the American Revolutionary War, he became chairman of Bergen County's committee of correspondence and the committee of safety. He was Bergen County's leading delegate to the Provincial Congress of New Jersey in 1775. In 1776 Fell was elected to a one-year term in the New Jersey Legislative Council representing Bergen County.

Liberty! The American Revolution is a six-hour documentary miniseries about the Revolutionary War, and the instigating factors, that brought about the United States' independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain. It was first broadcast on the Public Broadcasting Service in 1997.

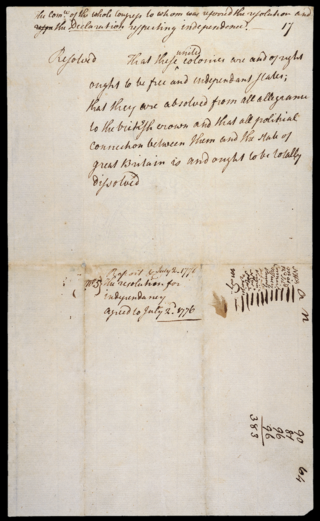

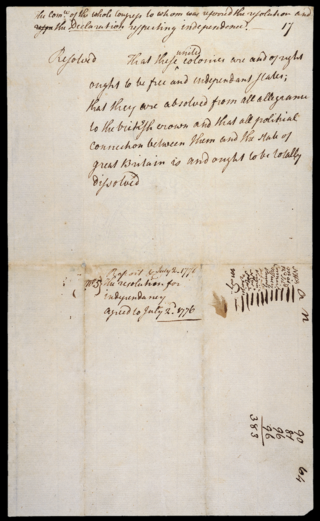

The Lee Resolution, also known as "The Resolution for Independence", was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2, 1776, resolving that the Thirteen Colonies were "free and independent States" and separate from the British Empire. This created what became the United States of America, and news of the act was published that evening in The Pennsylvania Evening Post and the following day in The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Declaration of Independence, which officially announced and explained the case for independence, was approved two days later, on July 4, 1776.

French involvement in the American Revolutionary War of 1775–1783 began in 1776 when the Kingdom of France secretly shipped supplies to the Continental Army of the Thirteen Colonies upon its establishment in June 1775. France was a long-term historical rival with the Kingdom of Great Britain, from which the Colonies were attempting to separate.

The Model Treaty, or the Plan of 1776, was a template for commercial treaties that the United States planned to make with foreign powers during the American Revolution against Great Britain. It was drafted by the Continental Congress to secure economic resources for the war effort, and to serve as an idealistic guide for future relations and treaties between the new American government and other nations. The Model Treaty thus marked the revolution's turning point towards seeking independence, and is subsequently considered a milestone in U.S. foreign relations.

The Treaty of Amity and Commerce established formal diplomatic and commercial relations between the United States and France during the American Revolutionary War. It was signed on February 6, 1778 in Paris, together with its sister agreement, the Treaty of Alliance, and a separate, secret clause allowing Spain and other European nations to join the alliance. These were the first treaties negotiated by the fledgling United States, and the resulting alliance proved pivotal to American victory in the war; the agreements are sometimes collectively known as the Franco-American Alliance or the Treaties of Alliance.

Charles William Frédéric Dumas (1721–1796) was a man of letters living in the Dutch Republic who served as an American diplomat during the American Revolution.

The Special Expedition was an expeditionary force deployed by France to North America to support the United States against Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. Arriving on 11 July 1780 under the leadership of the Comte de Rochambeau, it numbered up to 5,500 troops and played a decisive role in the final battles of the war.

Diplomacy was central to the outcome of the American Revolutionary War and the broader American Revolution. Before the outbreak of armed conflict in April 1775, the Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain had initially sought to resolve their disputes peacefully from within the British political system. Once open hostilities began, the war developed an international dimension, as both sides engaged in foreign diplomacy to further their goals, while governments and nations worldwide took interest in the geopolitical and ideological implications of the conflict.

The Franco-American alliance was the 1778 alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States during the American Revolutionary War. Formalized in the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, it was a military pact in which the French provided many supplies for the Americans. The Netherlands and Spain later joined as allies of France; Britain had no European allies. The French alliance was possible once the Americans captured a British invasion army at Saratoga in October 1777, demonstrating the viability of the American cause. The alliance became controversial after 1793 when Great Britain and Revolutionary France again went to war and the U.S. declared itself neutral. Relations between France and the United States worsened as the latter became closer to Britain in the Jay Treaty of 1795, leading to an undeclared Quasi War. The alliance was defunct by 1794 and formally ended in 1800.

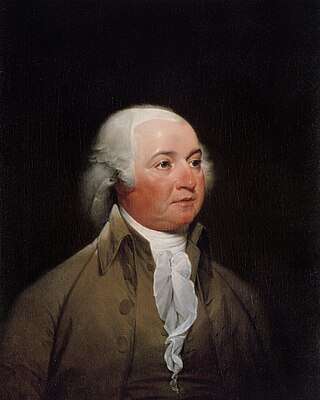

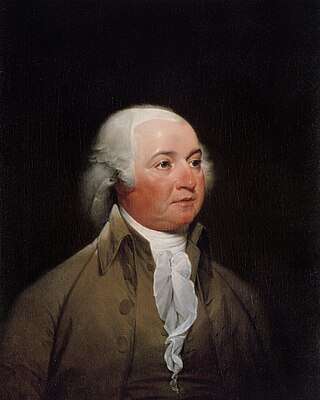

John Adams (1735–1826) was an American Founding Father who served as one of the most important diplomats on behalf of the new United States during the American Revolution. He served as minister to the Kingdom of France and the Dutch Republic and then helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris to end the American Revolutionary War.

The Papers of Benjamin Franklin is a collaborative effort by a team of scholars at Yale University, American Philosophical Society and others who have searched, collected, edited, and published the numerous letters from and to Benjamin Franklin, and other works, especially those involved with the American Revolutionary period and thereafter. The publication of Franklin's papers has been an ongoing production since its first issue in 1959, and is expected to reach nearly fifty volumes, with more than forty volumes completed as of 2022. The costly project was made possible from donations by the American Philosophical Association and Life magazine.