Accomplishments and legacy

African Free School

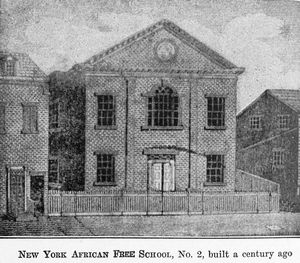

In 1787, the Society founded the African Free School in Williamsburgh, predating its consolidation into Brooklyn. [7] No schools in New York City were open to Black people. Brooklyn was still separate from New York at the time, and in 1815, a resident of the village of Brooklyn opened the first private school for black students at his home in the neighborhood of DUMBO. Peter Croger, a free black man, advertised an “African School” would be open during the day and evening for “those who wish [to] be taught the common branches of education.” [8] Eventually several other schools in other points in Brooklyn were established; African Free School No. 2 in 1839; also Colored School No. 3. [9] [10] [11]

Litigation

The New York courts and law enforcement zealously enforced the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. Attempts by the Society to dispute the status or ownership of the detained "fugitives" met with little success. [12] In 1801, under a New York law that prohibited the transportation of slaves through the state, the Society sought to prevent a slave-holding household from disembarking on a sloop for Virginia. However, after city wardens broke up a free-black crowd outside the household's residence, in what press reported as a riot, the Society failed to pursue the freedom suit. [13]

Greater success attended the Society in the courts after it was joined and represented by two exiled United Irishmen, newly admitted to the New York bar, Thomas Addis Emmet and William Sampson. In 1805, in the Topham case, Emmet secured victory for the Society under the federal Slave Trade Act of 1794. He obtained a writ forbidding departure of a ship bound for Africa laden with cargo of rum and other spirits intended for the purchase of slaves. [12] [14] Further success attended proceedings in 1806 to prevent a sloop leaving for the south with three free blacks on board, who had been seized to be sold as enslaved. [15]

In The Commissioners of the Almshouse v Alexander Whistelo (1808), involving a black man in a case of paternity, William Sampson, defended the integrity of "interracial" marriage, arguing that ‘‘every man must follow his own pleasure . . . neither philosophy nor religion have forbade such mixtures.’’ [16] In Amos and Demis Broad (1809), Sampson succeeded in having a sadistically abused mother and her 3-year-old daughter, manumitted. [17] Sampson had nonetheless to lament that the law kept the woman from testifying on her own behalf: "the silence which fate, for I will not call it law, imposes on the slave who cannot tell us of his own complaint; gagged, and reduced to a state of a dumb brute . . . [is a] weighty obstacle to justice". [18]

Emmet continued to represent the Society, and to defend African Americans against the claims of their former masters, until 1827. [12]

Legislation

Beginning in 1785, the Society lobbied for a state law to abolish slavery in the state, as all the other northern states (except New Jersey) had done. Considerable opposition came from the Dutch areas upstate (where slavery was still popular), [19] as well as from the many businessmen in New York who profited from the slave trade. The two houses passed different emancipation bills and could not reconcile them. Every member of the New York legislature but one voted for some form of gradual emancipation, but no agreement could be reached on the civil rights of freedmen afterwards.[ citation needed ]

Some measure of success finally came in 1799 [20] [ page needed ] when John Jay, as Governor of New York State, signed the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery into law; however it still ignored the subject of civil rights[ which? ] for freed slaves. [20] [ page needed ] [21] [ full citation needed ] The resulting legislation declared that, from July 4 of that year, all children born to slave parents would be free. It also outlawed the exportation of current slaves to other states. However, the Act held the caveat that the children would be subject to apprenticeship. These same children would be required to serve their mother's owner until age twenty-eight for males, and age twenty-five for females. The law defined the children of slaves as a type of indentured servant, while scheduling them for eventual freedom. [20] [ page needed ]

Another law was passed in 1817:

Whereas by a law of this State, passed the 31st of March, 1817, all slaves born between the 4th of July, 1799, and the 31st of March, 1817 shall become free, the males at 28, and females at 25 years old, and all slaves born after the 31st of March, 1817, shall be free at 21 years old, and also all slaves born before the 4th day of July, 1799 shall be free on the 4th day of July, 1827 [22]

The last slaves in New York were emancipated by July 4, 1827; the process was the largest emancipation in North America before 1861. [23] Although the law as written did not set free those born between 1799 and 1817, many still children, public sentiment in New York had changed between 1817 and 1827, enough so that in practice they were set free as well. The press referred to it as a "General Emancipation". An estimated 10,000 enslaved New Yorkers were freed in 1827. [24]

Thousands of freedmen celebrated with a parade in New York. The parade was deliberately held on July 5, not the 4th. [25]